Reflections on a Volatile World

The difficulties we face today, when we can for the present see no solution, inevitably seem worse than those neatly packed away in the past. This is especially so of the world beyond our borders. Our forebears hardly thought of foreign affairs except when the prospect of war loomed. Now the troubles of the world are followed in great detail by the media. Every uprising and outbreak of violence round the globe is brought to us in often horrifying detail by television and radio. The worst excesses of lawless humanity and of natural disasters are set before us live and in vivid colour by television. It is hardly surprising that we are left with the impression that the world is becoming increasingly volatile and violent.

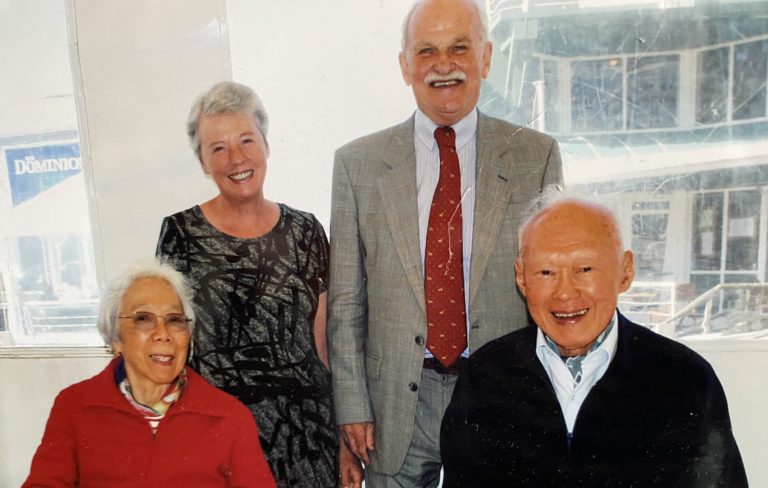

Yet I wonder. Viewed away from the headlines the prospect seems less daunting. I have spent a working life of over half a century in international affairs and in that time have seen a train of crises and worries come and go. I have emerged from it all somewhat sceptical of the more alarmist claims about the future. Many years ago a British diplomat who had joined the Foreign Office in 1910 said at his retirement gathering in 1950 “In all the years of my service I have constantly heard reports of the likelihood of war. It has been my practice invariably to ignore such warnings and I have only been wrong twice.”

That may have been carrying a relaxed attitude too far but it may be wiser, or at least more cheerful, than the tendency among many foreign analysts to think that the world is becoming progressively more difficult. Diplomats tend, like insurance adjusters, to acquire a rather low view of human nature. Concentrating on a succession of crises for which there is no immediate solution encourages a cautious if not gloomy outlook. Working on stubbornly intractable problems can feel like rowing a heavy boat over a long distance with the wind and tide against you. In these circumstances I sometimes found it salutary as a foreign service officer to pause and look back at the distance already covered.

Dr Johnson recommended that we should “Let mankind with extensive view survey the world from China to Peru” and when you do look back it is surprising how far we have travelled even in my working life. When I joined the foreign service in 1958, cheese in this country came only as ‘tasty’ or ‘mild’, olive oil was something you rubbed on your chest, phones took two years to be connected, overseas travel was difficult and it was common to talk of the coming World War III.

Now we are in the midst of the Long Peace, the longest period in modern times without a major war, we have seen off the two major totalitarian threats to our way of life, the international institutions we helped establish at the end of the Second World War are less broadly supported but they are well entrenched and they have presided over an extraordinarily peaceful end to colonialism and an equally extraordinary expansion of world trade and wealth. Hundreds of millions of people have been lifted out of poverty. The number of those living in extreme poverty continues to fall steeply, by 130,000 a day every day since 1990. Medical advances have been equally dramatic. In 1960, 181 of every 1000 children did not live to five, now less than 48 do, a reduction of almost three-quarters.

Nuclear weapons are still a worry. Their abolition does not seem a likely prospect under the present system of nation states but although we were once assured that a nuclear holocaust was a matter of ‘when’ not ‘if’, we have devised shaky but so far effective ways to live with them. And frightening as they are, their existence may be underwriting the continuance of the Long Peace. If we found a way to abolish nuclear weapons without also covering conventional weapons, we would simply be turning the clock back to 1939 when the great powers could wage wars of aggression and the big divisions could again roll across the frontiers. That is one worry that is no longer on our list.

Of course, thinking of what has gone well in recent decades does not wave away the serious international worries we still face and the risk that some of them could go badly wrong. Even the most optimistic diplomat knows that human nature does not change or, as Dean Rusk, an American secretary of state, put it, “At any moment two-thirds of the human race is asleep and the other third is awake and in many cases up to some mischief”. Our capacity for making mischief is very great. Look at the internet: an unalloyed benefit when invented but within a few short years human ingenuity had come up with viruses, trolling and financial scams, and it now looks like becoming the battleground of a new Cold War in cyber-space.

The list of potential troubles we might face is therefore of indefinite length, stretching as long as you wish to look for trouble. Among the more plausible are the risk of new disease pandemics, a collapse of the world’s trading and financial system, food and water shortages, religious wars and even perhaps an asteroid strike. The important point about this dismaying list is that they are possible not actual. They are future risks and it is reasonable on our past experience to hope that human ingenuity will cope with most of these possibilities. As it did with the horse manure problem. Throughout the 19th century London’s use of wheeled transport was growing rapidly. In 1894 an editorial of The Times predicted that by the middle of the next century the streets of London would be 9ft deep in horse manure. An alarming thought but the arrival of the internal combustion engine ensured that this never happened. This brought problems of its own but the wheel of fortune, or rather of technological change, has turned again and we can now see something which would have seemed impossible to our parents, the approaching end of the petrol-driven motor car.

Instead of looking at what might or might not go wrong in a more distant world, it seems more immediately useful to look at some of the problems likely to preoccupy us in the coming years. New Zealand’s small size and geographical remoteness means that these present worries may affect us less directly than larger countries but mishandling them will still affect our prosperity and security and we will be using our influence in the world community to help manage them as sensibly as possible.

The first of these concerns is great-power rivalry in the Pacific. The United States and China, the world’s two largest economies and now the two largest military powers, are inevitably rivals. Since 1945, the balance of power in the Pacific Basin has rested on the hitherto unchallengeable power of the United States Navy. Now that balance is beginning to shift. China is building aircraft carriers and powerful new destroyers, signalling that it intends to create a blue-water navy able to cruise anywhere in the Pacific and beyond.

That is natural in a rising great power and does not necessarily indicate aggressive or expansionist intentions. China now has world-wide trade routes and like earlier major powers it feels the need to acquire a long-range navy to help protect them. It is however one sign of a deeper problem: how to fit a huge new power like China into an international system which it had no part in designing. It may not feel the commitment of those countries which established the current system and have been managing it for seventy years.

This is a risk which understandably worries the historians. It goes all the way back to the Peloponnesian War which Thucydides tells us broke out “because of the rise of Athens’ power and Sparta’s fear of it”. The record nearer our own day is not much more encouraging. Germany at the end of the 19th century and Japan a generation later felt that the established international system was unwilling to make room for them and the result in both cases was a world war. It is even more unsettling to learn from Professor Allison of Harvard that out of 46 rivalries between rising and status quo powers over the last 500 years, only three have been settled peaceably, and two of these was because of the danger of nuclear weapons.

So there is clearly a great risk if the rise of China is mismanaged, or if Chinese nationalism turns sour and aggressive. The gleam of hope here is Professor Allison’s calculation that two of the three peaceable resolutions was the result of fear of nuclear war. The mushroom cloud which hangs over Chinese-American rivalry may paradoxically be our best chance of beating the historical pattern. Both countries have long had a nuclear arsenal, both are well aware of the enormous dangers they represent. It is reasonable to assume that whatever irritations accumulate, whatever jostling there is over the South China Sea, Taiwan and other disputed territories, both will be careful to keep their differences well below the mushroom cloud.

That may not be so persuasive in the case of the other and more reckless Asian nuclear power, North Korea. Its excitable talk of attacking Japan and the United States regularly takes the headlines but the danger may be less than appears. The unpleasant regime in North Korea regards the acquisition of nuclear weapons as essential to its survival. It feels that only the ability to threaten the United States can give it the ability to deter any effort at regime change and perhaps negotiate something better with Washington. For Pyongyang, as with older nuclear powers, deterrence not use of the weapons is the only policy that makes sense. Having achieved a nuclear capability and being close to acquiring the long-range missiles that could deliver them, it would be suicidal use them to go to war with the United States. That would guarantee the very regime change they are determined to avoid.

The United States, China and Japan, the three powers entangled with North Korea, have found themselves unexpectedly powerless. China holds better cards than anyone else, since the North Korean economy depends on its oil and other supplies. It has so far been reluctant to play them, however, for fear of overthrowing the regime and bringing American troops up to its border. For the United States and Japan piling on the rhetoric and the sanctions has provided some emotional relief but little else. We seem more likely to face a prolonged and irritating stalemate than a hot war.

The second of our present concerns about international stability is mass migration and the Mediterranean is its present focus. Distance has confined it largely to the television news in New Zealand. Even the boat people passing through Indonesia to Australia in small craft have so far found it too risky to reach New Zealand. But the great and growing numbers flooding across the Mediterranean from North Africa, Somalia and Ethiopia for the moment look unstoppable and the humanitarian efforts to save drowning and stem the flow have seemingly turned naval and other rescue vessels into more reliable means of ferrying the migrants to Europe.

What began as the flight of refugees from instability and religious violence in the Middle East has gradually turned into a surge of economic migrants. Once the way had been opened up and the European Union shown to be open to large-scale movements, more than a million people, usually young men desperate for the opportunities for the jobs and better life that Europe offers, have swelled the tide. It shows no sign of lessening and the President of the European Parliament has recently warned of an exodus “of Biblical proportions” over the next five years. The scale of this problem is one which only the Roman Empire has faced before and the outcome then was not encouraging.

No-one has foreseen let alone prepared for population movements on this scale. The initial response was uncertain, for Europe like America has traditionally given refuge to the dispossessed. But faced with such an exodus the nation state has revived within the European Union and elsewhere and is seeking to protect itself. Walls have come into fashion. Former President Trump’s aim of building a wall to keep out economic migrants from Central America has been ridiculed as both expensive and ineffective. Others however are turning to it at least as a first response. Macedonia has built a wall along its Greek border, Lithuania is fencing off its border with the Russian enclave of Kaliningrad and Norway is building one to close its Arctic frontier with Russia.

In recent decades forty countries have built walls against sixty neighbours. The nation state, once viewed by the hopeful as being in decline, has revived with the call for tighter borders, as has the unpleasant nationalist and shrill opposition to foreigners that can go with it. Borderless travel and the globalised economy, seen as inevitable developments ten years ago, are coming under pressure. As hitherto tolerant societies have felt the weight of increasing immigration on their language, beliefs and way of life, the resentment of incomers has grown. The welcoming words of the Statue of Liberty about welcoming the huddled masses of the poor have begun to look odd to many Americans. The European Union has so far battled in vain to defend its supranational ideals against rising nationalist discontent in Germany, France, Italy and Eastern Europe members. Britain left the Union to recover its sovereignty, but so far has had little success in controlling immigration. Economic migration, the unexpected revenge of the poor on the prosperous world, is likely to be with us for some time.

The freer movement of people has also contributed to the third of our present worries, terrorism. The distinctive feature of terrorism is that the victim is not the target. Those killed by his bombs or gunfire are not the target of the terrorist. He is aiming at a cause, a government or the structure of a society. It is a weapon of the weak who feel they have no other recourse. Its effect depends not on the isolated killings terrorists achieve but on the publicity they get. Acts of terrorism spread uncertainty and fear far beyond any physical reach they could have. Terrorism is the unwanted child of the media. The growth of our news and social media and the vivid photographs and videos they display have greatly increased the effect of terrorism and thus have inadvertently increased the horrors they condemn.

Historically, though, terrorism over the past century has not been very successful in overthrowing governments. Movements like the Basque ETA or the IRA in Ireland attract followers, develop the organisational skills to kill hundreds and then fade away into criminal or fanatical fragments and end up apologising for their misdeeds. I had some direct experience of it when shots were fired into my house in Washington in 1973 by the Black September group of Palestinian terrorists.

The epidemic of terrorism, by fanatical Islamists, is rather different. It too seeks to dramatise the powerlessness of infidel governments to protect their people but its ambitions, its scope, goes way beyond those of previous terrorist groups. The successive Islamist movements are a new combination of classical terrorism and religious war. The number of their potential recruits and sympathisers is therefore very large. Britain has 23,000 of its own people on its watchlist and the numbers will not be very different in the other countries of Europe and North America. The aim of these numbers is equally large, not just political change in someone’s national territory but radical religious change over a large part of the world, particularly that part once described as Christendom.

This ambition is impossible but in the fervour of a religious revival it is likely to inspire recruits for some time yet. Earlier forms of nationalist or separatist terrorism could be relied on to fade in the face of a society’s resistance but a movement which takes its justification from the express word of God in the Koran may be more durable. In the meantime the risk can only be managed and governments and their intelligence services are getting better at managing it. Major atrocities involving conspiracy are vulnerable to interception. It may be that the more recent sequence of acts by individual terrorists are signs of weakness, in that bigger attacks are harder to organise, but no intelligence however efficient can prevent these single and suicidal acts and the resulting publicity still spreads fear. The vast majority of us are as unlikely to encounter terrorism as to win a lottery but managing the outrage it causes may be more of a challenge. People who may be target of religious-inspired terrorism will demand stronger measures to prevent or reduce its occurrence. Cool heads are needed to ensure that these measures do not permanently damage our civil liberties.

The last of these present discontents is climate change, a problem so large and difficult that we still cannot agree on what to do about it. Almost everyone now accepts that climate change is well underway even if we do not know the extent of the disruption or precisely how it will affect our societies. Global warming has been measurable since the beginning of the 19th century, a natural recovery after the little ice age that afflicted the globe for the previous five centuries. Industrialisation and especially population growth have accelerated this trend. The core of the problem is not that we like to drive to the grocer’s or fly to somewhere warmer for a holiday. It is the growth of the world’s population which has increased since 1900 from 1.6 billion to its current level of over 8 billion and continues to increase at present by nearly 2% a year. These are all people who breathe out carbon dioxide and need to cook, be clothed and be heated.

There is little that we can do about this. Taking the bus, turning down the heat and all the other worthy measures recommended “to save the planet” is of little relevance at this scale. The earliest warnings about the change recommended radical politics, a kind of Puritan socialism where everyone wove their own clothing, walked to work and avoided any industrial manufactures. However difficult the change may be, only political dreamers saw any benefit in returning to the Middle Ages.

Despite the serious risks of a warming climate such as a dramatic rise in sea levels, the public has remained unmoved, reluctant as Burke said to overturn familiar institutions upon a theory. International conferences have regularly discussed the evidence, targets have been set and missed, promises have been made and not kept. It has become clear that whatever the risks no government, democratic or otherwise, is prepared to make the level of change required for serious improvement. When predictions fluctuate among scientists and lobbyists the developed world is unwilling to take costly action and the developing world is still inclined to see it as a rich countries’ problem. The citizens of the world, or at least those who do not see it as a matter of religious belief, seem to have silently decided to sit this one out, or rather adapt to the changes when their nature and extent becomes clearer.

In each of these four present worries, there’s no immediate or even foreseeable solution. The future of any of them could go in one of several directions. Each has alarming implications and all are frequently the subject of even more alarming books. Pessimism has a field-day with problems for which we can for the present see no solution. But the challenge of seemingly insurmountable problems has faced humanity from the beginning and we are here in greater numbers than ever. So I am cautiously hopeful that human ingenuity and resilience will overcome these difficulties, as in the past we have overcome plagues and famine and institutional slavery.

There is however a final danger to keep in mind. A volatile world can be made more uncertain by hasty responses. Where complex problems require careful thought to work out a sensible response, the most dangerous volatility may be our own. We have a new difficulty in the mass emotion that can be flashed up by social media. De Tocqueville thought that the calm management of threats might be more difficult for democracies but even he could not foresee the rise of the Twitter mob. The issues raised by climate change or how best to deal with mass migration are not best managed by demonstrations and spur-of-the-moment solutions. As the long-established post-war balance begins to shift we are going more than ever to need fuller public discussion to help insure us against hasty reactions.