London Calling

Marlborough House, a former royal palace on the Mall, was my rather grand working home for four years from September 1965. It was built by the first Duke of Marlborough at a time when he riding high, both politically and militarily, in the first decade of the 18th century. The building was supervised by his energetic wife, Sarah, who had no hesitation in firing Christopher Wren as the first architect. In a suitable tribute a lush portrait of her by Kneller still hung in one of the downstairs reception rooms. The cost, met by the Duke, was considerable, though he economised by using the government transports that supplied his army in the Netherlands to carry back the attractive Flemish bricks of which the house is built.

The house inevitably became a celebration of his victories. The main staircase featured a continuous and brightly-coloured mural of these. Queen Adelaide, who lived in the house as a royal widow in the mid-nineteenth century, had them whitewashed. There was tutting over this act of vandalism and the murals were restored, brighter than ever. As I walked up and down these stairs every day, uncomfortably close to shattered bodies and a dying horse in its last agony, it was impossible not to have some sympathy with the Queen.

I had moved into these splendours unexpectedly and in some haste. I had been working for two years on a novel status for the Cook Islands, that of “free association” with New Zealand. We were feeling our way – no-one else had done it before – and there were occasional missteps. Least expected, though, was to be summoned by Mac to be told sternly, ”You have infringed the Royal Prerogative”. No such disloyalty had crossed my mind but Mac showed me a letter from the Governor-General, Sir Bernard Fergusson, complaining that in altering the standing of the Queen’s Representative in Rarotonga we had overlooked the courtesy of consulting the Palace. I protested that such archaic concerns should not interfere with the new constitution we were designing for the Cooks and drew a memorable Mac rebuke. Whatever we may think of the institution, he said, we have it and while we do our obligation is to make it work properly.

I was sent to apologise to the Governor-General in person. When I called on him at Government House in Auckland his first words were “You’ll have a drink”. It was two-thirty in the afternoon but this seemed to be more of a statement than a suggestion, and in any case I was there to make myself agreeable. I had no sooner agreed than the butler came in with two tumblers on a tray, each half-full with brandy. I sipped cautiously while Sir Bernard told some good stories about his earlier career and when I was able to leave over an hour later any difficulty over the Royal Prerogative had disappeared into the late afternoon.

I returned to my desk and worked away dutifully for some time when I received another summons from Mac who had just returned from a senior Commonwealth officials meeting in London. As I walked into his room I wondered what new solecism I might have committed but this time what he had to say changed my life.

The London meeting he had just attended had made the radical step of establishing a Commonwealth Secretariat, putting the Commonwealth into common ownership after years of management by Whitehall. It had also agreed on a Canadian diplomat, Arnold Smith, to be the first Secretary-General. The choice was made in a very British way, after weeks of discreet consultations among Commonwealth members. As these consultations proceeded it became clear that Mac was the front runner, with Arnold behind him in second place. Then out of the blue the British suddenly put forward a candidate of their own, a quite unknown governor of the British Honduras.

In the circumstances this could only be seen as a veto on Mac’s candidacy. Why is still a mystery. He looked from the British point of view the perfect candidate but perhaps they mistrusted his homosexuality, known to no-one else at the time but known to the British because of an indiscretion in Singapore in 1949. Or perhaps they had doubts about his security soundness after differences twelve years earlier with MI5 over a Communist staff member. Mac, ever realistic, read the signs. He called on Arnold Smith to talk of his increasing deafness and say that he was asking his support to shift to the Canadian. This put Arnold over the top and gave the infant Secretariat a bolder and more creative head than the British (or anyone else) had expected.

In response Arnold asked if he could find a young New Zealander to be his Executive Assistant and on his return Mac offered the position to me. Despite my excitement I remembered to say that I would have to consult Julie but neither of us was fooled by this figleaf. The need was urgent. Arnold had already moved into Marlborough House which the Queen had kindly made available as the Secretariat’s headquarters and two weeks later we were in London at the St Ermin’s hotel, with three children ranging in age from four years to the baby Sarah at four months.

Rather surprisingly our first task was to organise a wedding. While I lay in bed befogged with jet lag, Julie came in to say that her sister Hebe was pregnant and wanted to get married. I groaned with tiredness from the depths of the bed but apart from groaning almost all the arrangements for the wedding were done briskly by Julie in a city she had never visited before. St Mary’s Cadogan Street was booked with the help of its kindly rector, Father Laughton Matthew, Caroline was outfitted in a red velvet cloak she cherished for years, Gerald locked himself in the church lavatory and could not be freed for some time and for the first and last time we gave a reception at the Dorchester.

After that we could turn to looking for our own accommodation. This is always a depressing start to any posting. The Secretariat’s housing allowance ran to central London where the houses for rent seemed to follow a pattern of impressive drawing-rooms and rather squalid kitchens and bathrooms. In the end we came back to the first house we had looked at, a little Regency house at 14 Trevor Street, just down from the Knightsbridge Barracks whose officers were said to have installed their mistresses in these houses. Caroline and Gerald slept in an airy room on the third or top floor, Sarah in the dressing-room outside our bedroom on the second, the drawing-room was on the ground floor looking out on to the street and the dining room and kitchen were in the basement with a small townhouse garden behind.

The furniture was in keeping with the house, teaching us the first lesson of a British establishment, the need to sit down with care. The bath was heated by an ancient contrivance called a geyser, though a mild flow would have been a more accurate term, and we learnt why housing advertisements made a point of promising ‘constant hot water’. When we put a small climbing frame and barbecue in the garden we received a letter from a neighbour complaining both of ‘some jungle arrangement’ and the smell of barbecuing. But these were all the last traces of a pre-war England. The house was warm, close to the Park and the children’s school.

The two elder children were enrolled at the Hampshire School which operated from a church hall behind Harrods. It had been founded by old Mrs Hampshire but an important feature was her daughter, the actress Susan Hampshire, who helped out at the school and kept fathers happy to deliver their children every morning. It was a cosy sort of school. In later years Sarah, newly-enrolled, would be picked up in the mornings by the Hampshire housekeeper in her Mini.

The children once again had to face the bustle and uncertainty of being moved but the adjustment to London life did not seem too difficult. They liked the school which was full of new things to do including of course drama. Gerald had his first appearance in a school production of The Sleeping Beauty. Contemplating the heroine who was asleep waiting for a prince he announced firmly, “She’s waited long enough” which caused some titters among the lower-minded members of the audience. Outside school there were regular outings to be looked forward to, plays, visits to galleries, the Christmas pantomimes and Caroline’s birthday visits to Covent Garden for the ballet which she loved.

At home there were the still unsurpassed delights of the BBC’s children’s television. I came home once to find Caroline and Gerald crouched behind a chair at the far end of the room, peeping round the edge at ‘Dr Who’ on the screen. “It’s a bit fierce” they explained. This proved to be true of the play, ‘Toad of Toad Hall’, which held them spellbound but the assault of the wild weasels, with bangs and flashing lights echoing round the theatre, required considerable reassurance.

They also liked the nanny, Alison, whom Julie had quickly recruited. She wore a uniform, had been an under-nanny in a grander establishment and found life in a New Zealand house excitingly different. She brought a traditional aspect to the children’s life with a daily walk through Hyde Park to the Peter Pan statue, where Caroline liked being allowed by nanny to push Sarah’s stroller, and where along with the pleasures of the merry-go-round and buying ice creams Gerald even managed to fall into the Serpentine and lose a tooth.

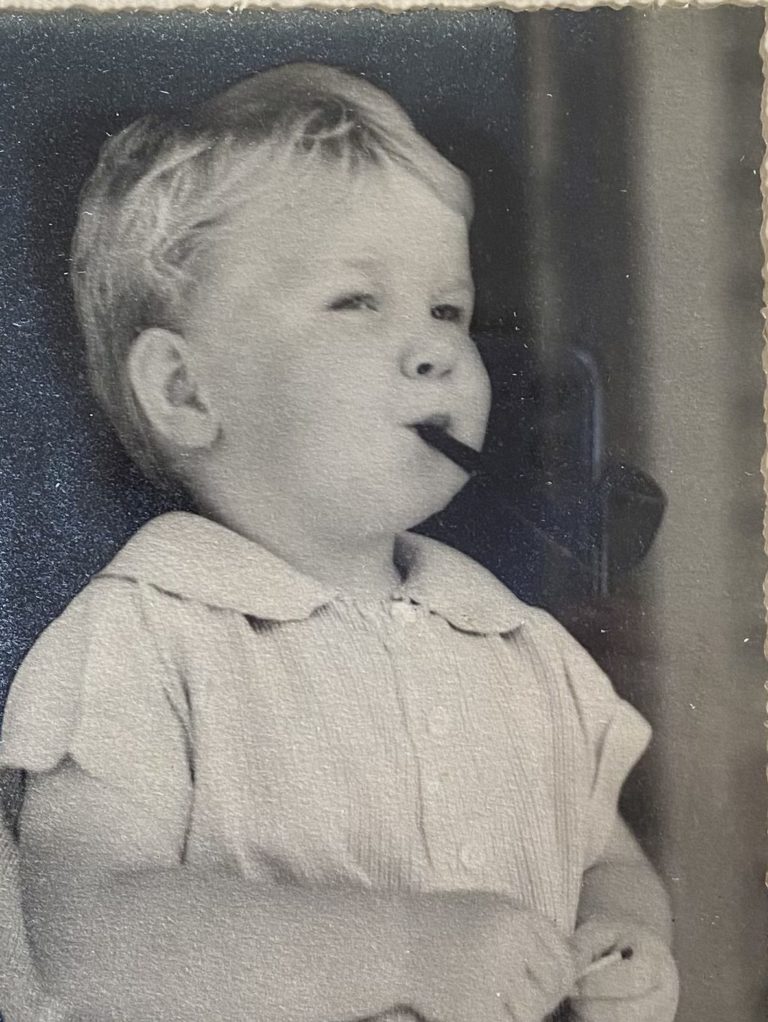

Visits to Marlborough House could induce an air of solemnity. In a photograph taken under the watchful gaze of the Duchess of Marlborough they stare stonily at the camera like a recently-discovered Amazon tribe, though that may have been because Caroline had just visited the dentist. Things could be livened up by a tour of the grounds, going to see the dogs’ cemetery which Queen Alexandra had established in a small grove of trees in the grounds. For great occasions like the State Opening of Parliament they perched on the garden wall, looking over the scarlet soldiers who lined the Mall to watch the Queen’s coach go by. A band was stationed every hundred yards. Each band struck up the national anthem as the Queen passed so that there was a rolling chorus of God Save the Queen sounding in sequence as she travelled down the Mall.

Inside the house they climbed the stairs to their father’s office. There was a lift but it was built to carry only Queen Mary and a lady in waiting, if that. My office had been the royal nursery in King Edward’s day, with little bars across the lower parts of the windows to keep the future George V and others from falling out. Along the corridor was the King’s “library”, the walls covered with imitation shelves and the spines of imitation books with jokey titles. He was clearly not a reader but the children enjoyed walking through the part of the fake bookcases which covered a secret door, allowing the King to enter the room unnoticed, through a screen of feeble puns.

Within the garden walls was an older building, the Queen’s Chapel built for Charles I’s Catholic bride, Henrietta Maria, by Inigo Jones. Its religious orientation had varied with the times. James II was the last to go to Mass there, doing so on Sundays preceded by the Duke of Norfolk carrying the Sword of State. The Norfolks by some mischance managed always to be on the unfashionable side of religious change in that restless century. So the Anglican Duke stepped aside at the chapel doorway. The King said, “Your Grace’s father would have gone further.” To which the Duke bowed and said, “Your Majesty’s father would not have gone so far”.

The chapel had now become a Royal Peculiar, an odd term meaning, I think, that it was under the direct authority of the Queen. But it might have applied just as accurately to the incumbent in our time. He was a rotund, rather jolly cleric whose services, to which Julie and I occasionally went, always seemed to be taken by someone else. He liked to explain the privileges of his position, especially the bright colour of his extensive shirt-front, which signalled that he was above parish clergy but less than a bishop, a sort of Anglican monsignor. When we met him at Ascot even his silk umbrella was in his distinctive red.

Most mornings I walked to the Secretariat, along Knightsbridge and through Green Park and the courtyards of St James’s palace to Marlborough House at the beginning of Pall Mall. It was never a boring walk, partly perhaps because it coincided with the arrival of the miniskirt and some of my fellow walkers were worthy of study. The march of the seasons in Green Park unrolled with the arrival of yellow daffodils, followed by the first appearance of white midriffs hopefully exposed to the spring sunshine, then the summer explosion of deckchairs and those occupying them, some with knotted handkerchiefs over their heads which I thought had been a fiction of the cartoonists, then the drifts of golden leaves and back to gaunt trees again. Walking through St James’s Palace (as was then possible) was less seasonal but had, if only once, an unexpected pleasure. I was walking home on a dim winter’s evening when the sentry I was approaching straightened up and presented arms, and then the rest of my journey through the courtyard was punctuated by the clash and stamp of arms being presented, presumably because the first sentry had mistaken me for one of the minor royal occupants.

While we were still adjusting to the new house ‘Southern Rhodesia’ declared its independence and began a long-running crisis for the Commonwealth which dominated the whole of my time in the Secretariat. Forewarned, Arnold and I left soon after my arrival for the five African countries most affected and spent three weeks there as he laboured tirelessly and successfully to keep the Commonwealth from splitting. This left Julie to manage the endless details and difficulties of settling in. She found the school and the nanny, discreetly made the house more comfortable and helped the children to settle in. I tried to make up for this desertion by returning with a rather fetching leopard-skin pillbox hat for her (now mercifully disappeared) and a crocodile handbag, still in use by Sarah. For the children there were two Ugandan drums covered in zebra skin which after the taste for drumming faded did duty for years as stools in the playroom.

Because I had to travel so much, this turned out to be the pattern of our life in London. In the process Julie had to master some unexpected aspects of life there. After New York there were cultural adjustments to be made. She learnt that if the washing machine broke down there was no point in phoning the repairman, you had to write a letter. She discovered that a bread we both liked in Harrods had been discontinued “because too many people were asking for it”. The bank had to be persuaded to overcome its suspicion of wives wanting to withdraw money. And when I was in Nairobi she managed to conceal from me that she was in hospital with a kidney infection.

She had to abandon her career in journalism but found she enjoyed the sort of social life that only London could offer. The Secretariat was new and interesting and was quickly included in the round of receptions and dinners by which the establishment kept in touch. Explaining to Lord Carrington at a party that she was new to London, he enquired of Julie, “And are you amused?” Malcolm Macdonald, son of Ramsay, bet her that he had been in New Zealand before her, as indeed he had. A charming but libidinous man, his official life had been the reverse of the usual, a sequence of downward promotions. He began as Secretary of State for the Dominions in 1925, moved to a more minor ministerial post, after the war became Commissioner for Southeast Asia and when I met him was High Commissioner in Nairobi. Julie was invited by Pierre Trudeau to go to a nightclub with him (when I was, perhaps fortunately, at home). Her only failure was Edward Heath. When a Commonwealth meeting overran time for the final reception in Marlborough House, Arnold asked Julie to greet the arriving guests. She found Heath, then Leader of the Opposition, standing on his own in the long drawing-room. He was furious. Julie spent ten minutes trying to charm him with complete lack of success, and was relieved to turn away to welcome less irritable guests.

At the top of London social life was the Queen whose concern for the Commonwealth meant an interest in its new Secretariat. At Christmas in a splendidly medieval gesture she sent Arnold a haunch of venison and our modest share kept us eating venison for several days. She also invited him to a number of Palace receptions and Julie and I accompanied the Smiths to the grand diplomatic reception held every year in Buckingham Palace. The ambassadors and their staffs were ranged in a semi-circle around the Throne Room and because he was new the Secretary-General came almost at the end. The Queen emerged from dinner with several members of the Royal Family and talked her way around the room. She was introduced to each of us, chatted warmly with Arnold for a few minutes while the Duke of Edinburgh talked mainly to Julie who was wearing a strikingly slim silk evening dress rented for the occasion, and then moved on.

When the royal party withdrew there was a concerted rush to the bar for champagne. When we did it was to be confronted by a solid phalanx of scarlet backs. The Gentlemen at Arms, old soldiers and veterans of these occasions, were lined up ordering their drinks well before the less experienced guests had thought of it. Then a string band housed in a minstrel’s gallery above the room struck up and we all turned to waltzing. As Julie and I rotated slowly round we both thought that it might have been a source of pride to Miss E. Comyns Thomas, our dancing teacher, to find that even so unpromising a pupil as I could waltz in the Throne Room.

The flow of visitors through Marlborough House was endlessly interesting. They included the distinctly dubious, a Rhodesian spy, those with visionary and totally impractical plans for the Commonwealth and a mercenary soldier, Major “Mad Mike” Hoare. He made several calls to urge us to get his mates together to arrange a brisk solution to the Rhodesian problem. He left his wife downstairs in the hall and the joke that came to mind (“Good morning, Major Hoare, and how’s Mrs W?”) was quenched by the sight of her, huddled in a fur coat and seemingly terrified of him. At the other end were the resplendent – the Emir of Kano in the latest thirteenth century fashions – and others in their national dress. The Nigerian Foreign Minister, whom both of us knew, came in dazzling white and was greeted by Julie with a kiss and the welcome, “Emeka, you look like a baby’s bassinet”.

Most visitors, though, were the day-to-day calls which greased the wheels of Commonwealth cooperation and our knowledge of the pitfalls in making it work. British and Commonwealth politicians and those who hoped to succeed them made a point of coming to Marlborough House to sit in the corner of Arnold’s office, which had been Queen Mary’s bedroom, drink a cup of coffee and set out their message. As a result we learnt a considerable amount and drank an even greater amount of coffee. Sometimes I downed five or more cups in the course of the day’s visits and was left with my nerves twanging like a guitar.

Some, like Jeremy Thorpe, then leader of the tiny Liberal Party, were a little smooth; others like Lady Violet Bonham Carter, the den mother of the Liberals, had effortless presence. Lady Vi and Arnold were to record a TV interview in the basement. Arnold was held up and asked me to stand in until he could come down. If Lady Vi was surprised to be received by a twenty-nine year old New Zealander rather than the Secretary-General she gave no sign and with perfect ease launched into a conversation which held me enthralled for half an hour. I have since treasured a story she told of Mr Gladstone.

As a twelve or thirteen year old she was playing, still in her morning pinafore, in the drawing-room which looked out on to the street when she was horrified to see the beaky face and high winged-collar of the Prime Minister passing the window and even worse coming up to the front door and ringing the bell. When he was shown into the drawing-room she explained nervously that her parents were out but would be home shortly. There was a tense moment while she waited for the great man’s verdict and then he said, “I shall stay”. She managed to remember to ask him if he would like something to drink. He made no reply, walking down the length of the room to the window and then swinging sharply round to walk back for some minutes. This silence shredded the remains of Violet Asquith’s composure and when he suddenly turned to say, “I should like a glass of Madeira”, she collapsed in a heap.

The diplomatic life was extended by my membership of the Travellers’ Club, just along Pall Mall from Marlborough House. Any New Zealander could easily meet the pre-requisite for membership – to have travelled 500 miles in a straight line from London – but the waiting list was jumped when I was put up by the head of the Commonwealth Office. It was then a staid not to say stuffy institution but agreeable once you mastered its arcane customs.

One of them was that the dining room – referred to only as the Coffee Room – had been two rooms overlooking Pall Mall which were knocked into one at some time in the mid-nineteenth century. Nonetheless, women guests having dinner there were required to sit only in the half that had been one of the old rooms and Julie and I had to move if we sat down at a table on the wrong side of the (non-existent) borderline. On another occasion we had some friends to lunch and I came down the stairs after signing my bill to see Julie being ejected from the Smoking Room which, despite its name, was where coffee was served after lunch and which for some reason did not admit women. We gave a wedding reception at the club for Julie’s cousin Penny. The club rose to the occasion, even lighting the tall flambeaux along the street front. The next morning I was stopped by the porter. “One of the ladies left this, ah, garment”, he said, holding up some trousers left when the bridesmaids had changed.

All this looked as if the club was waging a covert guerrilla war against women but it was comfortable, had handsome rooms and Julie liked it. Long after I had ceased to be a member we stayed there when in London. It then featured a permanent resident in Monsignor Gilbey (of the gin family) who had been Catholic chaplain at Oxford for years. He had a bedroom and sitting-room upstairs and the club had even converted its boot room into a small oratory for him. When we came down in the morning there was often only the three of us and were the only times in my life when I said grace at breakfast.

I almost lived there myself in the weeks when Julie and the children had gone to New Zealand on mid-term leave. A solitary dinner in the club meant sitting at one of a row of small tables, each with a lit candle and a book-rest. This was pleasantly tranquil once I learnt to bring a book. Even more pleasant was the discovery that the club had not as time passed adjusted the prices on its wine list and so for the first (and last) time I drank a bottle of Ch. Figeac 1929 at the cost of ten shillings.

At this time I had my lunch there at weekends also. The club was then more than half empty and the steward would say to me every Saturday, “You’re not in the country this weekend?”, a tease which palled on me well before it did on him but the balance was adjusted by an unexpected event. One day he came across to my table and in a reverent voice said, “The Secretary of State would like to speak to you on the telephone”. I was as surprised as he was but concealing this asked where the telephone was – in a booth just inside the front door. It was indeed the Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations, Patrick Gordon Walker, who wanted to speak urgently about the looming Nigerian crisis to the Secretary-General who was at his cottage in France. I gave him the telephone number and walked back to lunch marvelling at the efficiency of his staff who could track me down even at lunch at the Travellers.

Another nearby London institution that I loved as much was the London Library on St James’s Square, founded by Thomas Carlyle and others to provide the most extensive possible range of books for borrowing. As with a club you had to be proposed by two current members and it was like a club in the shabby comfort of its surroundings where there were always authors taking notes at the tables or reading in the armchairs scattered around the rooms. Its generosity about lending ran far ahead of any other library. A total of ten books could be borrowed at any one time and kept as long as you wished. If any other member asked for one of these books you received a courteous postcard enquiring if you had finished with it. The only slight eccentricity was that the Library bought only one copy of a book and never updated its holdings, so that when I sought to read Machiavelli’s Discourses I was given a handsome and no doubt valuable early eighteenth century edition.

When we were together we lived a rather domestic life at home. My lengthy absences, especially in central and southern Africa as Arnold battled to hold the Commonwealth together, meant that Julie and I needed to catch up with one another. We were also poor, or as poor as people living in Knightsbridge and keeping a nanny could be. We had little spare cash, which discouraged plays and visits to the opera and even sightseeing in the countryside. When I returned home we would occasionally go to Selborne to Gilbert White’s house and garden and lie in the grass eating a picnic lunch and talking, or go to Chawton to do the same in Jane Austen’s shadow – a practice which added Jane to Sophie’s names. Otherwise there were occasional semi-professional jaunts like going to Oxford to stay with David Fieldhouse, my old history tutor, and give a talk at Balliol on Southern Rhodesia where I was fiercely attacked by an elderly woman and a bishop walked out.

The round of receptions, dinners and national days also left me reluctant to give up free evenings to go to concerts, even at Wigmore Hall. Instead I acquired a square piano. These, built between 1790 and 1820, were a homely version of the early piano, an oblong mahogany box on four slender legs with a keyboard along part of one side. A dealer in Kent had a room full of dusty and jangling relics acquired from country houses that he restored to polish and playability. They had the advantage that, though lacking the power of later pianos, they fitted comfortably into the sort of house where we lived. This was perhaps the source of the fable that the Victorians were so prudish they felt obliged to cover the legs of their pianos. The legs of my piano risked a graze every time the door into the drawing-room was opened and I was tempted to cover them too.

An unexpected benefit of being in London was that Christies began wine auctions. They had a system which was like betting at the races but with a much more attractive return. They sold a number of bin-end lots for wine merchants who wished to dispose of the last two or three cases of a consignment, some of it still in bond and thus duty free. I would telephone to enquire about the likely price of a particular lot. They would give their estimate, at say ten shillings a bottle, and I would put down a bid of eight shillings. Most of these bids were never heard of again but over time they produced a surprisingly cheap range of the best clarets and burgundies I have ever drunk, stored in the old coal cellar which ran out under the street.

This success, as so often in life, led to over-confidence. A hogshead of Portuguese rose came up and Paul Cotton, a colleague at the New Zealand High Commission, and I were the successful bidders. A hogshead was too big to get into our houses or to bottle ourselves but even when done professionally with new bottles and corks we had twenty-six cases at a total cost of one shilling a bottle. I doubt we could have bottled water at this cost but even so it was over-priced. The wine would have disgraced a bar in a Fernando Po slum. We quickly came to an understanding not to serve it to each other. Glumly aware of the row of cases in the hall, we tried mixing it in sangrias, cocktails and cooking but in the end the only advantage of its cheapness was that we could abandon half the cases.

Entertaining, building links with Commonwealth diplomats and British civil servants, was an important part of the job as it was through all of my professional life. Lunches at the club were one method but we mainly relied on dinners at home, where Julie’s cooking and conversational skills made a considerable difference. That our house was so close to the West End made it easy to find us, though one New Zealander, the eccentric Quentin Baxter, telephoned us in despair at having spent half an hour searching for the address only to be told he was in a phone box less than a hundred yards from the house.

Well over a hundred dinner parties in the course of our four years in London gave a smoothness to the operation which the occasional lateness (two hours in one case) and other eccentricities of guests did not disturb. On one occasion a furious argument started over the Vietnam war which ended in a guest pushing back his chair and stating that it was impossible for him to stay. Unfortunately or perhaps fortunately the chair struck the cat which howled piteously. After all the bustle of soothing the outraged animal our guest resumed his chair quietly and the dinner went on.

The most memorable night was in fact a tragedy. Among the guests were an American couple. The wife, Emily Kitzinger, was a beautiful and charming East Coaster whom Julie had got to know and we thought it would be a friendly gesture to include them in a dinner party. They were late and while Emily was taking off her coat upstairs she collapsed speechless on the bed. The other guests had started on their first course downstairs and so the evening split into two halves, with Julie, the husband and a doctor worked to revive Emily while I, striving for a calm I did not feel, tried to manage a normal dinner for the other guests who were unaware of the drama upstairs. Emily spent the night in our bed while Julie and I slept on couches in the drawing-room. In the morning the ambulance men managed the ticklish task of getting her gently down the narrow stairs but she died in hospital a few days later.

After that we took a holiday, the only time we did in Britain. The house was in Cornwall above Talland Bay and not far from Looe. Talland Bay had a sandy beach and the children paddled and made sandcastles while Michael Fowler, the future mayor of Wellington who stayed with us for a time, sketched them in water-colours. It rained frequently as in most English summers then, but this if anything only enhanced the air of Celtic remoteness which still clung to the countryside. The secluded valleys had a number of small churches dedicated to rather dubious saints, like St Neot, who had swum to Ireland and back on an altar stone. Most of them had a holy well nearby, misty relics of the Celtic reverence for water. There was even an ancient rock, with an inscription in illiterate Latin to a ‘Marco’, which may have been the tombstone of King Mark of Cornwall and was itself a melancholy memorial to the last gasps of a moribund culture.

While we were soaking up this atmosphere I was telephoned by the police to say that our house had been burgled. We lost an opal brooch that Julie’s grandmother had given her, a pair of old candlesticks and Sarah’s Irish silver christening mug but, in what could only be called a silver lining, the ornate teapot which I had given Julie as a wedding present was left standing in full view on the bench, passed over perhaps because it had not been polished and looked like dull pewter. Our police were from the Gerald Road station, hitherto famous for its meticulously maintained window boxes of vivid flowers. They were equal to this challenge. A sergeant and constable turned up at our door a week later and when young Gerald opened the door to say, “Have you caught the gurglars” he was delighted to hear that they had, two young men called Brown and O’Halloran from Ireland. I gave evidence at their trial but of the silver and opals there was no trace.

After two years we took some weeks of home leave but timed it to coincide with the Secretary-General’s first official visit to New Zealand. Julie and the children went ahead to stay with her parents in Christchurch. It was the first time Caroline and Gerald had seen anything of New Zealand and their appearance in the local newspaper with a nanny and Gerald wearing a tweed overcoat and bowler hat more suited to Hyde Park struck a decidedly exotic note. Summer days spent digging for pipis at Akaroa and being spoilt by two sets of grandparents meant they acclimatised quickly, as did nanny who discarded her uniform and enjoyed drinking a gin and tonic with everyone in the evenings.

Coming later with Arnold I had the slightly odd experience of travelling as an official guest in my own country. New Zealand liked the Commonwealth and Arnold was invited to speak in all the main towns. By then I had given up writing speeches for him since whatever I laboured to put down he always gave the same rambling talk wherever he went.

We travelled down the North Island from Auckland, a rather exotic sight ourselves. Stopping for lunch in Taihape I took Arnold into the hotel to show him a little kiwiana. The bar was full of men in black singlets enjoying a lunchtime beer, with rifles and dogs propped against the wall. This, however, was not felt to be as unusual as the appearance of Arnold in the doorway with a flowing black coat, stick and large hat. The astonished bar fell silent except for a voice at the back saying “Christ!”

He went on to Australia while I had a few more days in Akaroa. We returned to London as a family, with the future Sophie on the way. The journey seems to have been mainly a series of memorable events for the children. In Perth, where we were delayed by the aircraft breaking down, I was bitten on the bottom by an irate black swan, the recollection of which could be guaranteed to produce helpless mirth. In Mauritius, blessed with glorious beaches, nanny lost the bottom of her bikini in the undertow and the two older children still remember the interest with which they gathered to see how she was going to handle this contretemps.

In Nairobi we stayed at a comfortable old hotel and, perhaps conscious of the thickening English atmosphere, nanny quietly resumed wearing her uniform. We drove through the nearby game park to see giraffes, a hippopotamus and a pride of lions where the baby Sarah, conscious of approaching teatime, said firmly, “Yeave doggies now”. Bernard Chidzero, a most able Zimbabwean forced out of his country by tribal politics, invited us to lunch. We got out of the car he had sent for us to be greeted by a handsome grey German Shepherd. With panicked cries of “It’s a wolf” the children leapt back into the car and shut the doors firmly. It took some effort to coax them out again. This led me to wonder, not for the first time, whether fear of wolves and snakes had somehow been imprinted on those of northern descent.

A few months later Sophie was born at King’s Hospital in Dulwich. It was an auspicious start, delivered by the Queen’s obstetrician, Michael Brudenell, and supervised by Sir John Peel, a man so grand that he toured the hospital in the morning, clad in short jacket and striped trousers and accompanied by a reverent entourage which included even the formidable matron. He asked Julie how she was, nodded, and was not seen again.

St Mary’s Cadogan Street was called upon for the christening after the baby, originally Catherine after a girl to which young Gerald was attached, had already turned into Sophie. It had by then become something of a family church to which the children and I walked every Sunday, keeping a careful eye on them in the pew for furtive disputes and inopportune giggling. In later years the fact that Sophie was allowed to bring a picture book to solace her during Mass caused and apparently still causes a little resentment that the others were permitted no such distraction.

Her arrival made it clear that we had run out of bedrooms and needed a new house. A family with four children under six years of age was not likely to make the heart of a landlord leap. A house at 36 Drayton Gardens came on the market, let by a general who had commanded the Commonwealth forces in Borneo during Confrontation and was now leaving to head the British Defence Mission in Washington. The house in South Kensington meant I could no longer walk to work but it was one of a handsome row built in the 1830s, had five floors, a garden for the children and a garage for the car I was hoping to buy. It was worth at least a try.

Sir George Lea opened the door. Hearing from my voice that I was a New Zealander he asked if I had known John Mace, “the best officer I had in Borneo”, and by a fortunate coincidence I had once shared an office with John. He ushered me into the drawing-room and said, “You’d better have a sherry”. We chatted amiably for some time while I sought an opening to raise the discouraging subject of my family. Then Sir George said briskly, “Well, if you’re going to take the house I suppose you’d better have a look round” and that was that.

The house and garden were large enough for the children to get away from their parents and the mews at the back was quiet enough for football and other games to be played on the road. Friendship bloomed with two neighbouring children, Ivan and Camilla, but for some reason it did not last. “We are broken friends”, Caroline announced. Before that, though, we had a joint fireworks party in our garden, memorable for me because I lit a rocket which soared straight towards an open window in our neighbour’s house. I watched in horror until to my great relief it struck the edge of the window and fell into the garden.

The two eldest slept at the top of the house under the roof and in the evening it took rather noisy trouble to bring Julie or I up five floors from the dining-room. There was the time when Sarah fell and gashed her forehead in the course of some illicit game. We discovered her being smuggled into the bathroom while hasty repairs were being carried out by her siblings. The gash in fact required to be stitched after a trip to St George’s Hospital at Hyde Park Corner.

Departing friends left us with a cat, Paddington, who caused the girls’ journey down the stairs in the morning to be punctuated with shrieks. He liked to hide in the curtains on any of the three landings and pounce with delight on the little toes showing under a nightie. He had lived his life in a house in the district from which he took his name and all this time had relied for calls of nature not on the open air but on a box of kitty litter in the kitchen. Once when we had been away all day at Ascot we returned to find him waiting at the garden door in some discomfort to scramble down the stairs to his litter box with great relief. At some time, though, Paddy must have crossed the cat mafia that ruled Drayton Gardens and he became increasingly nervous. On winter nights, as we sat by the fire in the drawing-room upstairs he lay with his eyes fixed on the windows that looked on to the street. His fears were apparently justified; one day he simply disappeared.

Sophie inhabited the room on the ground floor which looked directly on to the street. It was also the children’s room, with a TV, beanbags and toys scattered around. It could never be entered in bare feet from the risk of treading on pieces of Lego or worse. Sophie had a large cot at one end from which she quickly learnt to stand to look at the TV or the interesting activities of her elder siblings when they came home from school.

At the back of the ground floor was a bedroom usually occupied by one of the floating population of visiting New Zealand girls who replaced nanny Alison. When Julie’s parents came to stay with us we gave up our bed and dressing room (ornamented with photos of Pam Lea taking the jumps at Poona) and moved downstairs to sleep in this room. There I had an oddly vivid experience. I was wakened in the middle of the night by someone playing the piano in the drawing-room above us. Thinking I must be dreaming I looked around and saw the dim blue square of the window looking out on the garden. The music continued to play, Chopin I thought but unfamiliar – hearing it months later on the radio it turned to be the G minor posthumous nocturne. Though coming from the drawing-room it was not my square piano; the heavier sound was rather that of a mid-Victorian cottage grand which needed a tune. The pianist was not especially skilled, playing rather hesitantly and having the same trouble that I would with the long opening trill. The effect was of someone desperately unhappy. After listening for a time I leant over to wake Julie: “Do you hear the music?” This took some effort and when she was at last awake the music had stopped. But hearing the nocturne years later still gives me a shiver.

In the spring of 1969 Arnold offered us the use of his country retreat in the Dordogne. With a legacy he had bought an abandoned hamlet whose name, Aux Anjeaux or Where the English Are, testified to its medieval origins when the Plantagenets ruled Acquitaine. Of the handful of ruined cottages he restored two and a barn around a courtyard shaded by a spreading oak. He left the interiors as simple as they had always been and the stone staircase leading to the bedrooms upstairs still had no railing.

The only requirement of our tenancy was to smuggle the car boot full of liquor into France to replenish Arnold’s cellar. There was a ticklish moment facing the customs inspection when we drove off the car ferry at Cherbourg but the official leant into the open window on Julie’s side, touched his kepi respectfully and waved us through. Then, with a carful of children and Jo, our last New Zealand farmer’s daughter, all crammed into the back seat we drove south, a pleasant drive except for my tendency when navigating a roundabout to emerge on the wrong side of the road. We stopped for the night at an elderly hotel in Tours which was a gem of nineteenth century provincial decor, featuring wash-hand-stands and tall walnut armoires, and outside an enormous chestnut tree laden with white candles that glowed in the twilight.

The first thing that happened at Aux Anjeaux was that Caroline got lost. She wandered off to explore, claiming to have counted the lampposts to find her way home. It might have worked but after some searching Julie and I found her at a neighbouring farmhouse holding court in the kitchen surrounded by ancient ladies in black cooing over “la petite Carolina”.

Our market town was Fumel and our expeditions there to buy food were always fun. It was not just the bread and Perigord cheeses, or the Bergerac and Cahors wines, the latter the blackest of any wine I have known. It was the lamb. A leg fattened by grazing on the salt marshes and costing almost its weight in gold dust was unlike any we had tasted. Once home I urged farming relatives to oversow their paddocks with rosemary and other herbs to reproduce some of the flavour of the Dordogne lamb, a suggestion which provoked much hilarity. The treasure and speciality of Fumel, though, was an elaborate tart “aux milles feuilles” made from alternating thin leaves of apple and pastry with cinnamon and other spices. Because it took more than a day to make it had to be ordered in advance and because the telephone (‘allo, allo’) was difficult we resorted to ordering the next as we took delivery of the current one.

My mangled high-school French was no difficulty in these commercial transactions. Dordogne was rugby country and as a fellow citizen of ‘les tous noirs’ I enjoyed some reflected esteem. The Fumel butcher while wrapping the lamb liked to talk at length about the game, so volubly that my own comments were limited to ‘Oui’ and ‘C’est ca’, hoping that these had been inserted at the right moment. When I said goodbye at the end of our stay he complimented me warmly on my command of French.

In fact my shaky hold was tested severely when Julie and I were invited to a Sunday lunch by a woman who had been the mistress of the surrealist Max Ernst and who lived in a petit chateau nearby. We were late because the car wouldn’t start and arrived to find a very smart party of which every guest was French except us. The conversation was vigorous but whenever I carefully assembled a suitable contribution I discovered that the talk had moved on by two topics. The main subject was very French or rather very haut bourgeois. General de Gaulle had called a referendum on his performance. Everyone at the lunch table wanted him to continue but everyone agreed that they would have to vote against him to avoid encouraging him too much. He lost.

The woody countryside around us, dotted with chateaux and villages and shaped by the winding river Lot, encouraged excursions. A favourite of the children was the abandoned chateau of Bonaguil whose tall medieval ruins featured what must have been one of the world’s longest lavatories, running down three or so stories to empty into the moat and still showing the stains of ancient use. With Jo amusing the children Julie and I were able to go further afield, even to Carcassonne whose old towers and walls had lost a little credibility from over-enthusiastic restoration but where we lunched with pleasure at the Hotel du Terminus on the traditional cassoulet. .

Most sunny days were spent in the fields around the cottage, with leisurely wine and cheese lunches under the spread of the tree in the courtyard. Rain meant noisy games of Monopoly in the house which lasted most of the day. Nights were still, disturbed only once when the rickety pinnacle of chairs assembled by Sarah and Sophie to reach the biscuits in the old stone oven disintegrated with a resounding crash when they tried to use it.

The journey home down the Loire Valley to Le Havre was marked by a growing impatience with sightseeing and increasing warfare in the back seat. By the time we reached Amboise where I wanted to see the chapel where Leonardo da Vinci was buried in 1519 Julie and I had to take it in turns to rush up the slope to the chateau while the other kept a mutinous peace in the car.

A few months later I had completed four years at the Commonwealth Secretariat and returned to the New Zealand foreign service which posted me to Washington. I received an unexpected job offer from the Economist Intelligence Unit which Sir Bernard Fergusson was horrified to hear I had declined. “You should stay here, there’s nothing for you at home” was the frank advice of our former Governor-General but I did not want to become an expatriate and was even a little homesick for the view of Wellington Harbour from our Wadestown house.

We handed the Drayton Gardens house over to my successor, also a New Zealander, David McDowell, and spent the week of the moon landing in a hotel in Chipping Camden before embarking on the France for the voyage to New York, accompanied by the MGBT which I had bought with a legacy from my Aunt Edie. Julie was already unwell which we put down to the labour of packing and leaving the house but the five-day voyage was to be much more troublesome than either of us knew.