Life in Samoa

‘In the palace of the gods what year is this year? ‘ A Song dynasty poet

The house at Papauta was an early European arrival. The original small cottage had been built perhaps in the 1870s, perched on stilts twelve feet above the ground, presumably for coolness since it was high up the hill above Apia and safe from any floods. It was set in a coconut plantation of about twenty acres and like all early plantation houses and their inhabitants its girth had swelled with age. A wide verandah was built around the cottage on three sides and in time this was closed in with walls and tall windows to provide a range of new rooms. Living and sleeping in the house drifted out to these cooler rooms and the old centre was largely deserted. At the back a separate kitchen and bathroom was built, connected to the main house by a gangway – a necessary precaution against fire.

The house belonged for years to an Australian trader, A.G. Smyth, known universally in Apia as Semika. It had been the scene of a tragedy when old Semika and his wife decided to return to Sydney for the last years of their life. For many years they had employed a Samoan nanny, Mary, who helped bring up their children and had become part of the family. So it was accepted that she would go with them to Sydney but for some reason they changed their minds at the last minute and Mary was left behind. She hanged herself from one of the beams under the house.

The house and plantation was bequeathed by Semika to the Samoan Wesleyan Church which was at a bit of a loss to know what to do with it. Neat Samoan fales were built at the edge of the lawn to house two pastors and their families but the house was abandoned to moulder in the sunlight and Semika’s cat withdrew to live wild in the plantation.

It was not the sort of house I would have chosen to begin married life in but there was not any choice. European-style homes were still not common in Apia and those that had been built tended to belong to and be used by the government, the bank, the trading houses and other sources of European secondment. As my wedding approached, Auntie Mary Croudace, Eileen Powles, the High Commissioner’s wife, and I looked with increasing desperation at anything that might be suitable or even possible. Finally, I bumped up the long rutted drive into the plantation at Papauta to gaze with a sinking heart at an old, abandoned house that had not been painted since Queen Victoria’s time, if then. Wisteria which had been trained along the front of the house had collapsed along with the rusted iron frame that had held it and some of the steps up to the front door had rotted away. Inside its large rooms were largely empty of any signs of habitation except for a flourishing population of plantation rats. I took it.

Some sort of clean-up was urgently required. With my wedding approaching even my easy-going father-in-law might pale at the sight of his daughter’s future home. I bought quantities of paint and with the help of the Government House driver and his brother set about brightening its appearance. Painting meant balancing on rather rickety supports twenty feet above the ground while trying to slap away mosquitoes and mop your forehead simultaneously. It was quickly decided that we would paint only those sides of the house visible to visitors as they approached from the drive. The result, gleaming white with blue windowsills, was impressive though anyone who went around the side of the house found half of it still unpainted and it stayed that way throughout our tenancy.

Inside the house was furnished with whatever had been left behind by the Semikas – an old Edwardian double bed in what became our bedroom, a dining-table and chairs and in the fifty-foot long sitting room that ran the length of the front of the house some small armchairs from the 1920s which were prone on occasions to lose a leg to the white ants in a puff of powder. Just before the wedding I went up to the Tokelau Islands in a Sunderland flying-boat and, when they heard of my impending marriage, the hospitable people of Nukunono almost filled the plane with their soft pandanus mats, along with drums and fly whisks less immediately useful to the newly-married. Unrolled, the mats covered the whole of the sitting-room, bedroom and dining-room floors.

Our bedroom was a covered verandah which ran down the side of the house. Raised like the rest of the house on pillars above the ground, it looked into the tops of the plantation’s coconut palms. In the daytime their fronds clattered pleasantly in the trade wind. At night they came into their own when the moonlight silvered the palms which barely moved in the land breeze. The room had tatty linoleum on the floor and chik-chak lizards on its faded walls but we never again had such a beautiful outlook.

The other rooms in the house simply stayed empty and unused, including the empty and echoing room, which we called the ballroom, which led to the kitchen reached by six feet of gangway. This sported a bench, running water and cupboards inhabited by rats but no stove. For months Julie cooked all our meals on a primitive arrangement which consisted of an upended jar of kerosene which fed its fuel through to two asbestos coils which produced a rather unpredictable flame so that heat could be adjusted only by moving the saucepan towards or away from the flame or hastily turning it off altogether if the kitchen seemed likely to catch fire. Then, by one of those mysterious decisions of governments, an electric stove and station-wagon unexpectedly arrived from Wellington and we lived in luxury.

Beyond the kitchen there was a shower and a bathroom containing simply a bath, with no taps or anything else. There was of course no hot water in the house so using the bath involved a procession of pots heated on the kerosene stove. It was a slow business and when I was in the bath only my wife could bring pots to adjust the temperature. I doubt we used it more than twice. Beside it was the most agreeable room in the house, the lavatory, a little room with open trellis walls built out from the side of the house and beside the oldest avocado tree in Samoa. The trellis was embroidered thickly with sweet-smelling honeysuckle and little birds flew in and out, undismayed by your presence. Half way through our time there the lavatory pan fell through the floor and continued to sit in undiminished dignity on the ground twelve feet below but the lavatory kept its charm until the end.

By the time of my marriage I had spent almost a year in Samoa, living in a flat under an enormous mango tree in the garden of the Casino Hotel, woken regularly by the thump of mangoes falling on the roof. The Casino, a graceful wooden building looking across the Beach Road to the sea, had been built by the Germans as a barracks for their officials and it now performed much the same service for New Zealand administrators and visitors. It was run by Mary Croudace, a woman of advancing years, good sense and great charm. There had, rumour said, once been a Mr Croudace but of him nothing was known. The love of Mary’s life had been a US Marine major-general during the war and a photo of him in a silver frame always stood beside her bed.

The term hotel was a misnomer; it was really a boarding-house which came to life after dinner in the evenings when Mary, yipping and hooting in the approved Samoan style, would take the floor to start a round of dancing. She was a party girl and could effortlessly sweep up the floating population of the Casino, which might range from the visiting Bishop of Polynesia through a studious German archaeologist to tourists off the monthly steamer. Whatever raffish elements there may have been in her past, Mary now led the Children of Mary and enrolled me to be organist and choirmaster in the cathedral further along the beach. Her nature was not an unfamiliar one in Pacific seaports then – a carefully maintained respectability floating on a deep knowledge of the world. When a Canadian destroyer visited some enterprising person opened a brothel at the back of the Casino. There was uproar in the middle of the night after someone’s clothes were stolen. Mary must have put an end to the fighting but in the morning none of her regulars would have thought of mentioning it to her.

She was one of the three Schwann sisters who must have enlivened life in Apia as girls between the wars. Of the others, Maggie had become something of a recluse, living high above Apia at Afiamalu where there was nothing but a wireless station. But the third, Aggie Grey, was even more famous than Mary and ran the only other place to stay in Apia. Mr Grey too had faded away but left behind a more substantial memory in the form of a son. Mary and Aggie were reliably said to have been the joint model for Bloody Mary in the musical ‘South Pacific’.

Aggie too was merry but less respectable than her sister. I remember drinking whisky with her in her sitting-room (perhaps in quantity) when she roundly declared, “I like a man who leaves three tracks in the sand when he walks on the beach”. Unlike Mary she usually had an elderly “friend” who lived in the hotel and poured the drinks.

She had as a permanent boarder, Major Brundle, a shabby derelict who was probably one of the last of the ‘remittance men’ who had been a feature of the Beach since before Stevenson’s time. What army had been so easy-going as to give him his rank was never clear but Aggie showed her genteel side in always referring to him as Major Brundle, even after the great falling-out. This occurred at her New Year’s Eve party when, in the middle of a wet season downpour, all the guests had gathered in the dining-room for a ‘heavy supper’ (entertainments on the Beach always advertised a ‘light’ or a ‘heavy’ supper). The rattle of conversation was silenced by the appearance of Major Brundle on the stairs that ran up one side of the room, clad only in a pair of sagging underpants. He shouted “Haven’t any of you buggers got a home to go to” and turned back to his room, his underpants sagging even more perilously.

This was an expulsion offence and the major disappeared. Where he went was unknown even in a small society like the Beach but an oddity of the major was that he seemed to exist only when Aggie’s eye was on him. He re-emerged a couple of months later when a storm had scattered Aggie’s little fleet of tugboats and barges which offloaded cargo from ships in the bay. He telephoned the hotel: “Mrs Grey, I just wanted to speak to you about the damage to your boats”. Aggie was softened, saying ‘That’s very kind of you Major Brundle”, when he continued “What I wanted to say is ‘Ha, Ha, Ha’. That was the end and, once Aggie’s eye had finally been withdrawn , the major was never seen again by anyone in Apia.

My official position was External Affairs Officer working for the High Commissioner who, to reflect Samoa’s approaching self-government and independence, had just withdrawn from his old rooms, the German-built Central Office on the Beach, to Government House up the hill at Vailima, the home built by Robert Louis Stevenson. He and I had desks on the Vailima verandah and no later office rivalled it as I sat in the shade of the scarlet bougainvillea that surged over the portico, smelling the scent of the sweet white ginger and looking several hundred feet down the hill to Apia and the white surf marking the reef.

From my desk I could look into the dining-room still holding the heavy sideboard where Stevenson, mixing a salad, had turned round to ask “Do I look strange” and then collapsed with a stroke. On the other side, over the verandah railings. was an expanse of lawn which might reveal Eileen Powles leading out a group of reluctant recruits from the jail to weed or replant the annuals, or much merrier a gathering of one of the Women’s Committees, a colourless New Zealand name for a lively village institution. They did much good and no doubt gathered at Government House to do even more but what I remember is their dancing on the lawn with the cheerful songs and sly bawdiness that seemed to be the preserve of middle-aged Samoan women. The Samoan language has given my family the indispensable word musu, untranslatable in English but meaning resentful, uncooperative and silent. My subsequent experience from New Zealand to the Marquesas suggests that Samoans may be the most consistently merry branch of Polynesia.

Dick Powles. though initially wary of being saddled with a “spy” from Wellington, saw in me the possibility of an aide-de-camp which he had always wanted. He even showed me a suitable sword which I firmly declined as not having a uniform. Nonetheless I found myself doing many of the tasks of an aide-de-camp. I paid formal calls in the High Commissioner’s name on the captains of visiting naval vessels, usually British, Australian or New Zealand. These involved a hospitable drink or two in the captain’s cabin and sometimes when being piped over the side to my launch bobbing below I had to hold on with special care to preserve my government’s dignity.

Other visitors required some improvisation. The Tongan royal family made occasional visits on the Union Company ships that travelled round the South Pacific to Auckland. Queen Salote had been an earlier problem. She was too large to climb down the rope ladder into the waiting boat. Instead a cargo derrick lifted her on a platform down to the launch, but at night because she was shy.

Perhaps because of this her son, Crown Prince Tungi, came to Samoa by air and I was deputed to greet him at the airport and bring him into Apia. There was an immediate difficulty. Tungi was built like his mother and could not be fitted into the back seat of the High Commissioner’s Oldsmobile, large though it was. While I expressed my warm welcome to the prince, the driver and I sweated to push the front seat as far forward as possible so that Tungi could be accommodated in the back. In the end we had to reverse the struggle and move the front seat to its back limit. So Tungi travelled into town in the front seat beside the driver while I crouched in the narrow space left in the back, with my knees around my ears.

The difficulty than shifted to the formal dinner that night. Stout though the Government house teak chairs were, they could not manage the royal bottom. I tied two together with strong cord and then spread a black cloth over them to make a decorous and sturdy seat for the prince. As dinner progressed and Tungi held forth with his usual (and entertaining) enthusiasm, I looked nervously across the table from time to time but the makeshift seat performed splendidly and, enveloped in the prince’s generous size, did not even hint at its improvised shape.

One of my less formal duties was to keep an eye on the Powles’ two Labradors, Tasi and Lua. After dinners at Government House the guests would sit in a semicircle of chairs in the drawing-room upstairs. On these occasions it was my unspoken duty to stir the dogs along with a furtive foot when they were tempted as they often were to entertain the gathering with lively representations of sexual intercourse. Worse could happen at lunch when ladies in light tropical frocks might suddenly feel a cold nose pressed into their thigh, with a shriek and spilt soup unless I was vigilant.

Other duties were even more demanding. I had to call on a printer to tell him that he was being expelled from the territory for drunkenness and would have to leave on the next steamer. He wept, his wife wept and with any further nudge I would have too. Almost as glum was the burial of a young man killed playing football. These were the last days of the High Commissioner (a New Zealand euphemism for governor) as the leader of Beach society and he thought he should be represented. It was the height of the rainy season and the grave when we got there was an oblong of muddy water. The coffin when committed to the deep reappeared. After a pause a respectful foot pushed it down again. It kept returning even as mourners pushed it down with poles. As I stood mesmerised with the rain trickling down my back, rocks were piled on the coffin and it disappeared for good. Worst of all was the murderer from Niue brought to Samoa to be hanged. Apparently there had to be a government witness and the High Commissioner thought it should be me. Only the man awaiting execution could have been more relieved than me when his reprieve came through.

Otherwise desk work could range from issuing visas to playing billiards with the butler when the flying-boat could not bring the mail and I ran out of work. A staple was the laborious coding or decoding telegrams for Wellington, a chore which greatly increased as the details of ending Samoa’s period of trusteeship were thrashed out. We had no cipher machine and used the old one-time pad, still one of the most secure coding systems devised and rather more secure and complicated than we required. A sheet from the pad, used only once as the name suggested, was used to add numbers to produce a set of five-digit groups which, if your arithmetic was meticulous, could be decoded with an identical sheet in Wellington. Then you took the result down to the wireless station in Apia, an elderly house of coral cement, which you entered by stepping through a window on the verandah (the wall polished by decades of bottoms sliding over it) to hand it to someone hunched over a Morse key. Little seemed to have changed since the Germans built the station and this modest building was one of the reasons New Zealand forces landed in August 1914 – wireless stations were a key in directing or reporting naval movements in the Pacific.

One of the more pleasant tasks, sitting on that verandah with the trade wind stirring your hair, was drafting thoughts about Samoa’s constitutional progress for Wellington to consider. Dick Powles did not enjoy writing and handed this over to me. The most formal requirement was the monthly report to the Minister of Island Territories on which the Minister would nominally offer some comments by the next mail. Dick’s experience had left him unfamiliar with the underground machinery of government business and he believed that the Minister carefully read his reports and replied with his own thoughts. This innocence was rudely threatened when by some departmental mischance our report was returned to us with a cursory summary suggesting there was little for the Minister to read and a return letter for his signature saying how much he had enjoyed the report. I buried the whole bundle in the safe.

All this was optional from the point of view of External Affairs who had sent me. They wanted detailed reporting on Samoan attitudes as they adopted a constitution and took the final steps towards independence. So I spent a considerable amount of time travelling through Upolu and Savaii, explaining the meaning of the impending changes and listening to what people had to say.

Samoan politics had a marked resemblance to those of 18th century England in that power over land and politics was the preserve of a gentry known as matai, usually translated as chiefs. Each chief, usually but by no means always male, was the head of a more or less extended family but, unlike Georgian England, was originally elected by that family. Matai titles were ranked in an ascending order of influence and power. There was a snobbish element in this and, like Jane Austen on old baronetcies, there was no embarrassment in enquiring “Is it a good title?” when hearing of someone for the first time. But there was also political power: old titles might have accumulated a growing base of families and small clans to the point where they were locally and even regionally dominant. At the top were the four “royal” titles, each of which had the allegiance of a significant part of the people. Determining their future was a particularly sensitive task for the drafters of the new constitution for it was the struggles among these grandees which had brought European interference and ultimately annexation in the 19th century.

The higher the title the less likely it was to be chosen by direct descent (though the Malietoa title had a tradition of going from father to son) and powerful titles could lie vacant for months and even years until the various family groups could reach consensus. To complicate matters further, a particular rank could be acquired but the power that went with it might be weakened by the shortcomings of the holder. Even the grandest titles could fade with a succession of inadequate choices. This in my time had overtaken one of the four royal titles.

The local chiefs controlled village affairs, sitting in council at least once a week, so the practices and compromises of democracy were ingrained by long familiarity. Only they could vote or stand in the national elections. The resulting small number of electors produced another parallel with Georgian England: treating or buying votes. New Zealand’s ordinances on corruption had only partial success in dealing with the inevitable consequences in electorates with perhaps only thirty or forty voters. A candidate in one hotly-contested election that I remember was said not to have eaten at his own expense for a month before the vote.

So when I arrived at a village a seasoned if conservative group of local politicians would be awaiting me in the council fale on the village green and open to anyone else who cared to hang about and listen. Proceedings opened with the preparation and serving of kava. A girl chewed the root and strained the result into a bowl; its contents in cups of polished coconut shell were then served to the guest and the others in order of their rank. Speeches of welcome were made in the traditional extravagant style. Some visitors claimed that their arrival had been compared to the Second Coming. I did not rise so high but it was normal for thanks to be given with copious Scriptural references that you had brought light to a gathering hitherto sunk in the deepest darkness. This was not expected to be believed, nor was it crafty flattery – simply the way welcomes had been phrased for centuries.

Then I spoke through my interpreter, Papali’i Poumau (a good title), to explain the coming changes and their timetable. They listened carefully, too good-mannered to wonder at being addressed by a twenty-four year-old in white shirt and shorts. Their questions tended to focus on whether New Zealand would continue to assist them after independence. The Samoan word for independence, tuto’atasi, means standing alone and initially raised some apprehensions about being left friendless and my most important task was to give assurances of continued support. After that it was time for a meal, invariable pisupo, tinned corned beef (from English ‘pea soup’), taro and palusami, steamed taro leaves wrapped round a thick coconut cream. Samoan hospitality was based on the traditional walk from the last village which might take up to a morning. When it had shrunk to fifteen minutes in my battered Landrover the resulting sequence of village meals became something of a trial.

As my wedding approached I was faced with the need to make some arrangements. I had never organised a wedding before and my inexperience showed. I had the vague notion that brides hated getting wet so I suggested a date later in the dry season. It was years before I was allowed to forget this gaffe. A much nearer date was chosen, in February the middle of the wet season, though Eileen Powles claimed bravely but inaccurately that there were many fine days in that month.

Being a man, I turned to arranging the liquor supply. Drink since the old League of Nations Mandate had been sold only from a government Bond subject to a points system, based on the fiction that Europeans in the tropics required some alcohol for their health. Over time the administration of this system had been transferred more realistically from the Medical to the Police Superintendent. Given that it would be the wedding of the year, Alphonse airily waived the rules, suggesting that I help myself. The Bond had years earlier made an unwise purchase of a stock of Pommery champagne which it could not dispose of – drinkers felt that they got better value for their points with beer or whisky. So I bought it all at a giveaway price. Every third bottle had to be thrown away but even so I had a copious supply of good champagne which lasted not only through the wedding but also till Caroline’s christening almost a year later.

I sought a priest to perform the ceremony. In a last outing of the long family tradition, the bishop declined to marry me to an Anglican but asked if he could come to the reception anyway. I would have preferred Father Alan McKay who ran the mission station in the far west of Savaii where I had stayed two or three times. His family were among the Scottish immigrants who had come to Waipu from Nova Scotia. How they had become Catholic was even more of a mystery than it was for me. Alan went back to his home town and had a drink with some of the aged locals who peered suspiciously at his Roman collar. As he talked and his family connections became increasingly apparent, one looked at him in horror and said, “Ye’re no a McKay?”

He was away so I settled for a likeable American, Father Roger Labrecque, who subsequently went to the Vatican and rose to be Monsignor Labrecque. The Church mandated not a conversion but some instruction before a mixed marriage. Julie’s interest in theology was that of a lifelong Anglican and not much instruction seemed to have been imparted in their two sessions. One of her many advantages for a foreign service husband was that as a journalist she was happy to ask questions which a diplomat might have hesitated to raise. She immediately asked Roger whether women were a problem for him. He said it had been a difficulty at first but he felt that he was now over it. That was all she reported of the instruction.

Beyond this all other preparations were taken over by an informal Women’s Committee which came together under Eileen Powles and Mary Croudace to oversee decorating the cathedral and the ballroom at Government House, stocking the kitchen at Papauta with tinned goods (proof against the rats), down to taking over a house down the coast for our honeymoon. I was very grateful to them but they seemed to enjoy the task and my helplessness so much that they were perhaps grateful to me.

Julie arrived at Pago Pago in American Samoa, travelling from Auckland on a Pan-American Stratocruiser, a large, double-decked aircraft which was the last of its kind before the jet age. Pago had declined from a naval base into a fishing port but that evening it rose to the occasion. An enormous tropical moon hung over the peak known as the Rainmaker as Julie and I walked along the harbour’s edge listening in blissful silence to the lapping water. We had been six months apart and when a coconut fell from a palm thirty feet above us, grazing the back of our necks, we scarcely noticed.

Julie stayed at Government House, assiduously attended by the butler, Amanono, who virtually gave up buttling to be on hand to supply her with fluffy bath towels, freshly-ironed clothes or anything else she might need. And even the High Commissioner could not be held back from putting his hands around Julie’s waist in wonderment at its nineteen-inch span.

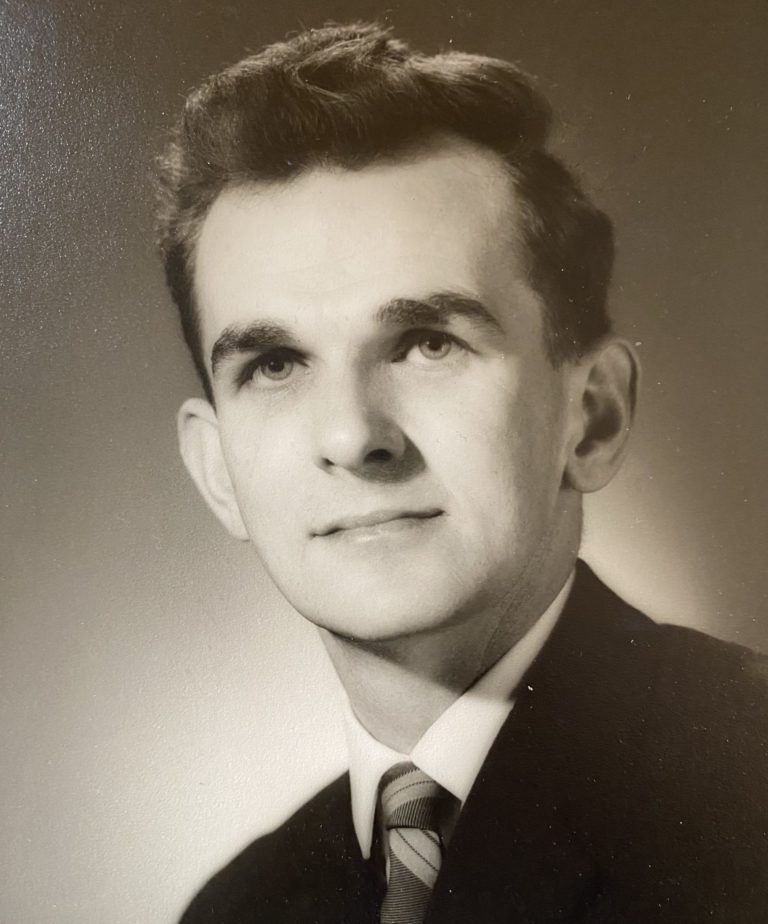

Overseas arrivals for the wedding were select, consisting of my father and mother and Julie’s father and uncle, Colin Austin, soon known to everyone including the house-boys at Vailima as ‘Uncle Colin’. Wedding presents were equally select, consisting largely of gilt silver teaspoons which were available in Christchurch and simple to post, though my parents presented us with a new Ford Anglia.

The wedding day turned out to be one of the wettest of the year, with monsoonal downpours sweeping up the hill from the sea. The ceremony was at four in the afternoon but according to Mrs Powles Julie was in her wedding-dress by nine-thirty. Ancient custom excluded me from Vailima that day but she said excitement passed the day for her, along with being photographed in the hallway, leaning on Stevenson’s writing chair beside the anomalous fireplace. The chair had an enlarged right armrest on which tradition said he had written some of his last works. On either side of her were the two Government House dogs wearing with Labrador stoicism enormous white bows for the day.

At four I was at the altar rails in Mulivai Cathedral, though my wait was just long enough to be fashionable. A quick glance with my Quiz Kids experience told me the church was almost full. The Children of Mary were there, their ranks a little depleted by pregnancy but this was an occupational hazard which Mary Croudace rose above. They could not sing, not so much because the organist was standing at the altar but because it was Lent. The normal coral cement of the walls of the church had disappeared under fine mats and banks of vivid flowers.

A sigh floating up from the congregation told me that Julie had arrived with her father, The earlier part of the ceremony was enlivened by our three-year-old flower girl playing a mouth organ until her mother was able to dart from her pew to retrieve it. Otherwise all I remember is the two witnesses, the great Tupua Tamasese and Ash Levestam the Secretary to the Government, shuffling up to listen as we made our vows, and feeling as I put the ring on Julie’s finger that what had started when she walked in our drawing-room door was now sealed.

Then we drove up the hill to Vailima where Julie, assisted by her friend Fialaui’a and her schoolboy brother Efi Tamasese (now Samoa’s Head of State), changed into a pink ‘going away’ dress. Downstairs the reception was getting under way in the ballroom, a large room with posts and railings but no walls. All the posts had been sheathed in palm fronds dotted with red hibiscus flowers and fine mats had been laid on less busy parts of the floor. On a long table was the wedding breakfast which featured a huge pig roasted whole and given to us by Amanono. The rain roared on the tin roof as ancient chiefs arrived, shaking the water from their umbrellas and congratulating me on the rain which promised a fertile marriage –theirs was the only weather prediction which proved true.

I made some sort of speech, of which all that remains is getting a laugh for saying “Thank you for the corker tent” to the Powles, though the point of the joke has vanished. Then Julie and I opened the dancing, Samoan dancing, though fortunately I was too shy to inject the lewd notes required on these occasions. When the time came to leave the High Commissioner’s car drove us through the darkness to our honeymoon cottage while I lay with my head on Julie’s lap listening to the rain.

The cottage was almost an hour’s drive down the coast. It belonged to the Western Samoan Trust Estates, confiscated from the Germans at the beginning of the first war and since run for the benefit of the Samoan Government, and though much smaller was of the age of the Papauta house. It was lit by kerosene lamps and had a fridge unusual in that it also ran on kerosene. I would have thought this an impossibility and it was, not because of any flaw in its science but because the pilot light had gone out and neither I nor the Solomon Islands girl who looked after us could relight it.

The next morning as Julie and I lay talking comfortably and watching the sun creep over the floor there was a roaring in the courtyard outside. Julie said, “Oh my God, it’s Daddy and Uncle Colin” who were on their way to catch the flying-boat which took off from a wide stretch of the lagoon near the cottage. After that there was no choice but to get up and scrounge for breakfast. The Solomons girl, who had no English and little Samoan, had been unstrung by Colin’s voice, framed to carry across a large paddock in a howling southerly, and had taken refuge elsewhere.

The honeymoon, on an empty beach of white sand curving away in the distance overhung by palms and bordered by a jade-green sea which darkened to deep blue out by the reef, did not hold us. Julie was bitten by a sea snake, luckily non-venomous; the Solomons girl had vanished from the haunts of man; and most of all we were burning to get started in our new home. After three days we were back in Papauta where my mother had covered some of the chairs, there were sheets for the bed and rat poison had been laid so that when you opened a kitchen cupboard there were now dead as well as live rats.

There were the usual adjustments to living together. Every morning for a week Julie cooked me a mutton chop on our awkward stove. When I mentioned as gently as I could that I preferred tea and toast Julie was astonished, “But men always have chops for breakfast” – her father did. These differences were absorbed as Julie went about the house singing “ I’ve got a man of my own.”

Then we had our first falling-out, the result of an unbelievably foolish remark of mine that over some issue she needed to grow up. A frigid silence fell as we prepared to go to bed. The Edwardian bed, even when new, was narrow and built for intimacy. Age, however, had caused its wire base to sag into a deep V so whoever got in ended up at the bottom of the V. This was no problem for the newly-married except when there was a coolness: there was no other bed. So each of us perched uneasily on the outside edges of the bed but as we fell asleep we rolled down to end up together in the V. In disapproving silence we hauled ourselves back up to the edge only to end up in the middle again. When this happened for the third time we burst out laughing and put our arms round each other.

The heat took some getting used to, though Julie never complained. The only air-conditioning known in the territory was in a prosperous planter’s new car, a marvel we all took a ride in to experience the misted windows. The house, despite being high off the ground and ringed with tall windows long since rusted permanently open , was hot. The trade wind which came up the hill bringing with it the distant sound of the sea on the reef, made the palms clatter but barely entered the house. Passing showers of rain pounding on the tin roof could make conversation difficult. But in the tropics the body becomes very sensitive to variations and I woke up shivering one night in the dry season to find that the thermometer had dropped to a chilly 71.

We acquired a ‘house-girl’, a middle-aged woman called Tala who did the washing (there was no machine not even a mangle) and some cleaning but was otherwise prized for her talent at adjusting the short-wave radio to fill the house with cheerful tunes, often from Radio Moscow. With the help of my driver a henhouse was built behind a fragrant gardenia hedge and seven hens installed, despite his earnest insistence that they would not lay unless I had a rooster as well. They did lay but you had to be quick, speeding down at the first cackle and even then two rats might be found rolling the egg away. The Semika’s cat, now known to us as Henry Wendt after our equally shy plumber, made shadowy appearances, cautiously testing the reopened house.

We usually ate dinner in the evening by the light of two candles in old silver candlesticks, not so much because of romance as that the power tended to fail around six in the evening. The day closed as it started, with the melody of hymns sung by the pastors’ families sitting in the lamplight of their fales at the edge of the lawn.

There was another religious note in life at Papauta. Down the hill below us was the village of Tanugamanono, settled as the name suggests by refugees from the island of Manono perhaps fleeing a volcanic eruption in 1913. At occasional times its church bell would commence a slow toll at intervals of a minute. It was a passing bell, hitherto known to me only from Wilfrid Owen’s poem. It would toll for a few hours or perhaps a day and its measured pauses gave solemnity to the waning hours of someone’s life. The halt was dramatic, and followed by quick strokes that gave the age of the deceased. It offered some confirmation of Edmund Burke’s surprising citation of the slow tolling of a bell as an example of the sublime.

Settling into daily life, we went with the Powles and other notabilities to a recital given by the pupils of Avele Primary School near Vailima. The children sang ‘items’ ( a term beloved of New Zealand schoolteachers), one of which was “Little eyes, I love you”. From singers who knew no English this came out as “Little arse, I love you” and as it was repeated with increasing vigour the facial muscles of the visitors came under some pressure. The tension was relieved by Julie suddenly rising from her chair and bolting into the bushes. The matrons on the stage smiled and nodded gravely to one another. It was the first sign that Caroline was coming.

After three months Julie’s pregnancy went calmly and we were wrapped into the social life of the Beach and its expatriates. Kind ladies called with food and advice in the first weeks and we were swamped with dinner invitations. Arranging these and any other gatherings was greatly simplified by the Apia telephone system, an example of social media before there were any others. When you asked for a number the operator, who seemed to know the movements of the whole town, might tell you that the person was out – “I just saw her going into Burns Philp” – or “I think he’s at lunch with his neighbours, shall I try their number?”

Summoned by these kindly calls, we sat at dinner tables bathed in the sentimentality that went with being newly-weds and, by the rare skills of expatriate housewives, ate the overcooked food we would have eaten in New Zealand. The wife of the Chief Judge, a slightly eccentric Frenchwoman, was different. Her cooking would have delighted Talleyrand. At her table I would fill my plate, have a hearty second helping but when I declined a third she would shout, “What! You do not like my food?”

As a result of all these dinners we acquired a large number of social obligations and had to give an equally large number of dinners in return. In putting compatible lists of guests together the bores were inevitably weeded out. Left with a handful no-one else wished to have dinner with I had an inspiration and we invited them as a group to a bores dinner (not acknowledged as such). It was a great success. The bores all bored away happily, and I learnt an unexpected lesson for future entertainment.

The only other recreation was an occasional picnic, in a land and climate designed for picnics. The Powles did so in style. A car would go ahead with the butler and a houseboy while we followed half an hour behind. By the time we arrived at some idyllic beachside place, rugs would have been spread over the sand, folding chairs set up and warm food and cold beer laid out for lunch after the ritual swim.

Our own excursions were less grand. We took the stony track over the Mafa pass (often closed in bad weather) to the less-populated south coast. We would choose a deserted beach and the only time we ever had company was when three fishing canoes drifted by, directed with blasts from a conch shell – a touch of old Samoa which emphasised the timelessness of the scene. As soon as the food was unpacked we dived into the jade-green waters of the lagoon, its calm emphasised by the roar of the waves breaking into brilliant white surf on the reef further out. As Julie got heavier she could slip off her cotton lavalava when she got into the water and lie there comfortably. In the warm water I could spend up to an hour with a snorkel slowly following schools of brilliantly-coloured reef fish. On one occasion I almost bumped into a thin silver streak which turned out to be a sea snake having a nap. Given our earlier difficulty with sea snakes I cautiously back-pedalled with my rubber flippers until out of range.

In the course of these excursions we learnt a lifetime lesson about Labradors. We had just inherited Tasi from the Powles and took him with us for a day on another beach along this beautiful coast. Remote and empty, it was like a movie set for a tropical paradise. As usual we immediately plunged into the water for an hour while the dog watched us, sitting patiently by the rug and picnic things. When we had lunch, however, a square of fruit cake wrapped in cellophane could not be found. Julie and I looked everywhere, helped by the equally concerned dog, until Julie thought to inspect Tasi’s jaws, still decorated with crumbs of fruit cake.

In the middle of the year we had a new High Commissioner. With the inauguration of Cabinet government Dick Powles had completed his eleven years of work for self-government and it was time to lower New Zealand’s profile and make a change. The replacement was Jack Wright, a man of blunt common sense who had been Secretary of Island Territories and had retired to grow coffee at a plantation in the hills of Upolu. He also had the advantage of being a nephew by marriage of both Mary and Aggie. They were pleased and a little disappointed. Aggie liked to reminisce about earlier governors, starting with the imperial splendour of Governor Solfe in 1912 and moving through the succession until she would say, “Now … there’s my nephew Jack”, her voice trailing away.

Although the period of full German control had been short, 1900 to 1914 when a small New Zealand force arrived, there was still a sizeable number of descendants of German settlers whose occasional nostalgia for those days was expressed mainly in criticism of New Zealand’s rule. The genial Minister of Finance, Fred Betham, showed at least how his parents had felt, naming him Gustav Frederick Der Tag Betham. His wife invited me to afternoon tea shortly after my arrival and with her female relatives launched a bitter assault on New Zealand, unpleasant for a twenty-four year-old out of his country for the first time.

Other reminders were less fraught but could be equally surprising. I sat next to the Medical Superintendent, Hans Thieme, at a lunch. He had been taken prisoner during the war and when I asked him where he said, Stalingrad. I thought about this for a moment and when I looked up he was watching me with the sad smile of someone who has seen too much to tell.

I enjoyed an intermittent friendship with an old German settler, Alfred Jahnke – intermittent because we did not meet often and, even after forty years of the New Zealand presence, his English was still uncertain and heavily accented. Before emigrating in 1912 he had been assistant curator of the Berlin Botanical Gardens and had the privilege of escorting the Kaiser around the gardens. I was fascinated to met someone who had known the Kaiser but all he could report was that His Imperial Majesty was not much interested in botany.

He acquired a coconut plantation down the coast from Apia. He told me that in September 1914 he was awakened after midnight by a thunderous knocking on his door. He opened it to find two German naval officers and eight ratings crowded on to his front veranda. They had rowed in from the battlecruiser Scharnhorst which with its sister Gneisenauwere lying out of sight some distance off shore. They asked Alfred if it was true that New Zealanders had seized Apia and when he confirmed this said that they would bombard the town next day. Alfred advised against this (he told me), arguing that if they won the war it would be better to recover Apia intact and if they lost there was no point in shelling the town anyway. They may have taken Alfred’s advice because the next day the two battlecruisers appeared off Apia, causing considerable alarm, but moved away without opening fire.

When the Powles left we inherited their Labrador. Tasi adapted comfortably to his loss of standing as First Dog and enjoyed making visitors welcome to the house. Every day he was fed a bowl of rice, mutton flap and paw-paw at the bottom of the kitchen steps, watched longingly by Henry Wendt who would dart in to take a quick sip. Retreating every time the dog growled he extended his raids until his presence was accepted and before long the dog and the wild cat could be seen lapping peaceably together every day. Tasi was the same when Caroline arrived, staring resentfully at the intruder as Julie carried her about, until time again made peace. One evening as Julie fed her he stretched forward to lick Caroline’s foot gently and after that he slept beside her crib.

Caroline herself was due on St Lucy’s day, 13 December, hence her middle name. She was however as cautious as Henry about showing herself. On Christmas Eve we went to midnight mass at Moamoa, the old mission station up in the hills where the superb singing, with that high Polynesian lilt, could only make a retired choirmaster weep. Perhaps it stirred Caroline too because Julie went into labour on Boxing Day.

It was not a good time. The doctor had gone to the Tokelaus and at least half of the nurses were still recovering from Christmas parties. The hospital seemed almost deserted and to make matters worse the baby was the wrong way round. I sat beside Julie holding her hand and mopping her brow, consumed with guilt as the biological cause of this suffering. In the absence of anyone else I managed her needs, calling for bowls and towels with a burst of scurrilous Samoan at a slow-witted nursing aid who was as surprised as I was at words of which I had been unaware. Through the night, as the baby laboriously turned itself around, I was increasingly haunted by the fear that Julie and I would have to deliver the baby ourselves. It did not help that all I knew from the movies was that I would need lots of hot water and some string.

Things improved the next day. The doctor returned and after twenty-six hours of labour Caroline was born at ten to three in the afternoon. A nurse held a purple and yellow baby battered by her long delivery, but when she opened them she had the enormous eyes of her mother. I was awed, not just by pride but also by the feeling that I had suddenly risen a generation, with another now close behind me.

As Secretary of the Council of State it was my courteous obligation to inform the High Commissioner, the two Samoan leaders and other notabilities of her arrival. Malietoa asked me if she had a Samoan name. I said we had thought of ‘Teuila’, the wild white ginger. He waved this away, saying he meant a real Samoan name: “I have decided she will be called To’oa” (To’oa). I thanked him, privately thinking Teuila a more musical name, and thought no more of it until I mentioned it to the Chief Judge. He dismissed it, saying that I must have heard it incorrectly. To’oa was the title of the senior woman in the Malietoa family and was currently held by Salamasina, the dignified headmistress of Papauta Girls School and Tanu Malietoa’s elder sister.

I went back to Tanu who immediately guessed who I had been talking to. He said he had discussed it with members of his family and talked to Salamasina who had agreed to split the title. So Caroline became the joint To’oa and her birth certificate came back with her name recorded by the Samoan official as To’oa Caroline.

Then the ghost trouble started. We acquired Leva (Leva) as a ‘baby girl’ who moved into the room that Mary, the Semika’s nanny, had once occupied. One morning she was very upset. A woman had come into her room in the night and had leant over the end of the bed staring at her. We had had a dinner the previous evening for Reg Barnewall and his wife. Reg, who was an Australian bush pilot now running the fledgling Polynesian Airlines, was also in the improbable ways of the Pacific an English baronet, though probably not the sort approved by Jane Austen. I suggested that the woman was Reg’s wife, going astray on the long journey down the house to the lavatory. Leva rejected this: the woman was Samoan.

In further questions Leva said she wore a puletasi, the dress with a long skirt underneath which the missionaries had introduced, but unusually it was white and she had short hair, not the long plait which was universal in women. It sounded to me like the conventional picture of a ghost polished by years of tales in fales around the lamp and I suspected our neighbours of having passed on the story of Mary’s tragic end.

The story could not be ignored. Assured it was haunted when I first looked at the house, I did not think it useful to tell Julie. As soon as she arrived others lost no time in telling her but equally she thought it best not to mention it to me. Ten months went by in this happy reticence and never was a house less haunted. Now Leva’s fears risked our losing both her and Tala and given our rather remote situation we might be unable to attract replacements. So the first step was to get more details of Mary and her appearance.

Julie rang Gwen McKinnon, Semika’s granddaughter: “Mary’s come back, has she? I’m not surprised, she was crazy about babies”. Julie turned the conversation to neutral enquiries about Mary’s appearance. Mary, it appeared, always wore a white puletasi. Her hair? The usual long plait until Gwen corrected herself: Mary had cut it short in the expectation that she would be going to Sydney.

None of this helped much. For two nights slightly odd things happened in the house, like the dog whimpering in the night, and Leva became more troubled. My explanation was that someone must have come into the house at night and disturbed her – not an unfamiliar happening in open fales and the Samoan language even has words for it. The next evening I locked both front and back doors for the first time and showed her that I would sleep with the keys in my hand. Given that the windows all had steel mesh firmly nailed over them it would be obvious if anyone tried to break in. After my demonstration, Leva finished ironing her best red dress and hung it in the cupboard in her old bedroom, though she would no longer sleep there.

With the keys in my hand under the pillow I slept soundly, awakened briefly by a shower of rain sweeping up the hill at four in the morning, and bounced out of bed at sunrise with a cheery greeting for Leva. Wordlessly she pointed to her old bedroom window. Outside spread over the top of a hibiscus bush fourteen or so feet high was her red dress. The house was still locked and no windows had been disturbed. I hurried outside. The hibiscus was a willowy clump of stems too thin to be climbed. Placing the dress would have required a large step-ladder but in the wet muddy ground there were no marks of a ladder or indeed of any footprints. The dress, when retrieved, was wet and so had been placed there before the rain.

Now we had serious trouble and I sought the help of Roger Labrecque who had much better Samoan. He talked to Leva at length, said she was very worried and offered to come back and exorcise the house if there was any more trouble. But there wasn’t. After that the house went back to being as unhaunted as ever, the dog stayed silent and Leva became her cheerful self again, though refusing to sleep anywhere but in Caroline’s room.

We were left with a lifetime puzzle, the gnawing Mystery of the Red Dress. Years later Julie and I were having dinner with Lee Kuan Yew and his wife in Wellington and after dinner we fell to telling ghost stories, including this one. At the end Julie made some throwaway comment about still not believing in ghosts. Lee leant forward, fixed her with a grave look and said, “Juliet, do not discount the supernatural”. I do, but would do so more comfortably if I knew what happened in the Papauta house that night.

Meanwhile Samoa was approaching the end of its trusteeship or period of colonial rule. The United Nations had decided that the last step should be a plebiscite on the draft constitution and insisted that all adults should vote. This leap to universal suffrage upset many in the matai political establishment but was accepted by them as the ‘gateway to freedom’ after which they assumed the gate could be nailed shut, though a few like Malietoa knew better.

A Plebiscite Commissioner arrived from Wellington and other officials from the UN in New York. We plunged into the mass of detail required in preparing a universal electoral roll, organising publicity, finding returning officers and polling places in often remote villages. Then we were interrupted by a hurricane.

It was the season and Samoa was in the hurricane belt. Its most famous example was the hurricane of 1889 which occurred in the midst of an intermittent civil war and the meddling of the great powers. Tension had arisen among them to the point where three German warships were in Apia Bay, together with three American vessels and a solitary British gunboat. Every commander was aware of the danger of being trapped in the open Apia Bay but no-one wished to be the first to leave. In the end they left it too late and only HMS Calliope was able to inch out with the help, I was always told as a child, of Westport coal. As she crawled past the USS Trenton making one knot against the wind the American crew, most of whom were to drown, gave her a gallant cheer. All the ships trapped in the bay either sank or were wrecked with considerable loss of life and the rusting wreckage of the German gunboat Adler still rested on the inner reef in our time.

In recent years, though, hurricanes had become rarer and no-one could take it quite seriously when we received the first warning from Nadi in Fiji. When the warning went firm we moved the desks on the Vailima verandah indoors and I went down to the beach to ensure that the emergency services were prepared. Then I went to Papauta to look at my own home but there was not much that could be done with an ancient house on stilts with all its windows open, though it had survived the 1889 storm. Even so the house seemed a better bet than the flimsy fales in the garden. As the wind began to rise I went down to invite the families to take refuge in the house, though with the increasing noise and my bad Samoan it was not clear if anyone had understood.

There was nothing left to do but sit waiting for the storm. The Apia radio station, 2AP, matched the apprehensive mood by playing funereal music until Julie telephoned to suggest something more cheerful. They responded with a burst of jollier tunes but then the power failed and we were all on our own. The night was blacker than anything I have ever known, lit by glares of shivering lightning followed immediately by rolling cannonades of thunder. The noise of the wind and driving rain made it impossible to talk except by cupping your hands and shouting into your partner’s ear. The intermittent flashes of lightning showed a dramatic scene, the coconut palms bending horizontal in the wind.

Julie and I sat in the flickering light of two aptly-named hurricane lamps at one end of the fifty-foot living room which had been the wide front verandah of the original cottage. Caroline bundled up in her carry-cot lay beside us in case the house began to disintegrate. Short of a collapse any thought of leaving the house would have been suicidal. There were crashes and bangs as flying debris hit the house and, riding above the din of the wind and rain, was a periodic sharp crack as a tree toppled over. I was concerned that one might fall on the house which swayed and creaked but did seem to be holding up, perhaps because it had some shelter from the plantation. The wooden shades over the windows, disliked for keeping the breeze out of the house, now helped to keep out the wind and rain.

In the kitchen a door broke loose and began to slam noisily. Walking down the ballroom to see to it I stepped on something soft. Holding up the hurricane lamp I saw eight pairs of wide brown eyes looking at me. The pastors in the fales had wrapped up their smallest children and placed them in two neat lines on the ball room floor. With the door wired shut I returned and sat with Julie though any normal conversation was still impossible.

Around one in the morning there was something of a lull and, though the storm resumed, its fury gradually diminished. Towards dawn we both fell asleep in our chairs and when daylight came the wind was dropping. A quick walk around the plantation in the rain showed that we had escaped fairly lightly. The centre of the hurricane had missed Apia, coming ashore further down the coast. The house and the fales were undamaged, though the drive was blocked by two or three fallen trees. The henhouse had disappeared along with its residents. The coconuts looked strangely dishevelled with the green stripped from their palms but their ability to bend, which was such a striking sight when the lightning flashed, had saved any from being uprooted. Further up the hill, Vailima had also survived, but with the loss of half the teak avenue that led to the house.

Work on the plebiscite started again and in the middle of one morning our seconded typist asked me to take over her decoding duties temporarily. She handed me a message from Wellington which said, “We have it in mind that Hensley’s next post should be…” and there Val had dropped out. I wrestled with the one-time pad, for the last time as it turned out, in my excitement subtracting when I should have added or carrying over the remainders when I shouldn’t until at last the words “New York” appeared. I hurried home in some excitement to tell Julie of the coming leap from fales to Fifth Avenue.

Our baggage was packed under the house in crates made of handsome Samoan hardwood that may have been more valuable than the contents. Hens laid in the straw used as packing and in Manhattan we found two eggs. The cat was relocated to Vailima but it was the end for Tasi the Labrador who we had promised the Powles to put down when we left. The dog was buried in a grave beside the avocado tree, wrapped in a fine mat given by the pastors who did not actually pray but stood respectfully around the grave and helped fill it in. It was the end too of our extended honeymoon in Samoa.