A Visit to Kathmandu

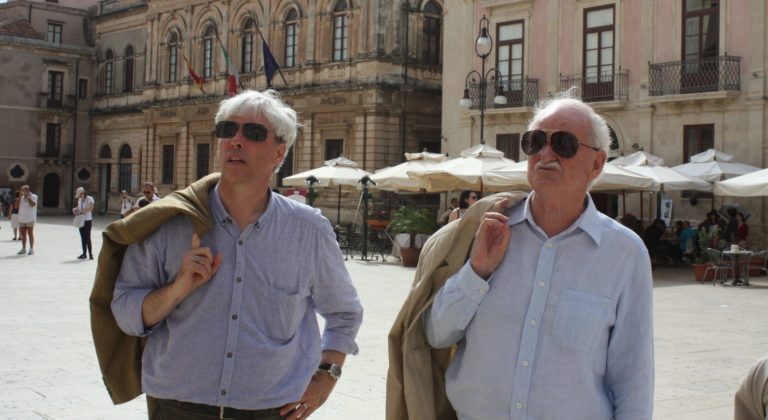

We left Dhaka in what was then East Pakistan in the early morning, flying on Royal Nepalese Airlines. I was accompanying the Commonwealth Secretary-General, Arnold Smith who had been invited to visit Nepal to discuss the possibility of Commonwealth membership. We flew in an elderly turboprop past the dazzling white peaks of the Himalayas, looking out the window as we passed Mount Everest with a long plume of snow blowing from its summit.

We were the only passengers and the sari-clad stewardess spent her time cooking a meal for the flight crew. When she walked up the aisle carrying plates of a delicious-looking curry, the Secretary-General stopped her to ask if we could join in and she returned to the galley to cook some more. It was indeed delicious and still ranks as the best meal I have ever had in an aircraft.

As soon as we were settled in our hotel we were summoned to meet the Foreign Minister, who had invited us to explore the prospect of membership. He was English-educated and most hospitable but there was not much to explore. The Commonwealth had attractions for a small country sandwiched between India and China but membership might disturb the delicate balance Nepal was maintaining between the two giants. These facts were quickly agreed in the talks, and indeed had been perfectly clear before we even came, but the visit had perhaps been arranged to build a little goodwill and also to signal to its neighbours that the country had other options. Anyhow our visit was arranged for several days and after that we had nothing to do but sightseeing.

With a car and a young foreign service official we spent some time touring Kathmandu’s pagoda-like temples, whose eaves were often decorated by vivid carvings of Tantric deities engaged in vigorous sexual congress. The variety of positions demonstrated was surprising and possibly included the legendary position known only to the Emperor of China. Some were too dark even for Arnold’s busy camera.

Then we were taken to pay our respects to a living goddess, the Kumari Devi, a young girl who lived in isolation as a divine reincarnation until her first loss of blood, whether by menstruation or a cut, destroyed her purity and she was replaced. We entered the small courtyard of an ancient palace and after an appropriate wait a child of eleven or twelve years, dressed in scarlet and with face and hair heavily made up, appeared at a grilled window. We bowed respectfully and then looked up at the window. The child sat motionless regarding us gravely for a time and then withdrew. Our young guide claimed that her demeanour signalled good fortune for us; had she coughed or frowned the omens would have been very bad. As a foreign service officer myself I thought that the omens could probably be arranged. Otherwise it would surely have been too risky to bring state guests to an occasion where a sneeze might ruin the visit.

The afternoon was spent in a visit to a jeweller because Arnold was looking for a large emerald. The Kathmandu jeweller sat cross-legged on the floor of a shop that in bazaar fashion was open to the street. He talked of white and pink sapphires and other stones I had never heard of while unscrewing dirty twists of papers and pouring glittering little waterfalls of the stones from one hand to the other. He produced an emerald as big as my thumb which Arnold regretted not buying for the rest of his life. Then he opened a piece of ancient rag and produced a double-strand necklace of small, uncut but polished emeralds interspersed with shining baroque pearls from the Gulf. It glittered in the afternoon light. I could immediately see it on Julie but, as uncertain as Arnold, I weighed it up and down in my hand until the jeweller, invoking the age-old practice of sellers of rugs and precious stones, urged me to keep it overnight.

The Foreign Minister was giving a formal dinner that evening and with some idea of safe-keeping, I slipped the necklace into the pocket of my dinner jacket. I was seated next to the Foreign Minister’s wife, a lively and beautifully-mannered lady who was clearly the product of an expensive English boarding-school. I suddenly thought what an excellent chance to learn whether the necklace was a good buy and fished it out of my pocket. Her face darkened and she looked at it with distaste. My grandfather was a Rana, she said, and these stones have been stolen from his headdress.

I had been warned by the Foreign Office in London to be careful in any comments about the Ranas who wore a distinctive headdress with dangling strings of small polished emeralds and had ruled Nepal under the King until their overthrow a few years before our visit. Their regalia had been looted and was now trickling on to the market. I was stricken with my clumsiness and apologised profusely. My companion cheered up: it’s a bargain she said, buy it. I did and it is now worn by my eldest daughter.

The next morning we drove to Pokhara not far from the Tibetan border where there were camps of Tibetan refugees in the fields. There was little international interest in their plight and they seemed to be managing a precarious living by relying on visitors to buy whatever they had brought with them. So I helped by buying an unusable Tibetan baby spoon, something called a demon-quelling knife and four little silver lamps that had held butter-oil to light an altar.

But the purpose of the trip was not to show us the refugees but the impressive new road the Chinese had built down from the border. Government officials we talked to were nervous that its purpose was military. Certainly there was little sign of normal traffic and even to my unmilitary eye the careful engineering, perfect surface and regular spacing of parking bays looked like something more designed to move a mechanised army than anything else. The fears though were unfounded: more than fifty years have gone by and the road has yet to carry a tank.

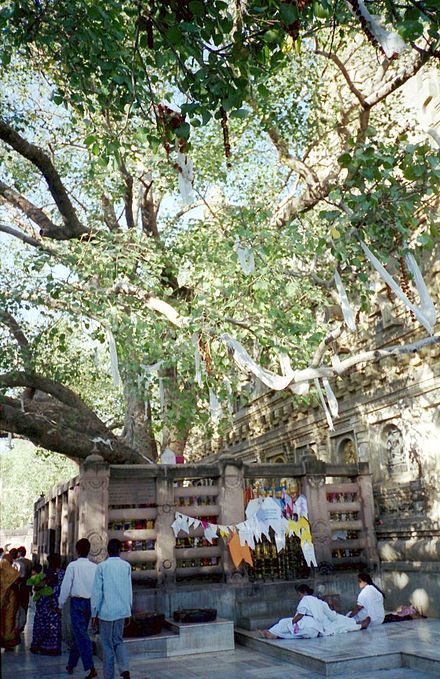

Religion was a powerful force in Nepalese society, but of a surprisingly tolerant kind. Tantric Buddhism of the strand developed in Tibet was dominant but Kathmandu had Hindu temples and the Kumari, uniquely, was a dual Buddhist/Hindu goddess. Beside the river there were burning ghats to cremate the dead with Hindu rites, though elsewhere in the mountains sky burial was still practised, where the dead were laid on high rocky platforms to be disposed of by vultures and other birds of prey – a practical answer to the problems of ground too rocky to dig and a scarcity of wood to cremate.

The temples we visited were of a fierce Tantric Buddhism and the incense-choked darkness seemed to give less weight to the traditional Buddha in repose than to images of snarling and grimacing demons. In the countryside the white-washed monasteries were more restful, with beds of flowers and lines of fluttering prayer –flags. On the flat roof of one several young monks, in the dried-blood colour of their Tibetan robes, were playing a series of what looked like Alp horns. Some were long – perhaps over seven feet – and one end had to be rested on the parapet while at the other end a monk of formidable lung power produced an echoing booming sound. Perhaps they had once sent messages and alarms like yodelling in Switzerland or perhaps they were simply intended to entertain the gods as the musical booms rolled round the sunlit valley.

On our last night we stayed in the British ambassador’s summer cottage high in the mountains above Kathmandu. It had been built sometime in the nineteenth century, a now rather dilapidated wooden bungalow with a pillared entrance in vaguely Greek Revival style. Little used it mainly housed an impressive population of rats. There was no electricity and the living-room was lit by the fire and by little oil lamps which created enormous and threatening shadows around us as the rats scuttled about in the dark corners.

It was built as a refuge from the summer heat in the valley but an early incumbent had spent lengthy periods there, away from the tangled politics of Nepal. The house could just be seen with a telescope from Kathmandu and the hermit ambassador was said to have communicated with two flags, one of which said “Send More Food” and the other “Send More Gin”.

Getting there required a long drive, spiralling up a rough road through hillsides with hundreds of narrow terraces curving symmetrically around the contours of the hills, the patient work of centuries. It was dusk when we reached the cottage. The valleys below were already in darkness and the mountain ranges in purple twilight. In front of us soared the mighty peak of Dhaulagiri still glowing gold against the fading blue of the sky. I stood in the chill of the mountain wind watching the shadow of night creep slowly up the mountain until finally only the high peak still burned bright and then was snuffed out. Then I went inside to the log fire and, appropriately, had a gin.