How Will a Self – Absorbed NZ Face a Rising China?

“You may not be interested in war, but war may be interested in you.” Leon Trotsky

Like most countries, New Zealand has a basic foreign policy framework based on geography, language and the cultural links that go with it. The atmosphere, the feelings around this basic policy can change with generations or with fashion but a major departure from it is both unusual and difficult to sustain. In the eighties a long period of peace led to some resentment at what was seen as a dependence on our traditional friends. We abandoned our security arrangement with the United States and declared that henceforth we would pursue an independent foreign policy. In the midst of peace this caused no measurable damage to our security but for the next twenty-five years successive governments, including the Prime Minister who had led the revolt against the ANZUS alliance, laboured constantly to restore, not the alliance itself, but the comfortable relationship that had earlier existed with the US.

The concept of the independent foreign policy remained. In speeches by politicians it was often emphasized as a fiercely independent foreign policy but what this upwelling of nationalism meant in practice was never defined. In the beginning it was code for dislike of any link with American foreign policy. As time passed and no new friendships or policies appeared it came to look more and more like our old foreign policy with an added nationalist flavour. After a period of excited rhetoric the basic policy framework simply reasserted itself.

What has faded away, though, is much interest in foreign policy itself. In the last two decades New Zealand has become preoccupied with domestic concerns and has withdrawn from much interest in the world. Unlike most countries, ours is an island state separated by a thousand miles of sea from even its closest neighbours and so without the difficulties and the stimulus provided by neighbours. In a time of settled peace and no serious threats, therefore, we have slowly drifted away from an interest in the common security. Embassies and residences have been sold. The foreign service has lost much of its experience and has lost standing even at home. The current Foreign Minister also held the apparently more senior portfolio of Local Government and when this was lost she sank as purely Foreign Minister to the bottom of the Cabinet rankings. New Zealand is not the Hermit Kingdom laughed at by the British press but the joke is no longer as absurd as it once would have been.

Our security is still tied to Australia’s but as the long peace has endured we have given up carrying our share of the common defence burden. Australia’s size and geographical position means it has to spend on defence. New Zealand’s geographical position means that it can opt out of this basic requirement provided Australia does not. In the past it was largely accepted that our defence forces should be able to work together since any security threat would in practice be a threat to both. An attempt was even made in the nineties to formalise this as CDR, Closer Defence Relations, but it was stillborn as successive New Zealand governments spent less and less on keeping our defence up to date. The combat navy was reduced from four to two frigates and a very favourable deal to lease F-16s from the US was overturned by the incoming Clark government, leaving New Zealand with no combat aircraft at all. The outcome is that Australia no longer sees New Zealand as a reliable defence partner.

Ambivalence about working with both the US and Australia seems to have drained the energy from other aims of our traditional foreign policy. Geography means that South East Asia is our most important neighbour after Australia and its stabilisation preoccupied us throughout the sixties, seventies and beyond. The outcome was probably the greatest success of our foreign policy since the war. We helped Malaysia and Singapore achieve a successful independence and, though the long war for South Vietnam was a tragedy, the equally long involvement of the US saw the war end, not with the domino fall of the region to Communism as Mao Tse-tung and many others expected, but the emergence of the prosperous and confident alliance of ASEAN countries.

We now seem to have lost much of our earlier interest in these countries. What used to be a flow of ministerial and other visits has shrunk to a trickle. Where we were once a credible supporter of the region’s security the steep fall in our defence capabilities makes this a courteous memory for regional governments but of no present relevance. Neither our government nor the press have much to say about events in South East Asia.

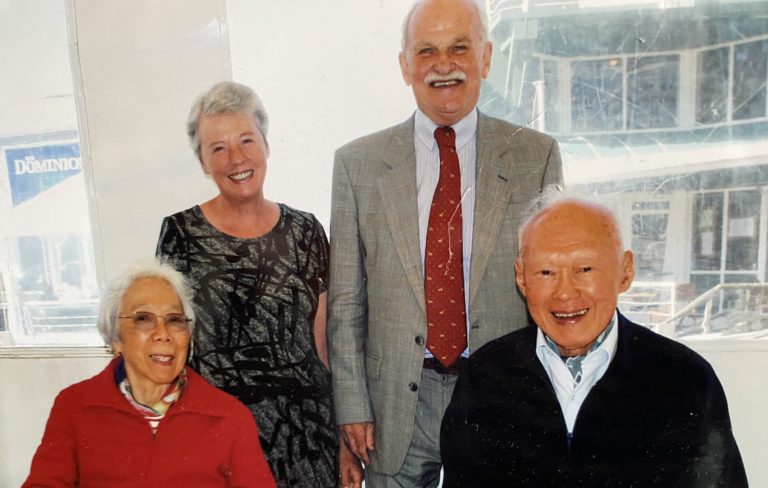

The region is prosperous and still stable but for countries like Vietnam and the Philippines a new security worry is taking shape. No-one in ASEAN is under any illusion that it will have to find ways to adapt and acknowledge the rising power of China. Understandably, though, they do not want to be left to manage this on their own. They want to be sure that America will stay to balance the new power and they believe that Australia and New Zealand can greatly help with this, as they did in the sixties. Lee Kuan Yew liked to say that the two countries anchored ASEAN’s south but when pressed he would add that their influence was important in keeping the Americans interested in Asia. Australia with its rearmament plans will be able to do this more than ever but New Zealand, self-absorbed and wrapped in isolation, has dropped out.

It is an unpleasant fact, particularly for a nation devoted to peace and uncomfortable with arms, that influence with neighbouring countries depends, not on calls for peace and disarmament, but on how useful our help will be when their interests are threatened. Frederick the Great, not an encouraging model for those peaceably inclined, said that arms were to diplomacy what instruments were to music. He was right, not because diplomacy should always be aggressive – China’s aggressive nationalism is imposing heavy and rising costs in its foreign relations – but because assurances to your neighbour about how much you value their well-being and interests are empty when you have no capability to help them if there is trouble.

China’s aggressive nationalism is the first time we have had to face even the possibility of war in the region in over sixty years. There are precedents for the difficulty of fitting a newly-confident great power into an international system used to working without it. In the 1890s the newly-unified Germany became obsessed with overtaking Britain and longed (and rearmed) for Der Tag when it would. In the 1920s Japan threw off the shallow roots of democracy and embarked on a nationalist crusade to become the paramount power in Asia.

Both these endeavours ended in tears. The parallel with China does not make such an outcome inevitable but it is a reminder of what is at stake if China or we misread what is at stake. The precedents unfortunately do not give us very useful clues on how to better manage aggressive nationalism in a great power. The usual murmurings of more and yet more diplomatic effort do not provide any convincing evidence of success. Of course we must ‘keep the channels open’ and keep talking with China. Of course we must lose no opportunity to try to understand their outlook and show our goodwill and desire to meet their reasonable needs but talking rarely eases nationalist resentments.

It might, where the problem is a misunderstanding of each other’s aims, but China’s aim to become paramount power in the Asia-Pacific and perhaps beyond is repeatedly proclaimed by its leader and by its actions over a decade. As the differences deepen we have to keep in mind the risk that the urge to rest our hopes on diplomacy will confuse and distract us from the core of the difficulty. Totalitarian states with complete control of their own public opinion have learnt to use our free press against us, dangling hopes of peace talks, walking away and then resuming them in ways that mesmerise the Western press and its readers while they steadily pursue their aggressive objects.

Like the Kaiser’s Germany, also a continental power, China has begun to spend heavily on its armed forces and especially its navy. It has seized and fortified the chain of islands down the South China sea, it has torn up the international treaty guaranteeing Hong Kong’s freedoms (throwing away the hope of a peaceful reunion with Taiwan as it did), it has brawled with India on their Himalayan border and begun a series of escalating provocations of Taiwan’s borders, prior to its proclaimed intention of taking the island by force.

These actions, reinforced by China’s ‘wolf warrior’ diplomacy to punish countries like Canada and Australia, have understandably had a dramatic effect on China’s standing in the world. While it followed Deng Xiaoping’s instruction to ‘bide its time’ China became prosperous and a pre-eminent economic power a step away from overtaking the US and becoming the world’s largest economy. Far from building resentment this peaceful expansion was marvelled at and universally welcomed. Countries vied for closer links, with New Zealand priding itself on being the first to conclude a trade agreement and having no difficulty with China becoming our largest trading partner, as Britain once was.

All this turned over when Xi Jinping became leader. We can only speculate how long a powerful China would have continued to bide its time but Xi abandoned it dramatically for a rush to make China feared in the ancient way by ‘all under heaven’. The cost to China’s foreign relations has been enormous. Every country in Asia and the Pacific has become nervous of China, knowing that a word out of place or even taking tea with the Dalai Lama can lead to serious loss of trade. This may be pleasing to Xi’s aim of restoring China as the ‘Central State’ but many countries including New Zealand are already looking quietly at reducing their trade dependence on China. A quasi-alliance, the Quad, has sprung to life as a check on Beijing’s ambitions and the surprising diplomatic reversal is that along with the US, Japan and Australia, it includes India. A number of other countries like South Korea and the Philippines are starting to consider what they would do if Taiwan were attacked and the whole region, except New Zealand, is rearming.

All this looks like a disastrous Chinese departure from the normal standards of a peaceful, non-violent foreign policy, but to think that it unduly worries President Xi is to miss the point. His policy is not to make or keep foreign friends, it is to place China at the top of the foreign policy ladder. Trying to do so imposes costs and he is willing to accept them up to a point. The point at which the costs may become too high is not when China is cold-shouldered abroad or when it is not invited to conferences but when an alliance begins to emerge that is capable of checking his dominant ambition, taking Taiwan.

The need to avoid a war over Taiwan looms larger and larger. We are seeing the horrors of modern war in Ukraine and there is no reason to suppose it would be different for the 25 million Taiwanese. Like Ukraine it would not be a brief takeover but a prolonged struggle, not simply because Taiwan is preparing to defend itself but because we know already that at least the US and Japan would help defend it. If China was successful it would become the predominant power in the Western Pacific, US influence in the region would disappear or be greatly diminished, the ASEAN countries, no longer able to balance Chinese with American influence, would find themselves sitting uncomfortably in China’s lap and Australia and New Zealand would learn again why a free ASEAN matters to them. If China did not succeed it might well face an internal upheaval. In either case the damage and brutality of a war between well-armed powers would be huge and felt for a long time.

So, to borrow a phrase from Lenin, what is to be done? The threat of war would galvanise the diplomats – that is what they are for – but a diplomatic solution does not seem possible unless China is willing to abandon its aim to annex Taiwan. In this situation the weaponry of diplomacy, the ‘usual modalities’ in UN jargon, will not be very helpful. Passing resolutions, calling for peace conferences and collective complaints (within the prudent restraints of trade policy) and even sanctions are all of little help measured against China’s cherished long-term aim. Words, as so often in diplomacy, will fail us.

That leaves us with force, an indecency rarely said aloud in policy analysis. The prospect of failure will clearly play a much larger part in Xi’s consideration of an invasion than its effects on international opinion. His friend’s unhappy experience in Ukraine may have given him pause for thought. He may have already totted up the risks and decided to wait for a more auspicious time, one when the West is less on its guard, to attack Taiwan. We don’t know, but it seems reasonable to conclude that the best answer to Xi’s challenge is to raise the risk of defeat. The more other countries stand ready to defend Taiwan as they have defended Ukraine the less likely the careful Xi is to go to war. Perhaps the Romans were right – to stay at peace we need to be ready for war.