Dinner in Kyoto

In 1973 the world was in a difficult position. Inflation, a malign legacy of the Vietnam war, was already a worry when the oil-producing states in OPEC realized that market power had swung their way and imposed an embargo. The oil-importing countries including New Zealand faced a bill of $US 60 billion, the largest tax rise in history. The few who kept their heads argued that all cartels, even oil cartels, did not last. Most, faced with the severest slow-down since the 1930s, looked desperately for ways to mitigate the dangers.

Devaluation held an obvious attraction. One of Norman Kirk’s last acts was to announce a significant one but there was a growing fear that larger economies would be increasingly tempted to resort to competitive devaluations – the curse of the 1930s – in the hope of finding shelter and reliable supplies of oil.

Japan, resource-poor and with memories of its shattered post-war economy, was particularly shocked. They were scouring the world for oil and paying large premiums when they found it. Their sense of vulnerability seemed excessive. After all, unlike many countries (including our own) they had plenty of money to pay the new prices. They felt, however, that only skills and hard work had enabled them to rise from the wreckage of the war. Now it had, at least partly, to be done again and resource diplomacy, every country for itself, concerned them much more than the coordinated international response which countries like New Zealand were urging.

Frank Corner who had just become Secretary of Foreign Affairs and I, then head of the Economic Division, arrived in Tokyo to argue the case for a calmer response. We had little success. The Gaimusho had no interest in a coordinated response, especially as there were few signs of one, and their politicians had even less. We were wasting their time. The Gaimusho would never have even hinted at so uncourteous a thought: instead, they organized an elaborate tour to Kyoto and the temples around it.

I had been there before, but Frank had not seen Japan since he came with the Far East Commission (General Macarthur’s device for keeping the allies occupied) in 1946 and he was fascinated by the transformation. In Kyoto we enjoyed the bright summer gardens of the Katsura imperial villa and in a more severely Japanese style the garden of silvery moss and the gravelled one at Ryoanji monastery. We drove to a lonely valley in the nearby hills to a Buddhist nunnery clinging to a slope and surrounded by pine trees. It had been built by an unfortunate lady whose imperial husband had been murdered in front of her, only for his successor, her young son, to suffer the same fate. She built a moon-viewing platform and composed a poem which summed up her life: “How strange that I should sit here, watching the moon slip in and out between the clouds.”

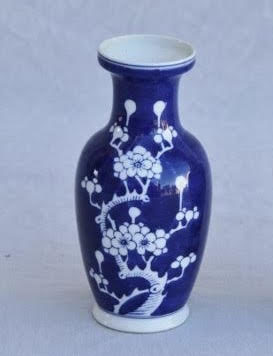

Our last evening was dinner at a traditional house, no doubt a regular stop on the Gaimusho’s tours. No concession was made to foreigners’ lack of flexibility. Unable to sit cross-legged, we knelt on the tatami matting and sat back on our heels as a series of dishes were brought in through the sliding, paper-glazed door by a girl in a kimono. The food, the lacquerware and the room had the restrained elegance that marked the best of Japanese style.

Frank had earlier been given something called cedar-barrel sake by the ambassador in Wellington and he was emboldened to ask it we could have some. The face of our host clouded briefly and then he recovered himself to say that some would be provided shortly. Out of a small window on my left I saw a young man racing off on a bicycle and in due course returning with a small barrel of sake in his basket.

Having ordered the barrel, it looked as if we would have to finish it or at least make a determined effort. This was not a difficulty, it was in fact delicious, and the meal with cups of sake wandered on for a very pleasant two hours until the kimono-clad waitress withdrew, and it was clear the dinner had come to an end. Unfortunately, it also became clear that we had sat so long on our knee joints that we could no longer get to our feet. After some experiment all that could be managed was to roll over on one side and then crawl.

If the household was surprised to see the shoji door slowly prised open and their two guests emerge crawling on their hands and knees like a pair of returning cats, they managed to conceal it. After we had been helped to our feet, we thanked everyone for an unmatched dinner and hobbled off to the waiting car.