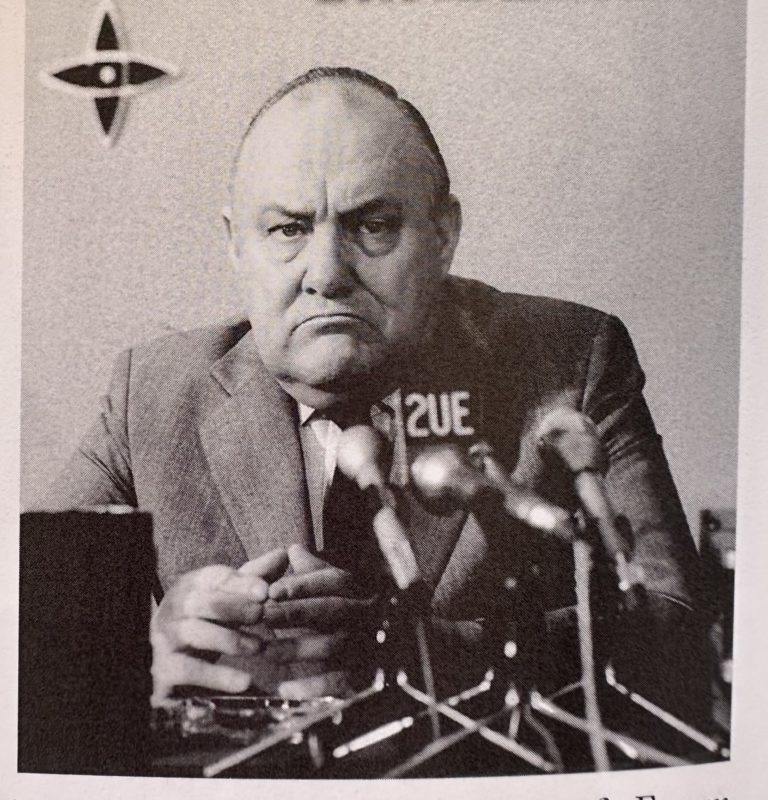

Lee Kuan Yew in New Zealand

From the early days of his political life, Lee had a liking for New Zealand. It is not easy to pin down the reasons for this fondness. It owed something to the fact that we were not Australia. He did not like Australians for equally murky reasons, though it may have gone back to that early morning in February, 1942, when he watched the defending forces march into captivity and was not impressed by the shambling walk of the defeated Australian troops (ill-led and ill-trained as they were).

Another reason that he liked to mention from time to time was that we were close to the United States. Given Singapore’s geographic vulnerability, especially during the rise of China’s power, he wanted to keep some hold on American help and felt that New Zealand provided a tripwire if there was trouble . But most of all he saw this country as helping to anchor Singapore’s southern flank. We were not too small to be helpful and not too big to be a nuisance, a solidly predictable friend that “did not jump about” in the words of his Foreign Minister but could be relied on if there was trouble.

He made his first visit to New Zealand as Premier in 1964. As he went from one civic reception to another, he said he never knew that a country could have so many mayors. Sitting on the stage during the speeches he was impressed to see from the rows of polished black boots how tidy our civic dignitaries were. He also had rueful stories of some of the comfortless hotels he stayed in, of chilly trips down the corridor to the bathroom and dinners that heavily emphasised mutton. But he loved it apparently and to the end of his life talked of the tranquillity of his stay in Christchurch, praising it as a perfect English cathedral city.

This may be a clue, because he had for years a romantic view of the English and this perhaps illuminated his rosy view of New Zealand. The first time I met him was when he opened Singapore’s new tourist office in 1976. I had just arrived, and had not even presented my letters to proclaim that I was officially there. When I joined a group clustered round the Prime Minister he greeted me with a disconcerting remark, “I was just saying, High Commissioner, that the difference between New Zealanders and Australians is that New Zealand was settled by the younger sons of gentlemen. Isn’t that so?” I swallowed hard and made the lame reply that some New Zealanders liked to think so.

Looking back, this may have been a little test. Perhaps, like Sir Robert Muldoon but much more courteously, he liked to bounce new arrivals to see how they responded. Anyhow I had no more challenges of that sort from Lee. It was a little deflating to be told the next day that the Prime Minister did not wish to receive a ceremonial call. This, however, was his brisk custom and no New Zealand High Commissioner from the first ever had any trouble seeing Lee whenever they asked. For what had cemented this goodwill was that at the painful time of Singapore’s divorce from Malaysia New Zealand had been the first country after Britain to recognise its independence. Both Lee and his deputy, Goh Keng Swee, told me more than once how bereft and isolated they had felt and how warming Keith Holyoake’s action had been.

The stresses of building up and securing an independent Singapore ruled out simply friendly travel and two decades went by before Lee’s early journey was matched by a visit from Goh as Deputy Prime Minister. After his cramped island Goh was astonished by the panoramas of empty land in New Zealand. He was a little disapproving of our slackness, saying to me that industrious Chinese would have planted all that green pasture in vegetables.

Lee himself returned to New Zealand only in the early eighties. This time he avoided running the gauntlet of the mayors by saying he wanted a holiday. Though he visited Wellington for talks with the Prime Minister and others, for most of the time he and his wife relaxed at Huka Lodge on the Waikato River and kindly asked if Julie and I could join them. So I had the pleasure, which I never could have afforded myself, not only of almost a week in the company of the Lees, but also of staying at a luxurious resort beside the dark, quietly-flowing river.

Breakfast the next morning got off to a bad start. When we came in to a sunny room filled with the smell of toast and eggs, the talkative host at the lodge, Harland Baker, proudly drew Lee’s attention to the sideboard overflowing with yellow flowers sent, he said, by a Chinese admirer. This seemed a harmless compliment but I noticed that Lee was upset. “Don’t you see,” he said to me, “this is to tell me that they know where I am.” I assured him that his security was being carefully guarded, suppressing my private doubts about whether the young constable with us, whose main function was to run with Lee every morning, could offer much protection. But the flowers were removed, calm was restored and there was no further disturbance.

Sightseeing around Taupo did not greatly interest him. We went to see the lake, about which he was mainly concerned to hear of the great volcanic explosion eighteen hundred years before. Neither boating nor fishing attracted him, and certainly not swimming. Most days he and I went for long walks down the river and through the scrub but he was no naturalist. When his attention was drawn to the manuka or the song of the grey warbler (it was September) his response was of good-mannered indifference. The pleasure of the holiday was clearly absence from government responsibilities, and the peace and good food was what he seemed to enjoy most. His tastes in food and wine were those of an educated Englishman. He did not care for Chinese dishes, “You never know what’s in them” he whispered to me.

Two years later he was back. On his way to the Commonwealth Conference in Melbourne he seized the chance for another break in New Zealand. He arrived in Christchurch and flew straight to Wellington where I met him. Being Lee he did not waste the journey but meditated on what he saw out the window. He said, “I looked down on those mountains and thought in fifty thousand years this country will still be here, whereas Singapore…” and his voice trailed away. Though he kept a tactful silence on New Zealand’s careless economics he felt that the country was so solid that it could afford a little carelessness.

After the necessary calls, and a combative TV interview with Ian Fraser, we flew to the Hermitage under Mount Cook, landing in what seemed to be a stony river-bed nearby. Lee, who had enormous moral courage, was physically inclined to be nervous. We met once by accident at Nuwara Eliya in Sri Lanka’s hill country and back in Singapore he complained to me about the tedious car journey down to Colombo, stuck (as often happened) behind an unyielding elephant moving at its own stately pace. But when I pointed out that the Sri Lankan Government had provided him with a helicopter, he said, “When you see how their cars are maintained, would you travel in a helicopter?”

So it was a measure of his trust in New Zealanders that he was entirely relaxed about flying around the country in a variety of aircraft. At Mount Cook we were flown up to the snowfield at the top of the Fox Glacier in a small plane fitted with skis. This seemed daring even to Julie and me. We splashed around happily in the deep snow but when the pilot said the weather was changing and he might have a little trouble getting off Lee was untroubled.

The Hermitage hotel gave proof that this trust was returned. We were late going into dinner and the dining-room was already full. Though there was no announcement that I was aware of, when the Lees came through the door the entire room rose to its feet and applauded. Whatever quiet pleasure this may have given the Prime Minister, he was brought down to earth by his wife, Lily, saying at dinner, “No ice cream for Harry because he was so hard on that poor young interviewer.”

The bush tracks around Mount Cook delighted him. We plodded along through the softly falling snow behind his indomitable parka-clad figure, from time to time stopping to admire the view or the circling keas which seemed as interested in him as he was in them. The weather, which had suddenly turned cold, was a joy to him. He claimed it was a genetic inheritance from his northern Chinese Hakka forbears and spent his whole life in a battle with the tropical Singapore climate.

A day later we returned to Christchurch to join the plane in which Sir Robert Muldoon was travelling to the Melbourne meeting. It was a grim journey. Muldoon had cleared the decks for war over the South African rugby tour and neither I nor any of his advisers could reach him. I have no recollection of Lee on the flight; perhaps like me he had sunk into invisibility.

A year or two later he was back for another holiday, a relaxation he clearly could not enjoy in Singapore. In what had become established custom he invited Julie and me to join them but this was not an official visit and he selected and paid for his party’s accommodation. From a careful search on the internet he chose a small country hotel, Braemar Lodge, on the Hanmer plains in North Canterbury.

We drove there from Christchurch without stopping. He had in fact grown disillusioned with his former love. He surprised the Commonwealth Conference in New Delhi by discoursing at some length on the earlier beauties of Christchurch, its gentle peace and courtesy. Now, he said, all that was gone; it was commercially dependent on tourism and with traffic so noisy that at night you could not sleep. When I remonstrated with him about my home town, he dismissed it saying, “You don’t live there any more”.

Because it was his own holiday he was accompanied by a small retinue at the lodge – two security men, a driver, a young woman secretary and a doctor, John Wong, an oncologist. From then on Lee was always accompanied by a doctor on his travels. He had inherited his charm and toughness from his redoubtable mother, Mamma Lee (Mrs Lee Chin Koon), and feared that he had inherited her unreliable heart as well.

She was English-speaking and of Straits Chinese descent who introduced Julie to the pleasures of peranakan or Straits Chinese cooking, some of which survives still with my daughters as does her own phrase when tasting the results – “verrry delicious”. She told Julie once that when a girl she had prayed to marry a European and escape the tyranny of a Chinese mother-in-law. But she was as strong-minded as her son and occasional remarks by her daughter-in-law, Lily, suggested that she did not entirely escape this charge herself.

With good medical care and unremitting self-discipline Lee lived to be ninety-one. He was quietly obsessive about exercise to the extent of irritating the sequence of medical advisers who travelled with him and who thought that he over-indulged. The bedroom next to his at the lodge was set up as an exercise room for him and passing the open door after lunch you would see the back of the Prime Minister pedalling vigorously on his stationary bike.

Outside the Lees’ bedroom at Braemar was an open hallway with a small bar built into the corner, inevitably known (but only to Julie and me) as Harry’s Bar. We acquired the habit of gathering there in the evenings for a pleasant drink before dinner. The lodge cooked what he liked best, plain New Zealand food, accompanied by his choice of French wines. His taste in wines was as traditional as his food. He was not deeply interested – it was what you had with a meal. He was happy to drink New Zealand wine when I ordered it but French wine had the cachet of being the best so that was what he chose.

My attempt at Braemar to widen his diet was an effort. I heard a rumour that nearby was the only place in New Zealand where porcini mushrooms grew wild. The next morning we set out, after a little reconnaissance by Julie and me, and found the mushrooms growing under a line of beech trees on an unmetalled road skirting the huge state pine forest. The excitement of gathering Nature’s bounty, whether apples, pine-cones or mushrooms, seized everyone and there were cries of triumph as the first mushrooms were found. Later when I straightened my back and looked down the grassy roadside I was struck by the surreal sight of Julie, Lily, and the Prime Minister of Singapore in floppy sunhats scrambling around in the grass to fill their buckets.

When we had enough I fired up the barbecue in a sunny corner of the Braemar garden and promised everyone a lunch of mushrooms on toasted buns, along with a little wine and cheese. Lee’s caution appeared. How knowledgeable was I about mushrooms, how could I be sure that these were not poisonous? My only defence was that I knew a porcino when I saw one and to prove it scooped and ate some from the grill. When as predicted I was still standing after five minutes everyone tucked in happily. They were such a success that the Lees took a bucket back with them to have at their hotel before they left for home.

That was the last of the holidays, after that our meetings were for lunches or dinners in either Singapore or in Auckland or Wellington when Lee came to New Zealand. He was at his best at the table where he relaxed and loved to talk. Unlike many successful politicians, he did not simply lay down his views. He had an endless curiosity and liked to explore any new topic. When I sent him a draft of the first chapter of Final Approaches his first comment was interest at learning that flying-boats have difficulty taking off from smooth water.

We argued amiably about juries, capital punishment, British membership of the European Union and the need to trust democracy and while I doubt his views moved an inch, he certainly enjoyed the process and could surprise. On one occasion he suddenly said, “Don’t you think the British gave up the Empire too soon?” I had to clutch my fork at hearing this from the man who had once presided over the burning of buses and tearing down pictures of the Queen, but it turned out he was thinking of Africa and that a further decade or two might have embedded better administrative habits.

When we once fell to discussing our view of ourselves, he said revealingly that he saw himself as a kind of District Commissioner, that official who had wide powers to rule over whole regions in the days of the Empire but who also had an equally wide responsibility to look after his people. I saw him (but did not say so) more as a Chinese Emperor which his manner often made him seem in Singapore, but with hindsight I think the District Commissioner was closer to what he aimed to be.

Only once in these visits, the last, did we get a glimpse of the imperious Lee. He and Lily, now in a wheel-chair, were on their way home and he invited Julie and me to have lunch with them at Shed Five on the Wellington waterfront before they caught the flight to Auckland. The High Commissioner joined us. A frail woman who said little and was clearly nervous of him, she was worried about their missing the flight. Lee felt he was being pressed to hurry his lunch and bullied her, making her more nervous than ever. Lily who might have stopped this seemed not to notice. The atmosphere was briefly unpleasant and I intervened to tell the Prime Minister what an excellent representative she was. The affair took only a few moments, but after we had ushered the Lees into their car I glimpsed the relief on her face, a look I realised I had frequently seen on the faces of other officials in Singapore

He was worth listening to about writing speeches, at least to anyone else who had faced this wearing task. When a major speech loomed, he said, he started by reading everything he could find on the subject. Then the books were put away. You had to “concentrate the neurons”, work out what should be said and then “simplify, simplify, simplify” until a clear text emerged that could be easily understood. It worked; this intellectual man could explain political and economic issues to large gatherings of people in Singapore and carry them with him. Any speech by Lee, even on minor social occasions, always had a point and was worth hearing.

With one possible exception. He became rather obsessed with the vexing problem that clever young men instead of marrying plain girls with PhDs were sadly likely to prefer girls with beautiful legs and no degree. One night when we were at dinner with him in his Wellington hotel room he held forth on this at embarrassing length until Lily leant forward and said, “Harry, you’re talking nonsense.” A little hurt, he said, “Am I?” but to the best of my knowledge never mentioned the subject again.

This certainly proved the value of marrying someone as intelligent as she was. Lee liked the company of bright women and if they were beautiful as well, so much the better. Whenever I wrote to say that I would be passing through Singapore he always enquired, “Will Juliet be with you?” and if so the occasion would usually be upgraded to a dinner. He enjoyed being teased by her. Julie thought he was a bit of a flirt, though in no way serious, and said she had to be careful that their agreeable flirting did not irritate Lily.

On another visit to Wellington, after dinner the four of us round the table fell to telling ghost stories. Julie told of the strange events when the baby Caroline was brought home in Samoa. Lee spoke of the night his grandmother died and the signs that warned him. I spoke of the woman who played Chopin one night in the room in our London house where there was no piano. At the end of the evening Julie said that despite all this she did not believe in ghosts. Lee leant forward and fixed her with a solemn gaze: “Juliet, do not discount the supernatural”. His reasons remain a mystery but there was no doubt that he became more aware of the spiritual as he grew older, exchanging the suspicion of organised religion natural to Chinese rulers for an unexpected interest in Christian prayer. This he never mentioned.

At these dinners he often talked about his early years in politics and the turmoil of the fifties when he and his colleagues struggled with the Communists for control of Singapore. The Communists had a large following in the Chinese-speaking Middle Schools and could mobilise large numbers of students and others to fight the police, block traffic and display their strength. It became clear from these conversations how well the British colonial authorities had played their hand in quickly seeing the young Lee’s abilities as a credible nationalist leader and backing him with great discretion. Their responsibility for security enabled him to build his political strength without ever looking like a British puppet.

Over dinner once in Auckland he told the story of his undercover meeting with “the Plen”. In the street battles of the fifties the prudent Communists had two levels of leadership. The public leaders who called for anti-imperialist demonstrations were liable to be periodically swept up in operations to which the British security forces gave names like Cold Storage. The real leadership stayed underground and unknown.

When Lee was either Premier or likely to become so he received a covert approach from the underground Party head proposing a meeting. Lee mulled it over with Goh and his closest colleagues and agreed to meet the shadowy man they nicknamed the Plen. Getting there required Lee to take a taxi somewhere, meet a schoolgirl who would direct him somewhere else and so on until he was in a featureless room in an unknown part of Singapore. The Plen turned out to be a cold-eyed young Chinese and the meeting, Lee thought, had been arranged so that he could gauge how serious a threat this new politician was likely to be. After half an hour or so Lee returned to his office by the same tortuous route to report on the conversation that was memorable only for having taken place.

What the Plen’s conclusions were we will never know but I asked Lee if they had ever met again. Yes, he said, in 1982 in Beijing where the Plen had taken refuge after he was defeated. Had he learnt the lesson? No, said Lee, he was as convinced as ever of the inevitability of Communist victory in Singapore, just that he had got the timing wrong and the triumph would go to someone else.

I was anxious as an historian that these stories should not be confined to the dinner table and pressed him for several years to write his memoirs. He was a speaker not a writer and was uncomfortable with the thought of the frankness that would be expected. I urged it as a duty (always a better argument with Lee): think how valuable it would have been if other founders of a country like George Washington had left a personal account of events.

When he gave in, he tackled the task with typical energy, recruiting large numbers of researchers, advisers and fact checkers, including me on one or two occasions. The first volume, the battle for Singapore, had all the drama of that struggle. The second volume, on Singapore’s subsequent rise from third to first-world status, naturally lacked that drama. It did not have the sparkle of Lee’s conversation and his preference for policies over personalities made it less exciting. Lee sent me the whole draft, saying that the publishers thought it too long and wanted 40,000 words cut. Could I suggest which 40,000 should go? This was a delicate business and I thought hard, but fortunately Lee was less protective of his writing than most authors and the deletion of the passages I recommended was accepted without argument.

The last time I met Lee in Wellington he came to lunch at our vineyard in Martinborough. He had been worried when I bought the property, believing that I had sunk my retirement savings into something as shaky as horticulture. In a letter he said, “the Japanese will invent a powder that with water added will produce good wine, and then what will you do?” I replied pointing out that all my life people had been trying to invent a powder that would make a cup of instant tea and had yet to produce anything drinkable so I was relaxed about the threat to wine. Always anxious to learn something new he was happy to come to the Wairarapa and see for himself.

Mindful of the journey over the Remutakas and his dislike of the hills in Sri Lanka, I spoke to the Air Force who kindly offered to bring him in a helicopter and set him down in the football field near the house. But this time he said he wanted to come by car to enjoy the scenery. It was a mistake. A drive over these hills for the first time is not for the faint-hearted, especially those who live in flat countries, and Lee was rather shaken when he arrived. But Julie’s lunch and some of the local wines lit up the conversation and then we moved to Palliser winery with Richard Riddiford to see some actual wine-making. Though it was March, a chilly southerly had halted picking and there were no fermenting tanks to peer into. Lee was disappointed not to see the big mechanical picker in operation and contented himself with looking at the albizzia trees planted in the forecourt and irritating Richard by declaring from his knowledge of ornamental trees that they were a mistake.

After that we continued to correspond though Lee, careful as ever, was never so interesting in his letters as in his speech, and we saw him when we passed through Singapore on periodic visits to the family in London. Then a lull occurred for no greater reason than that it was enjoyable to stop over in Hong Kong or Shanghai. When I received a plaintive letter asking if I had given up travelling I understood that I had an obligation to see him. He was very old, with only a few months to live, and the visit got off to an awkward start when I found him temporarily hospitalised with a digestive obstruction from (his doctor said to me crossly) over- exercising after lunch. He seemed weak and I had difficulty hearing his opening words. Then suddenly he opened bright blue eyes and said in a firm voice, “How have you been managing these last months”, meaning since Julie died. I said, “Not very well” and he reached a hand from under the bedclothes to squeeze mine and said, “I know”.