In my Grandmother’s House

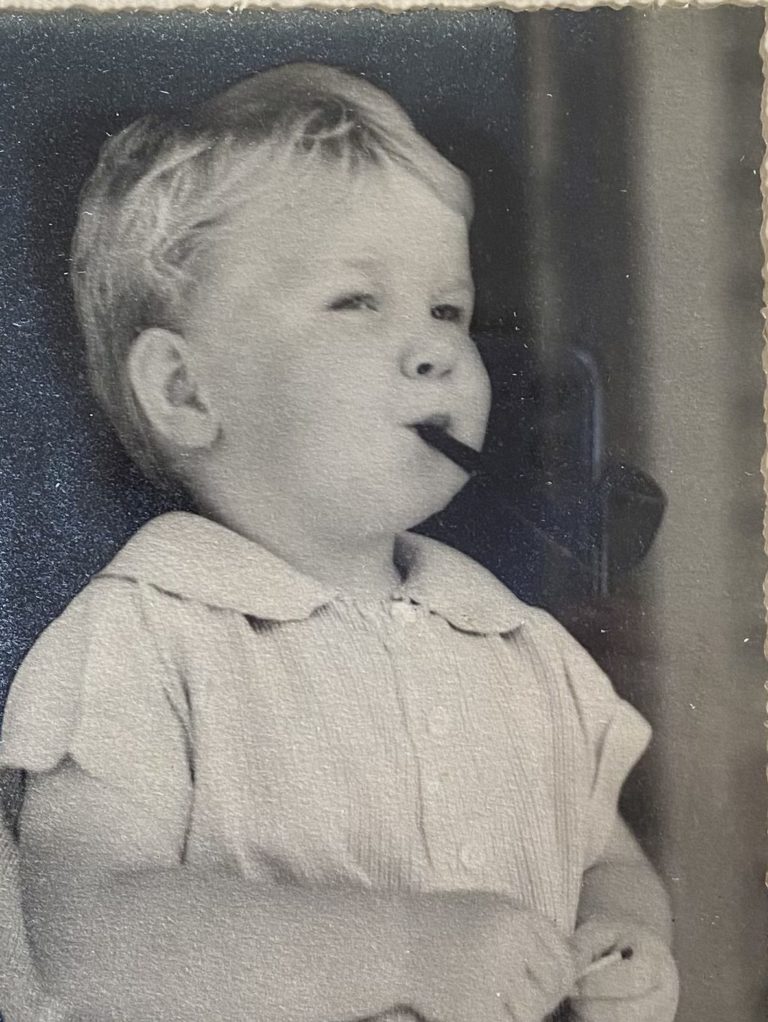

As a child I spent a considerable amount of time in my grandmother’s house in St Albans. It was a short walk from our own house on Cranford Street in Christchurch, a distance which I could comfortably cover on foot or on my trike. My mother had chosen this closeness deliberately. She liked a social life and at that time was enthusiastic about horses, keeping one at a stable in Brighton, so it was useful to be able to leave me with her mother, sometimes overnight when she was pony-trekking.

I loved the house. It was a generously-proportioned single-storey house in Bishop Street which my grandparents had built in 1910 and was distinctly old-fashioned by my time in the 1940s. It was controlled and run by my grandmother, Alice, and her unmarried sister, Edith Marlowe. My grandfather, John Vincent, was a marine engineer who had a business in Lyttelton and went there every day. In his absence and indeed in his presence the two sisters presided and gave the household its rhythm. Everything moved to the gentle beat of a seasonal drum. There were days for drying lavender for the bed linen, spreading walnuts on newspaper to dry on the deep verandah, making preserves or soap and buying pullets for the henhouse . The house rotated around the seasons like the church around the liturgical year with rituals like shelling the peas or picking the raspberries making their appearance with reassuring predictability.

The house was spacious but not grand, with the practicality to be expected from an engineer. At the back there was a washhouse, lavatory (with a stern notice dated 1908 not to put rags in it), and a space always referred to as the “bike room”. Inside the back door was a scullery, pantry and quite a small kitchen, all of which opened on to the “breakfast room” where I spent most of my day.

The washhouse always seemed rather gloomy, though it had a window looking across the lawn and quince tree. Inside were two kauri washtubs, a mangle and a large bricked-in copper. It was deserted most days of the week which possibly added to the gloom. It sprang to energetic life on washdays, Monday I think. Then the copper (deriving its name from the gleaming copper bowl cemented into the top) was filled with water and firewood was pushed into the grate underneath. When the water was boiling in large, fascinating bubbles the household linen was tipped in along with a cake of homemade soap and as they bubbled away the churning clothes from time to time were plunged down with a wooden pole. The room filled with steam and preoccupied women, scrubbing in the tubs, running sheets through the mangle or taking baskets of wet clothes out to dry on the lines which ran past the woodshed. On a sound instinct I usually kept away.

The scullery just inside the back door had lost much of its purpose with the wartime disappearance of domestic help. Apart from two sinks its only occasional interest for me was a ponderous disc which made a satisfying rumble when rotated with a handle. Its purpose – cleaning stained table-knives – had also vanished with the coming of stainless steel.

The pantry was more fun. It was a dark cave of shelves laden with jams and jellies, preserves, bottled fruit, pickled walnuts and other produce from the garden. As a wedding present my grandmother had been given a munificent volume of printed labels for jam. By my time the common labels like raspberry and apricot had long since been used but the other labels with their flowing writing wreathed in gold were too attractive to be discarded. Over the years the labels of the everyday jams grew more and more eccentric. A code evolved, known only to my grandmother and her sister. Whenever I was sent to the pantry to get another jar of raspberry jam I would be directed this year to look for a crab-apple and ginger or medlar jelly label.

My life revolved around the breakfast room as indeed did the morning life of the whole house. It may have been different before the war, that mysterious phrase with which I grew up and which became in the ears of wartime children a golden Hesperides where everything was possible and, even better, available. I looked with longing at the advertisements for Hornby trains and Meccano sets on the backs of tattered pre-war magazines. On the platform for those waiting for a train there was an ancient machine which “before the war” had dispensed tuppenny bars of chocolate. I tried it hopefully every time I was there, fascinated that in those golden times chocolate could be acquired even on Christchurch railway station.

Before the war there was a maid and a gardener to help run a household which was in some ways the equivalent of a modest-sized business. The only relic of these was the story, repeated on family occasions, of the maid Nancy who used to chase me with a fish slice. This amused everyone except me who had always felt that being chased by a hefty red-faced woman with a weapon was an over-rated pleasure. The absence of pre-war help, however, did not seem to bother the two sisters who bustled about in and out of the breakfast room on their morning tasks, keeping up a brisk conversation. My grandmother Alice was called “Al” by her sister which all my childhood I thought was “Owl”.

Her sister’s name had progressed by a natural evolution from Aunt Edie to Deedie by which she was known to everyone in the family for the rest of her life. When she had completed one task her habit was to say “Now-ee” as she considered the next. She was unmarried, her prospective husband having gone to the Boer War and never come back. This sadness had long been covered by time, she and her sister ran the house together without a cross word that I ever heard and she was the beloved Deedie to a growing crowd of children.

Half-way through their work there was a pause for morning tea, with an Anzac biscuit or Afghan (both still on New Zealand shelves) for me. The sisters sat down in armchairs while one scanned the Press newspaper, occasionally reading out interesting snippets to the other. The paper had traditionally been brought in by the dog but this had to be discontinued after the dog began to bring other peoples’ copies as well. After twenty minutes or so of rest the ladies went back to work, baking, cleaning and polishing.

The breakfast room had a fireplace with usually a wood fire and, hanging above it, a Burne-Jones reproduction which I disliked. A large sash-window looked out into the garden and stream. Alongside one wall was the breakfast table with eight chairs dating from my grandparent’s wedding in 1898 on which I had my meals, swinging my legs too short for the floor and if I was lucky eating the pikelets and quince jelly which was my special pleasure. On the adjoining wall was another relic of my grandparent’s marriage, a little couch which had come down in the world from the drawing-room to house my grandfather’s terrier Winkie and sometimes me. I still have it, and two of the breakfast table chairs, touchingly made of kauri stained to look like mahogany.

Beyond the breakfast room a wide hallway ran down the length of the house, off which opened bedrooms and bathroom and on the other side the long dining-room with an equally long kauri dining table where dinner was eaten after my grandfather had returned. On great occasions, like my grandparents’ wedding anniversary, I enjoyed turning the handle which opened the table to its impressive length, adding three or four leaves. Dinners were a formal business, with everyone seated around the table while a succession of dishes was passed through a hatch from the breakfast room. When old enough, I was hoisted on to a dining chair and sat there picking at my food and listening to the talk.

The hallway had no windows and tended to be rather dark, especially at the far end where the “hoover” was stowed. It was coiled around its suction tube which was black with white spots and looked alarmingly like a snake in wait. So trips down the hall had to be executed at speed and perhaps a leap at the end to avoid this predatory reptile. Then you had reached the telephone. A brown wooden box on the wall with a mouthpiece in the middle and an earpiece on a cord. There was a handle which you turned briskly to ring out. For an incoming call you fixed the earpiece in place and said “Are you there?” firmly to the caller. This has caused mirth to later generations but it was a necessary step. Sometimes when the greeting was given you weren’t there at all and the whole process had to be repeated.

On rare and exciting occasions a long-distance call was attempted. This involved making a booking hours and sometimes days ahead. A rather snooty person from the Post Office would then ring to tell you to standby later in the day. Then at the appointed time the phone would ring and there would be Great-Uncle Jim in Dunedin, sounding as if he was still in a rather crackly Dunedin.

The phone was in the hall proper which boasted the front door, a long sideboard for coats and sometimes presents, and uncomfortable hall chairs with green-tiled backs on which no-one was ever known to sit. Off the hall were my grandparents and great-aunt Edie’s bedrooms and the drawing-room, normally secluded and certainly not for the use of children. It was a handsome room with glass-fronted bookcases (Dickens a specialty), a large bay window looking across the garden to the street and an equally large fireplace with an huge fur hearthrug, kangaroo or wallaby, in which I enjoyed rolling.

The room was rarely used and dwelt in dignified solitude with the door closed. This aloofness extended to being locked on Christmas Day. After dinner it would be unlocked and all the children streamed down the hallway into the drawing-room, to find that Father Christmas had thoughtfully arranged everyone’s presents on the hearth. On other days it would be pressed into service for afternoon card parties. My grandmother and her friends sat at one or two card tables playing sometimes whist but more often cribbage (“crib”)while I sat on the window seat, listening to their gossip and waiting for afternoon tea.

At night I normally occupied the smallest bedroom, always called “Jack’s room” after my uncle. It had a bookshelf above it with some nifty adventure stories which my uncle had acquired and which I enjoyed reading. Sometimes, when I was not well, I enjoyed an even greater adventure. A bed would be made up in the drawing-room beside the fire and I would fall asleep in this unfamiliar room to the ticking of the eight-day clock, waking drowsily from time to time to the comforting sight of the firelight flickering on the ceiling.

The bustle of the morning changed after lunch as did the two sisters who retired to put on their “afternoon dresses”, suitable for receiving calls or going out. Friends arrived for card parties or simply afternoon tea, or visits were made to the shops at the end of Colombo Street and the library for books they or my grandfather might like. Occasionally they took the “car” (never called a tram) to visit one of the department stores in the city. Neither of them had ever considered driving.

In the evening my grandfather returned from Lyttelton and the house’s afternoon tranquillity disappeared in the flurry of his arrival and the preparation of dinner. There were no drinks beforehand. On hot days my grandmother would sometimes take what she genteelly called a glass of “ale”. My grandfather also drank rarely, confining himself to a splash of rum in his after-dinner tea in memory of his sea-going days. Decanters of sherry and madeira stood on the sideboard, surreptitiously tasted by me, but they were offered only to distinguished visitors, the madeira always with a slice of my great-aunt’s superb fruitcake. After dinner two or three grown-ups might offer to play crib with me. It was a game within my reach and I loved the scoring cries of “Fifteen two and the rest won’t do” or “Fifteen four and the rest won’t score”. This charted the uncertain progress of my peg along the crib board until, if fortune smiled, I might “peg out”. Otherwise people sat by the dining-room fire and talked or read. My grandfather would often doze off and recall his loathing of the defunct Liberal Party, waking with an involuntary snort of “Rascals!” to which my grandmother would respond with a warning “Now John”.

Part II

The house stood on one side of more than two acres of land which sloped down to a stream (always termed the “creek”) and rose up the other side to a back section of half an acre. The flower garden had the usual beds of annuals and shrubs in which my grandmother worked assiduously but to a child’s eye there was little that was memorable except an old weeping elm on the front lawn. It had a curtain of leaves reaching down to the ground, enclosing a magical circle in which you could not so much hide (everyone knew where it was) as enjoy a sort of desert-island solitariness.

The real pleasure for a child lay in the extensive grounds behind the house. Past the big walnut tree growing outside the breakfast room window, past the path lined with lavender that led down to the creek, there were vegetable beds and two fowl houses where I might be delegated to feed the chooks and shut them in for the night. Best of all, though, was what had become a rather overgrown orchard, with Cox’s Orange apple trees, nectarine, peach and pear trees from which in the summer a peckish child could always glean something to eat.

Across the stream was the back section which had been orphaned by the departure of a gardener and was largely abandoned except by children. Except for being rather obvious, it was perfect for hide-and-seek, with two half-ruined sheds surrounded by long summer grass and anonymous bushes. Along one side was a row of gooseberry bushes beside which we squatted and gorged on the fat, sweet berries (“goosegogs” in our language). In the middle was an oblong plot of raspberries which, though entirely neglected, went on producing raspberries seemingly by force of habit.

An ominous chopping block stood just outside the back door where a regular success of hens were beheaded. Birds were a staple of the household diet. I admired the slightly sinister gleam of my grandfather’s English shotgun and my uncles were dedicated hunters who were always dropping in with braces of ducks and every form of edible wildlife from venison to rabbits. To my discomfort a hare turned up and was duly jugged by the sisters in an ancient utensil which had been kept for this moment. More acceptable was the swan’s egg which was baked into a sponge-cake of a strikingly yellow colour, but I did not much like that either.

I had an instinctive dislike of experimenting with food and was no great eater of any meat. I would sit at the table, gloomily contemplating my lamb, having convinced myself that it was really snake, until my tolerant grandmother or her sister would quietly remove the dish and replace it with something more agreeable, stewed fruit perhaps or scones with jam. Ice-cream was unknown at meals except for its contribution to the stupendous excitement of Christmas Day when in the morning we drove down to the Perfection ice-cream plant on Manchester Street and took delivery of a round of ice-cream the size of a Stilton cheese and brought it home trailing triumphant clouds of dry ice.

There were two garages on opposite sides of the street frontage, each just large enough to hold a car. The one beside the gate used by everyone except visitors held my grandfather’s splendid 1916 Buick, a cream-coloured vehicle with a windscreen that stood boldly upright and a gleaming canvas hood. I never saw it on the road; it had been laid up at least since the outbreak of the war and perhaps earlier, though I remember box-brownie photos of ladies in duster dresses and veils sitting in it. It just fitted in the garage and sat in it with the resigned air of an exiled duke, accompanied only by a faded wooden sign that said ‘Fortrose’, the farm in South Otago that my grandfather had been exiled from when his father died in the 1880s.

Along the street the other garage was busier. It held my Aunt Mona’s bull-nosed Morris in which, to the extent permitted by petrol rationing, we would sometimes go on a picnic. The ladies were great picnickers and the boot would be packed with tartan rugs, cups and plates, baskets of food and the patent billy for boiling the tea. When the well-loaded car set off we were always required by my aunt to sing a rousing chorus “There’ll Always Be An England” since, until June 1941, this seemed by no means assured.

The car would stop at a pleasant spot along the Hurunui or Ashley rivers or inland in the foothills around Methven or Oxford and the rugs would be spread out on the grass. Then there was a brisk search for twigs to fire up the billy, which required small sticks in an opening in the base and water in the top. Once this had boiled and the ticklish task managed of getting it into a teapot, everyone dived into the baskets of egg sandwiches, scones and pikelets until a comfortable silence fell. We often picnicked near the side of the road but there was little inconvenience from traffic passing on the unsealed back-country roads, only the occasional drover and his sheep. The young dogs ran back and forth, with their tongues lolling in the summer heat, while a shrewd older dog paced along restfully in the shade under the drover’s cart. Then we drove home, uneventfully except for the long-remembered time when I threw up.

The gate beside my aunt’s garage, though unmarked, was the official entrance for all visitors except the family. It ran along a path above the stream, then over a wrought-iron bridge up to the front door. It was forever fixed in my memory one Christmas morning when I was called to the front verandah to see Father Christmas himself, in a blaze of red below a flowing white beard and white-bobbled nightcap striding along the path with a bulging sack over his shoulder. On the verandah he dispensed gifts from the sack without even waiting to go down the chimney. I was so awed to shake hands with him that I failed to notice he spoke with the broad Scots voice of a neighbour, Mr Downie, but if I had thought of it I would have concluded that, living as he did in the far north, Father Christmas probably always spoke with a Scots accent.

Part III

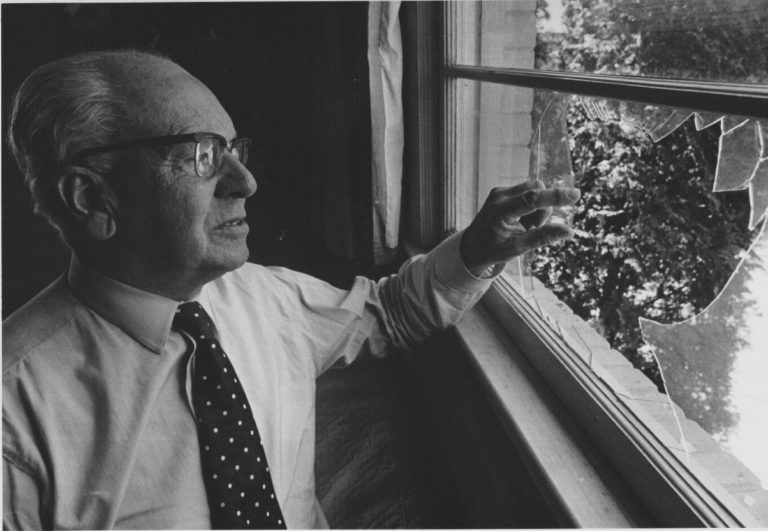

My grandfather, John Vincent, was born in 1870 to Scottish parents, Philip and Hannah (nee Fraser) on their farm which Philip from nostalgia called Fortrose. They were rigidly Presbyterian; John and his sister Emma had to lay out their Sunday clothes the day before and no food could be cooked on that day. According to my mother, Philip bred horses and so was appropriately named. Sadly he died young and the farm was lost. All his life my grandfather grieved over this, stolen he said by rascally lawyers in Dunedin. The battered sign in the garage was a remembrance and he talked of the loss as he lay dying. This accusation rather irked his son-in-law, my father, who was a Christchurch lawyer, but he looked into it and reported that, at a time when unscrupulous lawyers and corrupt banking associates were not unknown in Dunedin, the story was very probably true.

John, his mother and sister, started life again in Dunedin. He presumably had some sort of job there, perhaps starting his engineering apprenticeship, when he met the young Alice Marlowe who had just finished at the Dominican Convent where she had won a gold medal (subject never revealed). Their courtship seems to have lasted a few years – my grandmother was twenty-four when she married – perhaps because of religious differences but more I suspect because my grandfather was doing his time at sea. They duly conformed to what was already an established tradition on the maternal side of my family. According to my grandmother, a forebear in London had taken in a refugee French priest in 1794 who converted the household but since then no Catholic member of the family had ever married a co-religionist. In due course this proved to be true of my mother and me. My ancestry thus has a thin line of Catholicism trickling down the generations through a mass of Protestant scepticism and even a mention of the Pope or a monsignor makes my blood stir uneasily.

John and Alice fell in love, despite or perhaps because of their very different natures; John blunt, upright and socially a little awkward, Alice, feminine, tactful and with an easy charm. Their love was deep and durable, lasting the fifty-five years of their marriage. Perhaps its most difficult challenge came at the beginning, for such a difference in religion was a veto on love in those days. Here my great-grandmother, Hannah, displayed a courage which would have impressed a wartime hero. She thought about it and said to her son, “John, two faiths canna lie on one pillow. Ye’d better turn.”

Turn he did, being received into the Catholic Church after a period of instruction. It is doubtful that he believed any of it; receiving the Last Sacraments as he was dying, he managed to give my mother a wink as the priest bent over him. Whatever his beliefs, the Church mattered to Alice and so it mattered to him. All his life he drove the family to Mass every Sunday, gave generously to church charities and was honoured as a saint at the Mount Magdala convent which gave refuge to fallen girls in the days when these still existed. They and the nuns were maintained by the operations of an extensive laundry. The steam machinery required for this was maintained voluntarily by my grandfather. I was occasionally taken on visits to be introduced as a grandson and to relish the delicacies which the nuns baked. The best of these were called, without embarrassment, ‘melting moments’.

On Alice’s side there had been an easier journey. She was born in London in 1874 and came to New Zealand four years later. Her father’s family were Marlowes and the persistent use of Christopher in given names, including mine, testified to an unwarranted belief that we were collaterally descended from the playwright. Of more significance was the fact that my Marlowe great-grandfather suffered from asthma. His doctor recommended a sea voyage. At home (the story comes from my grandmother) he and his wife opened a map and calculated that New Zealand was the longest voyage. Having made that trip, they concluded that there was no point in coming all the way back again and so, with family and furniture, set out for Dunedin.

It was a three-month voyage. My great-uncle Jim, the eldest in the family, was in his early teens and subsequently lived to be ninety-nine. Of his recollections all I can remember is his dislike of the half-literate school teacher, advertised as an attraction for those with children, who smacked him for not being able to remember the date on which “Queen Charlottey” died. His most stirring memory was on the deck in the Roaring Forties, of two men gripping the wheel to prevent the ship broaching- to and of the enormous swells which towered up over the stern until the ship lifted and they passed beneath. At one point in the Indian Ocean they were overtaken by a faster ship and sent their mail across as likely to get to Dunedin sooner. It was never heard of again. What is vexing is that, successive generations having received a tendency to asthma from Mr Marlowe, no-one has ever revealed whether the voyage helped him.

My grandparents were married in the Catholic church at Akaroa in November 1898. It was Akaroa because John now worked on the steam trawlers and larger vessels which called there and he was often away at sea. Alice enjoyed her first two years of married life in a cottage there, buying her fruit and groceries from elderly daughters of the French immigrants who still spoke a broken English. After completing his engineering apprenticeship my grandfather moved to Christchurch to a house of Fitzgerald Avenue (where my mother was born) and to a position maintaining the steam-powered printing machinery at the Lyttelton Times newspaper. In the early nineteen thirties he bought a ship repair business in Lyttelton and ran it successfully, under the unexpected name of ‘H. Smith and Son’, until he retired. My misty memories of being taken there are of a cavernous building shrouded in dust and the clanging of hammers and the danger of tripping over pieces of dismantled machinery strewn all over the floor.

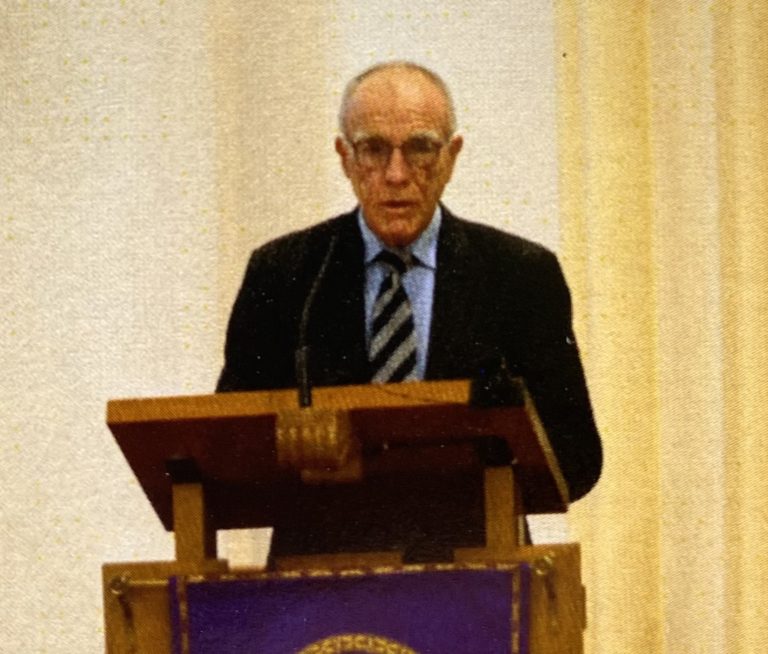

My grandfather died at the beginning of my first year at university. The two ladies and my aunt then moved to a smaller place near Riccarton House and lived out their last years as placidly and comfortably as ever. They lived long enough for my grandmother to sit Sarah Alice (named after her) on her lap. Both died when I was in London and I was never able to express the debt I owed to these dear ladies. I learnt though that family life is lived on credit. As children we live on the generous credit given by the preceding generations and in turn repay the debt by extending it to our own children and (I hope) the level of kindness stays in balance.