The Hensleys at Large

My paternal great-grandfather, Joseph Hensley, arrived in Dunedin on the Derwentwater in 1861. Dunedin was then just beginning its fifty years of growth, aided by an early goldrush, which made it the most prosperous city in New Zealand. A few years later he married Caroline, herself newly-arrived. There may have been some earlier understanding, both came from Devon and both spoke with a West Country accent all their lives – her husband always calling her “Carrlin”. What he did for a living is now lost but he must have prospered modestly. I have a hand-coloured photograph, still in its solid wooden frame, of the house where Caroline lived when widowed, a comfortable villa with a large garden featuring a tall cabbage tree.

My grandfather, also called Joseph but always known to his grandchildren as Bantan, was born in Dunedin in 1869. His childhood has been reduced to a thin string of stories he told about himself. For years I had a school prize of his, the unreadable story of those prigs “Sandford and Merton” which he claimed was the only prize he ever won, for attendance, since he lived opposite the school and could leave home when the bell began to ring and be in his seat when it stopped. On another occasion, coming home with a billy of fresh milk, he decided to test the existence of centrifugal force which he had just learnt about at school. He resolutely whirled the open billy round and round above his head and sure enough the milk stayed firmly in the billy but, he said sadly, he must have missed the end of the lesson because the problem of bringing the full billy to a stop proved insuperable.

Another story bridged the century. As a boy he met an old man who told him he had grown up in an English village. On a wet night in June, when he was four years old, his parents came upstairs and lifted him from his cot and held him to the steamy window running with rain which looked down on the high street. He heard the frantic blaring of a posthorn and past the house at full gallop went a coach drawn by six black horses, glistening with sweat and rain, and around each straining neck was a laurel wreath. It was the mail coach with the news of Waterloo.

Grown up he became a young businessman in Dunedin, even featuring with a photo in Wise’s Business Directory in the 1890s as an up-and-coming man (it occurs to me that he could have paid for it). In the early 1890s he married one of the numerous Frapwell sisters, Mary Barbara, always known as Molly. He claimed that he was so nervous when he first called that he greeted her father with “Good Frapwell, Mr Evening”. It was a marriage, familiar in those days and perhaps always, that featured endurance and acceptance of married life than any great pleasure in one another.

They moved to Invercargill when my grandfather became manager of the Southland Silver Beech Company, an enterprise dedicated it seemed to cutting down and milling every one of the slow-growing beeches that grew in the province. His workers could make furniture that was practical without being notably beautiful. I have beside me as I write an occasional table of an unconvincing eighteenth century design but sturdy enough to hold a pile of books. Of the furniture made as a wedding present for my parents in 1929 I still have two beds and a chest of drawers of the classic ‘Queen Anne in front and Mary Jane behind’ design but the face of the drawers, gleaming like flame mahogany, shows what could be done with the wood.

He had a comfortable two-storied house on Tay Street. In an older and now less fashionable part of town there is a Hensley Street but no sign that he ever lived there. For nearly forty years he had a succession of four collies, called either Laddie or Caesar. They were plagued by Bantan’s parrot who learnt to imitate his whistle and according to my father laughed when the dog hurried in. Each day the dog accompanied Bantan to the office and stayed with him all day. So my grandfather was disbelieving when an irate fishmonger called to complain that the dog was stealing his fish. He pointed to the dog sleeping soundly under the desk. Next morning, though, he kept an eye on the dog which got up quietly and stole out to the fishmonger’s which as common then had a tiled open front on which the fish lay on beds of ice. The dog neatly took one, retired to eat it and then slipped back under the desk as quietly as he had left it.

The love of Bantan’s life was not his wife but music. He played the organ every Sunday and every year conducted a performance of the ‘Messiah’ of which he said he could sing every aria and chorus from beginning to end. He was in demand as an accompanist at the recitals which were common as an after-dinner entertainment. I remember him saying to my father, “At the end a woman sang ‘Sink,sink, red sun’ and believe me, Len, when she had finished that sun was sunk.”

Religious differences, my father having committed the customary family sin of marrying a Catholic, ruled out family visits to Invercargill and so I never knew my grandmother’s house, though her commitment to good causes such as women’s rights and temperance did not suggest a notable level of comfort. I only saw my grandfather, who was cheerfully indifferent to rival creeds, when he came to Christchurch. Bantan had the entertainer’s gift of creating a symbol by which he was identified. Like Charlie Chaplin’s stick and Churchill’s cigar, he was the man with the pineapple. He always arrived with one at our house to the great excitement of my sister Alison and me, though where he found them at the height of the war when even bananas had vanished remains a mystery.

In the Square in Christchurch on one of these visits he came upon a harassed young mother with a young baby struggling to fold up a stroller so that it could go on the front of a tram. He stepped forward gallantly, raised his hat and said, “Allow me, madam”. He had the least mechanical sense of anyone in the family. After struggling fruitlessly for some time he stepped back, raised his hat again and said, “I’m sorry madam, I seem to have made it bigger”.

He liked on occasions to quote the sayings of an uncle of his, Uncle Louis. “Louie,” he would suddenly say, “did not read fiction because it wasn’t true”. Louie did, however, read newspapers because he pronounced them to be true. Over the years a whole raft of the eccentric sayings of Uncle Louie accumulated, on women, politics and even drink (he thought it healthy if drunk in the daytime), to the amusement of my father and in due course even me. Towards the end of his own life, my father could find no record whatsoever of an Uncle Louis in the family and came to the conclusion that Louie was an invention of Bantan’s, a helpful fiction which enabled him to make offbeat and even heretical comments on the life he was living.

My grandmother’s family, the Frapwells, also came from the West Country, from Great Elm in Somerset. They were a large clan, so large that I half-believed my father’s claim that they all lived in the elm itself. Like many in rural England they had converted to Methodism in the eighteenth century, abandoning the beautiful medieval church to walk to Frome for Sunday services. My great grandfather was Haroeh Frapwell. The Frap men all inclined to these mysterious names – Haroch, Heth and Hazo – which sounded vaguely Biblical but were hard to pin down. The girls got off more lightly with names like Hazel and Harriet.

Haroeh was a tailor, for which there was not much future in Great Elm, and he moved to London where my grandmother was born in 1868, at the surprisingly upmarket address of Chapel Street just behind Buckingham Palace. Perhaps he rented the basement. Four years later he moved again, taking his wife and family of four girls and a boy to New Zealand on what proved to be the most memorable experience of their lives.

The Surat was a three-masted ship of about a thousand tons. The voyage of the usual three months seems to have been uneventful until at the beginning of 1874 the captain reached the New Zealand coast where in his twenty-five years of command he had never been before. He seems to have taken to drinking and had no useful charts of the South Otago coast where his ship ran on to a reef in broad daylight and a favourable wind. He got the ship off with no obvious damage but as it resumed its voyage up the coast towards Dunedin it began taking on water in a flow which continuous pumping by crew and passengers including some of the women could not stem.

The captain after drinking steadily had now completely come apart. When the Government steamer “Wanganui” came in sight he drew a revolver to threaten those who wished to hoist a distress signal and the first efforts by the crew to lower a boat were stopped by the first mate (with the prophetic name of Foreshaw) also waving a revolver. In the end a boat was got away, carrying the Frapwell family including my six-year-old grandmother, singing hymns as they pulled for the shore. The ship meanwhile was beginning to settle and the captain drove it on to the beach at Jack’s Bay near the mouth of the Catlins River. There the rest of the passengers were brought off and all were taken in by the local sawmilling community. The passengers had only the clothes they were wearing but there was no loss of life, the weather having been calm throughout.

A small coastal steamer took many on to Dunedin where the kindly inhabitants raised a fund to care for them. Their troubles, however, had not finished. The wreck was sold by the insurers where she lay for 7050 pounds, a large sum. By a quirk of the law, subsequently changed, the sale included all the passengers’ baggage. So the Frapwells found themselves starting their new life without any of the furniture, bedding and clothes they had brought with them. My great grandmother had the mortification a year later of walking down a Dunedin street and seeing her best lace-trimmed sheets on someone else’s line.

The story was told and retold down the family and colourful details like the captain waving his revolver and his reliance on a pocket atlas seemed like the dramatic improvements that always accumulate on oft-repeated family tales. My father was especially sceptical about the loss of the baggage, legally impossible by the time he studied admiralty law. So all the descendants were astounded when research published by the Otago Daily Times in 1978 revealed that every detail was true. Even so there was a feeling that the story, like the ship itself, should be laid to rest. As Bantan said to my mother, “Tui, I’ve had the Surat.

Grandpa Haroeh was by all accounts quietly pleasant; my father remembered him as a white-haired old man beaming down at him as he filled his pipe. His wife, Louisa (nee Gowan and also from Great Elm), was more formidable. She was a devout Methodist (it must have been a trial that Haroeh’s farmer brother, Hazo, also ran the Eagle Inn at Great Elm). She was given to improving any occasion with an appropriate tag, a favourite for her grandchildren being, ‘wilful waste makes woeful want’. Her piety led my five-year-old father to ask her if she had known Jesus. She took great offence and ladies fluttered around him in disapproval saying “You’ve upset your grandmother”. This irritated my father to the end of his life: Jesus was old, his grandmother was old, what more likely than that they would have known each other. Grandma Frapwell fortunately died before her grandson took up with the Scarlet Woman of Rome, though she might not have been surprised at such foolishness.

She had five daughters, the second eldest of whom, Helena (“Auntie Lena”), married Uncle Fred and moved to Christchurch. They and their descendants all settled in Riccarton, in a cluster of streets just off Deans Avenue, perhaps in a folk memory of Great Elm. When they went into town to shop or take afternoon tea they took the train, walking to Riccarton station and taking the train past Addington to Christchurch. Perhaps clothing or propriety made it impossible to make the short walk across the park as all their descendants did.

For years in one of those streets a cabbage tree stood, and I hope still stands, which was being planted when the news arrived of my father’s birth in 1903. He liked to keep an occasional eye on this coeval, not difficult since he often walked past on his way through Hagley Park to his office, and enjoyed asking companions to try and guess its age. I remember his remarking, running a hand through his own hair, that the tree was getting a bit thin on top.

Uncle Fred was a man of firm and rather testy views. At dinner one evening his wife suggested he have a little more and he declined. She pressed him more than once – “Fred, you’ll have a little more; Fred, just to finish the pot” – until he turned to her and put an end to the domestic dialogue: “Mother, I thank you, No.”

He has come down to history with one magnificent gesture. Their house, now a motel, had a back garden with Fred’s special treasure, a large asparagus plot. One morning in spring it was coming to full splendour when the butcher’s boy came in his pony-cart to deliver the meat. He dallied somewhere and did not tie up the pony adequately. It wandered over to Fred’s vegetable garden to graze, pulling the cart back and forth over the asparagus plot.

My great-aunt discovered the devastation just before Fred returned home for his lunch. With great tact she met him at the gate and silently took him round to the garden. Fred stood there for a moment, taking in what had happened, and then he stepped forward and with his walking cane methodically beat down every stem of asparagus left standing. Then he turned and went in to lunch.

The youngest daughter, Emma known universally as Auntie Pem, was what my father called “the pin-up girl of her day”. She was still handsome in her old age and had great charm, not a notable feature of the Frap world. I met her and Cappy her old black Labrador only once, for afternoon tea at her house overlooking Dunedin harbour, and wished it was more often.

The eldest was Harriet, born in London in 1864, ahead of Helena and then my grandmother. She was always known as Hattie or simply Auntie Hat. She was almost completely deaf and Hat could be more easily shouted. My father would bellow “Hello Hat” when she arrived at our house and she would reply, with the gentle smile of the deaf, “Yes, isn’t it” or something similar.

She had been married to Thomas Holgate and they lived on Maori Hill in Dunedin. Uncle Tom, like Uncle Fred, is now remembered solely for a single misfortune. At the back of the house there was a short row of outhouses including a pantry, storeroom and coalhole. Auntie Hat liked to go about her work singing tuneful and cheerful hymns from the Moody and Sankey collection; I remember “Stand up, stand up for Jesus” and “When the roll is called up yonder I’ll be there”. Coming down the path thus occupied she noticed that the coalhole door was open and gave it a lusty swing shut as she went past. Unfortunately Uncle Tom was inside filling the household coal scuttles. The slam of the door not only locked him in but it also blew out his candle. Shouting and hammering on the door were useless given his wife’s deafness. Four hours passed before she noticed his absence and unlocked the coalhole door to free him.

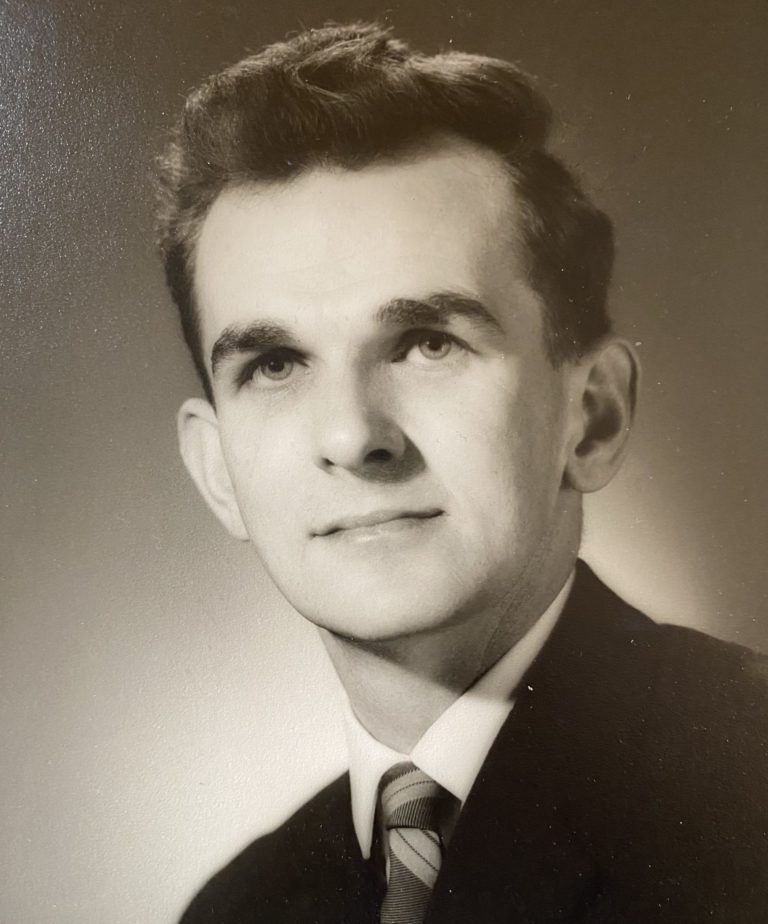

Auntie Hat’s deafness was of long standing, possibly congenital. In my time she wore a rather ugly black hearing aid which enabled some sort of conversation. Before that she had a large ear trumpet which she called “her instrument”, instructing my father, “Bring me my instrument, Len”. They were fond of one another. She looked after him when he was at John McGlashan College in Dunedin and when he finished his schooling at Southland Boys High in Invercargill, emerging with a gold medal as dux, she took him off to my grandfather’s house on Stewart Island for a break.

Bantan’s business ventures tended to the optimistic rather than the practical – an investment in the Rise and Shine goldmine which neither rose nor shone, and the acquisition of land at the back of Oban which he laid out in paper streets, Winifred and Leonard Avenues, after his two children. All that eventuated was a holiday house in the bush. They made the uncomfortable journey there on a small tugboat and on their first night the house caught fire. My father was woken by the crackling flames but his aunt of course could hear nothing. He managed to wake her and get her out through the smoke and the flames but nothing else could be saved and he lost his newly-won gold medal.

What my grandmother thought about a life in Stewart Island is not known but she disliked the Invercargill weather, “a climate fit only for beasts”. As a grandmother she was pleasant to us without being particularly affectionate on the occasions when she came to Christchurch to stay with her daughter, Winifred, who lived at the foot of the Cashmere hills. She was not naturally child-minded and domestic life did not especially interest her. She had two children, Winifred and my father Leonard, nine years apart and according to my mother (not a disinterested witness) she cried throughout her pregnancy with him. The Leonard for whom he was named was the Rev. Leonard Isitt, a close friend and father of Sir Leonard Isitt, a famous airman and founder of Air New Zealand.

Hymns were the only music that held any interest for her and she lacked a sense of humour. Being married to Bantan must have been something of a trial for that alone. On one occasion they stopped at a Chinese laundry to pick up my grandfather’s shirts. The shirts could not easily be found in a large shelf of them behind the counter, all labelled with a small Chinese character, until my grandfather spotted his own and pointed them out. The owner was surprised and said, “You know Chinese?” “Yes,” said my grandfather, “foleign missionaly” and there followed a warm exchange of mutually unintelligible courtesies. My grandmother was shocked: “Joe, you deceived that poor man”.

Her life in Invercargill revolved around the church, good causes and a band of like-thinking women friends. Sociability consisted of afternoon gatherings in each other’s houses which, husbands complained, could often go on to the early evening. Since cards (“the devil’s playthings”) and sherry were out of the question, they clearly enjoyed lengthy conversations. On one occasion the editor of the Southland Times, known to my father as Papa Joyce, came home for dinner to hear the buzz of talk still going on in the drawing-room and a note telling him that his dinner was in the oven. In a gesture worthy of Uncle Fred he took it out of the oven and poured it down the sink. Years later the story was repeated to me by my grandmother as an example of the baffling nature of men.

Her causes had earlier included votes for women, though less because of a keen interest in political equality – she did not believe that men were the equal of women – as that women could more effectively fight the battle for temperance in Parliament. Drinking was a serious issue in the colony, as it was in most of the settlement colonies including Australia, Canada and the United States. Men worked hard on the land all day and in empty landscapes found little to do in the evening except drink. Pubs were not places of sociability as in England but places to drink away the monotony of existence.

So religion and need combined in the Women’s Christian Temperance Union of which my grandmother was an enthusiastic member, organising and speaking at innumerable meetings. My father, in knickerbockers and blond ringlets, was enlisted as a poster boy for the cause. He had signed the pledge to abstain from alcohol at least three times by the time he was nine. He also treasured a collection of temperance songs, rousing and eminently singable like the hymns of the period. My favourite was “Behind the Swinging Doors” where little Benjamin goes back and forth from the saloon to persuade his dad to come home before his sick child dies. He is of course unsuccessful but not before we have sung the memorable line, “Through the smoke and the haze sat Dad in a daze”.

The campaign came surprisingly close to success. In a 1919 referendum Prohibition was carried in New Zealand but a resourceful government declared that this could not be confirmed until the troops returning from the war had voted. Auntie Lena’s son was one of them and he reported that when the vote was taken on his troopship the result was along the lines of 999 for Continuance and 1 for Prohibition. The chaplain hastily excused himself and my cousin said that the rest of the voyage was taken up with the hunt (unsuccessful) for the person who had voted no. There were more dissenters than that suggests; of the 40,000 returning soldiers 32,000 voted for Continuance but that reversed the result.

The compromise on Prohibition was to allow individual electorates to decide for themselves. Invercargill immediately went “dry” and remained so for years, to the great satisfaction of my grandmother and clearly many others. The nearest pub was in Wallace, some distance away. But in the weekend many fathers who had a car liked to take an airing and the Wallace hotel claimed to have the longest bar in the world.