Prime Ministers from Below – Robert Muldoon

He had a straightforward character, what you saw was what you got. He was a combative man, a squat tyrannosaurus, so what you got was not always pleasant. It was not that he was deeply aggressive. Though he sometimes looked as if he was about to punch someone, he rarely did so. His fierceness was the manifestation of a ferocious willpower. He instinctively disliked some people on sight and saw them as potential opponents. Though he always saw himself as a counter-puncher, he often liked to get his retaliation in first. He practiced, long before they thought of it, the Chinese doctrine of ‘pre-crime’, of dealing with opposition before it had actually taken shape.

He had a tough and difficult childhood which left him not with a grievance but a bleakly realistic view of the world. Underneath it all was an Irish street-fighter and when he met another Irish street-fighter like Paul Keating the sparks could fly. In March 1983, after a well-wined lunch with the National Press Club he went to meet Keating, the new Treasurer. The conversation started amicably enough but when they got on to each other’s financial outlook an angry fight broke out. Whenever the Treasury Secretary, John Stone, or I tried to calm things down they furiously told us to keep out of it. I think they were enjoying themselves.

Muldoon, small and rather shapeless, had an intimidating physical presence. Everyone from his ministerial colleagues to journalists and hecklers were a bit frightened of him, not because of the slight risk of being punched but because of that fearsome will power. Conversations could be friendly with him but never easy; everyone was always conscious of the high-voltage cable humming malevolently inside him and the risk of touching it.

As time went on his ministers, even old friends became increasingly nervous of him. At the height of the Springbok Tour troubles he chose to make a visit to Europe. After the abandonment of the Hamilton game I suggested to the Acting Prime Minister, Duncan MacIntyre, that he needed to brief the PM then in Washington. He was reluctant but I bullied him into it. He dialled the number I gave him then as soon as Muldoon answered said, “Gerald wants a word with you” and handed the phone to me.

Newer and less confident ministers often tried to lessen the risk by communicating with Muldoon through his department. It was a firm rule that we did not come between the PM and his colleagues. At the beginning a minister would come into my room and say, “The PM might like to know…” My answer would be, “Then you should tell him. I think he’s in his office now”. That largely solved the problem except with newly-appointed ministers.

There was one case where I should have applied the rule to Muldoon himself. A rather weak Minister came into his office one morning, his look making it clear that he expected to be caned by the headmaster. As I was leaving Muldoon said to me in a cold voice “I want you to stay”. He then berated the poor man to the verge of tears and I was angry at Muldoon’s cruelty in demanding that someone be there to see his humiliation. I vowed that it would never happen again and in fact he never asked me again.

Along with willpower he had an intense concentration and quickness of decision which meant that as his administration entered the 1980s he came increasingly to govern alone. It may have owed something to his accountancy training but he was a superb office manager. His office hummed with activity, a constant flow of information was absorbed and decisions taken quickly, sometimes too quickly. At his morning briefings the challenge for the briefer was to poke enough information into the crocodile’s jaws before they snapped down on a decision and made any further discussion pointless. “You think I’m wrong, don’t you”, he said on one occasion, “You may be right but if we pause to reconsider every decision we will never get on”.

The management or art of politics was his main interest and, regarding me as naive in these things, he would sometimes turn in his chair to deliver one of the maxims he had learnt.[1] I tried to get him interested on one occasion in a policy paper I had written for him. He read it cursorily and then stared out the window when I elaborated on it – a sure sign of his boredom. I filed the paper and forgot it. Months later he asked me what we had done about it. “Nothing,” I said, “you were not interested”. Sensing a slight tartness in my voice, he wheeled the chair around and said, “Mr Hensley, timing is everything in politics. That was not the time, now it is so bring the paper back and we will get on with it”. It was a good lesson: timing is as crucial in politics as it is in telling jokes.

Once he decided the timing was right the task of government was to get it done as soon as possible. When I once urged the advantage of a four-year parliamentary term, he said that he could have an idea while shaving, call an early Cabinet meeting to approve, put it into the House that afternoon and have law by nightfall – the very point that worried many people. “And while I have that power, and I should, then the term should be no longer than three years.” So he could be impatient in his use of power and impatient of the unwritten rules, the informal conventions which eased and civilised the working of the parliamentary system. He cared little for what he saw as vague and pointless behaviour like briefing the Opposition on important appointments. Conventions, though, rest on a general acceptance and once broken are hard to reset.

His mind was sharp and quick but not reflective. He had a standard primary-school education and was equipped with the old-fashioned rules of grammar which he liked to rebuke me occasionally for not observing. His deeper education he owed to the war or rather to the accountancy qualifications he gained at the end. He read current-affairs magazines and all official papers with avidity but I never saw him read a book or talk with much interest on anything not of immediate political interest.

He knew a surprising amount about gardening and was always worth consulting on what to plant in my hillside garden in Wadestown. Once in Norfolk Island he answered my half-spoken query almost absently, “It’s a coral tree”. Our house in Singapore had a terrace lined with flame trees, some of which held the beautiful moth orchid, Phalaenopsis amabilis. On Muldoon’s first visit Julie said he’s bound to ask its name and she wrote it carefully on her hand. When Muldoon stepped on to the terrace it was the first question he asked and after a quick glance at her hand she answered it authoritatively. Muldoon was impressed but Julie was less so: the verdict in her diary was, “an unlovely man”.

The carefully-tended garden at Vogel House, the new Prime Ministerial residence, might have tempted him but he left it entirely to the gardener and as far as I knew never even walked in it. When I once suggested that he needed to walk more, he said, “Mr Hensley, I take my exercise from the neck up.” He had no interest in television except for the news, although he must have watched Yes, Minister, regarded by New Zealanders as a political documentary, because he once said to me, “Don’t you Sir Humphrey me”. In music his unexpected claim that Mozart was his favourite composer was never backed by the least evidence. Politics had swept everything aside and anyone who talked to him on other subjects learnt to be careful. If he suddenly showed interest it was because he saw a point of possible political use.

That he had a sense of humour was displayed rarely – his press comment on his medical examination, “I have two of everything and all in working order” was one of the better known quips. His humour was mostly dry and understated. Early one morning in his office he asked whether I had seen a story in the morning paper. When I said that I had had no time as yet to do so, he turned to me looking over his glasses and said, “You should read The Dominion, Mr Hensley, it doesn’t take long.”

Occasionally, on a long flight or car journey, he would reminisce. He neither swore nor ventured into any improper topic. The nearest he came was a story about a member of Parliament for (I think) Kapiti. He said that if you represented a dairy-farming electorate there was some competition in Parliament to get a speaking slot around five when many voters would be in their milking-sheds with the radio on. This member, as was customary in that time slot, was dwelling on the merits of his electorate. ‘Mr Speaker, sometimes when I am driving home in the early hours of the morning I see a light on in a lonely farmhouse and I think, “there’s a man who is up and doing himself a bit of good.” The whole House dissolved in laughter and in telling it so did the Prime Minister.

His occasional jokes in the office were more dry. I decided to give a background (not for attribution) briefing to a reporter on why the Government was sending a scientific group to the French testing site of Mururoa. To my horror it appeared as the lead story in the Evening Post attributed to a senior Government official. I went at once to see the PM and my horror was increased by seeing him standing at his desk contemplating the story. I said, “It was me, Prime Minister”. “No it wasn’t,” he said without thinking, saying he had rung the Minister of Foreign Affairs to complain. When I finally convinced him, there was an uncomfortable silence, very uncomfortable at least for me. Then he looked up with a hint of a grin and said, “Bet you won’t do it again”.

He also liked an occasional tease. When he told me to call Cabinet to authorise a wage freeze, I got hold of Bernard Galvin, the Treasury Secretary, and we hastily drafted a paper on its undesirability. When I took it to him, he snapped, “I know what you are saying and I don’t agree”. I said that at least he could do us the honour of reading it. He snatched the paper from me cast his eyes over it and then handed it back saying, “There, I’ve read it”. Three months later he said to me, “Do you know what day it is, Mr Hensley”. I realised I was being teased but racked my brains without result. It was a hundred days from the imposition of the freeze and we had said in our paper that no freeze had ever held longer than a hundred days. So he had read it more carefully than I had thought and enjoyed pointing out that despite our claim the freeze was still watertight.

Even religion for Muldoon was political. I took him once to meet a KGB defector, Stanislaus Levchenko. When I told him that Levchenko had defected because of a religious conversion, Muldoon was or professed to be horrified that anyone could be so careless of politics. He liked the Catholic bishops to a certain extent and the Salvation Army rather more; the rest he felt had abandoned the Gospel for social welfare. He was critical of an eminent judge, Sir Alfred North, for a commission he had chaired, and said to me that it was because North was a Baptist. When I protested (North was known to both Julie’s and my families and my mother-in-law even had a dog called Alfie), Muldoon turned to me and said, “Mr Hensley, you’re a Catholic and don’t understand. I was brought up as a Baptist and I know what I talking about”. I was squashed and never knew what Sir Alfred had done wrong.

His marriage was a conventional arrangement but not a union of minds. Their personalities were such that when you were in the company of one you tended to feel sorry for the other. He was widely rumoured to be unfaithful and this was plausible because he was one of those men who regarded women as either untouchable ladies or fair game. Tam, as he always called her affectionately, was however The Wife and always to be treated with the respect he gave her. Her conversation, at least in my experience, seemed to be limited to household matters and packing but it was always good-natured. Occasionally when we were travelling and having a discussion she would offer a thought. Muldoon would stop and say, “Yes, Tam” and then after a respectful pause we would resume the argument.

Her life revolved round ‘Bob’ and looking after his daily needs but she showed some strength of character in doing so. Coming back from the New Delhi Commonwealth meeting, she learnt when we landed in Auckland that her deeply-loved father had just died. Bob however wanted her in Wellington so she concealed her grief and went on. She must have had an inner toughness; when her husband died few other widows would have relaxed by making a lengthy trip up the Amazon.

In a few respects he was more conventional than his predecessors. He was the first Prime Minister to entertain overseas guests and others at regular dinners. Vogel House was well-adapted for this. He liked good food and wine and recruited Air Force chefs to provide it. The atmosphere round the table varied. Some of the dinners were grisly affairs, like the one for the EU Commissioner whose deal on sheepmeat tariffs had just broken down because of Muldoon’s negotiating intransigence. At others Muldoon, not easily given to small talk, could be a sparkling host. At a lunch for Prince Charles, Princess Diana sulked and pushed her food around the plate with her fork, making clear the difficulties of her marriage, but Charles and Muldoon managed to keep the conversation going for the whole table.

However the dinner went, my unspoken task was at 9.45 to make ‘My goodness, is that the time’ noises and encourage everyone to leave so that the PM could watch the ten o’clock news. As soon as we were outside he would shove the bolt home on the front door and race upstairs for the TV. On one unhappy occasion, the dinner ended at 9.30 and the guests milled about in the dark courtyard waiting for their cars to arrive.

He was equally methodical about travel. There were little rituals to follow. Soon after takeoff he would discard his suit jacket and pull on an ancient rugby club jersey before ordering a drink and settling down with a magazine. He then had dinner and some wine which we both liked to talk about. On one journey I had my first taste of a New Zealand Syrah, a 1976 from Martinborough, and it was so good I persuaded Muldoon to try it. Then he ordered the rest of the only bottle on the plane and we drank it.

On this occasion no doubt but on most flights he slept well. When he didn’t he liked to talk; long flights and long car journeys were almost the only times it was possible to have a talk with him that was not on business. Talking this way in the darkened aircraft on a flight from Tokyo he told me that the thing he most regretted in his life was his ‘outing’ of Colin Moyle one rowdy Thursday evening in the House. This confession cannot have been for show, since he knew I would never repeat it, and remains a unique case of Muldoonian remorse.

In the office he was brisk and decisive. A paper sent to him would often come back in twenty minutes, read and decided. He enjoyed the pressure of government business. On rare but memorable afternoons he would run out of things to do and appear in the door of my office, looking around vaguely as if he had never seen it before. On the advice of my predecessor I tried to set aside some papers to keep him occupied on these occasions until something more demanding turned up.

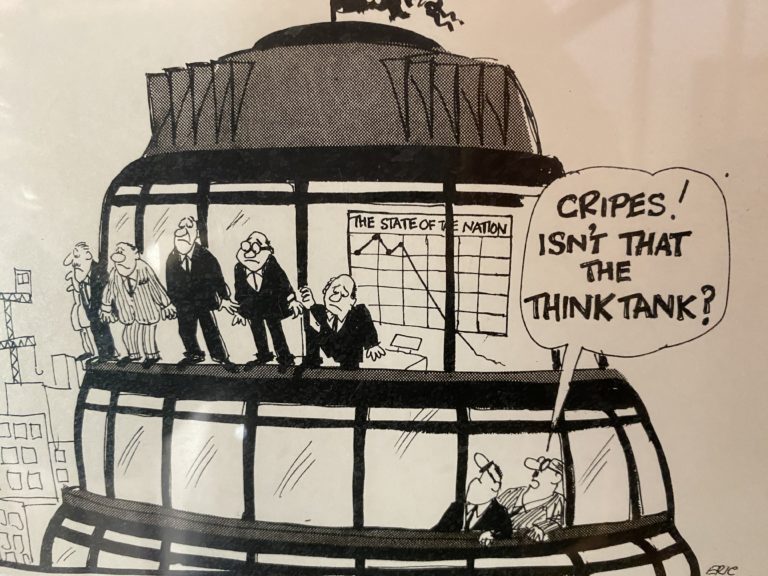

The key to his dominance as Prime Minister was his control and use of information. As soon as he took office at the end of 1975 he re-established the Prime Minister’s Department as a separate entity and created something new to the New Zealand government, the Prime Minister’s Advisory Group. It was a small number, never more than seven in my time, of bright young men and women who each had a ‘portfolio’ or area of responsibility. Their task was to keep in daily touch with their ministries, businesses, unions and other interested parties to ensure that the PM knew of any problems that were developing. It contributed to his mystique and strengthened his influence over his colleagues because he sometimes raised an issue before the responsible minister knew of it.

The Advisory Group was an administrative body not a party one, designed to give the Prime Minister better control over his sprawling government and not to polish its appearance to the public. He did not look to his advisers for political or emotional support and cared nothing whether they voted for him or even liked him. All that mattered was whether they were good at supplying the information he wanted. When Bernard Galvin was approached to be the first chair of the Group he felt obliged to tell Muldoon that he had voted for his opponent in the election just finished. Muldoon ignored this, he wanted Bernard for his ability not his politics. After the last Group meeting before the 1981 election he remarked placidly to me that if the election depended on the votes of the Group he did not think he would get a majority.

Working for Muldoon was never easy or comfortable but his advisers enjoyed a privileged relationship in which he was never angry or other than forbearing. They enjoyed the sort of immunity granted to those birds who are permitted to pick the teeth of a crocodile basking on the sandbanks of the Nile. Proposals I made that he did not like were promptly rejected without any suggestion of resentment. At a Cabinet committee meeting he looked at a note I had given him and said with some surprise, “For once I agree with my own Department”.

Whatever their private opinions members of the Group were always required to have a background of political neutrality.[2] I happened to mention to the PM that I had hopes of recruiting a woman who seemed especially suitable. He looked up and said to me, “I have heard nothing but good of her”. I sensed a tease and when I looked further into her credentials I found a National Party connection that disqualified her. He never enquired further, that would have been interfering in my responsibility.

On another occasion I had appointed Tim Groser to the Foreign Affairs ‘portfolio’ when a rather bitchy piece appeared in The Listener saying how much his old comrades on the Committee for Vietnam would miss him and with a photograph of a heavily-bearded young Tim looking to be peering through a lavatory brush. I had known Tim since he had first worked at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs but all this was new to me and the Prime Minister was naturally uneasy. I said I would look into it. I did and when I said I had full confidence in Tim the PM nodded and forgot it – it was my responsibility not his. Tim went on to become Muldoon’s resident adviser when he started his campaign for a New World Order.

The Group reported only to Muldoon and two hours of every Friday afternoon were set aside for each to sit around his armchair and report in turn. The time was sacrosanct and everything else had to be reshuffled around it. I think he came to regard those two hours as his relaxation at the end of the week. Though always a formidable man, at those meetings he was more a benign grandfather, listening carefully to his young team, chuckling occasionally at their comments and never, except by gentle implication, being critical.

It was my job to select, recruit and supervise the work of the group. Though the Labour Opposition could not believe it, the members were chosen by me not the Prime Minister. They were bright people in their mid-thirties, chosen from the comers in private companies and the best from government departments and they served for about two years – not long enough to put down roots and start to become a bureaucracy. The aim in keeping it small and regularly refreshed was to keep it quick to react and to prevent it becoming another layer of bureaucracy and supervision like the White House staff.

As a result I spent considerable time recruiting, an onerous business because with such a small group every individual was important and one mistaken choice would have been a disaster. The short term, though, was an advantage when I had to persuade someone running a big company to give me one of their most promising juniors. There was no risk of my poaching them for a longer term and most could see the advantage of a future senior executive having experience of the inner workings of government. I tried in recruiting to keep a rough balance of half from the public sector and half from the private, so that the first learnt something of the business outlook and the second, often to their surprise, discovered the disorderly range of events democratic governments had to deal with.

The importance of the group accidentally increased after the ‘colonels’ coup’ when a group of his Cabinet colleagues attempted to overthrow him while he was overseas in 1980. The PM’s press officer, Gerry Symonds, told me the plotters had achieved a majority but Brian Talboy’s refusal to replace Muldoon left the coup leaderless. With that assistance Muldoon recovered his position with a display of extraordinary willpower. He spent a day’s stopover in Honolulu on the phone. Then back in the country, even as Gerry was telling me he was adrift, he was hauling himself hand over hand back into the boat. After two days he was safely inside and throwing the others out. At the end of the process he was exhausted, so tired that he fell asleep at the Friday Group meeting, the only occasion this ever happened.

Thereafter he seems to have lost confidence in his Cabinet colleagues and increasingly governed on his own. To do so he needed timely information and so relied more on his officials, not only the Group but the officials in other departments that he knew and trusted. He once said to me that the reason it was much better to be in Government than in Opposition was access to officials. He increasingly referred in public to the views of “senior and experienced officials” (those who agreed with him) as opposed to a scorned class of “junior and inexperienced officials” (who did not ). But the days of a quick call to the heads of the producer boards or the CTU were over. He continued to get good information and advice from his officials but the effect was less and less perceptible as he fought his increasingly lonely battle to keep New Zealand the way it was when he returned from the war.

As is often the case with Prime Ministers he developed a growing interest in foreign policy which required no tedious preparations and gave refreshingly quick publicity. He had no deep or strategic views on this but his constant reading of current-affairs magazines kept him up-to-date with the detail. If he had a strategic principle it was that you should stick with your friends, unless like Australia’s Malcolm Fraser you disliked them. In fact his foreign policy came down to a rather schoolyard distinction between those he liked (Margaret Thatcher, Lee Kuan Yew, Ratu Mara, Emeka Anyaoku) and those he did not (Walter Lini, Indira Gandhi and Jimmy Carter). At a press conference he referred to President Carter as “a peanut farmer” which caused some irritation in Washington. Lee Kuan Yew was fascinated by such outspokenness – he thought everyone in South East Asia agreed with Muldoon’s verdict but no-one would have dreamt of saying so out loud.[3] Months later Muldoon complained to me, “But I was right about Carter, wasn’t I?”

On his growing number of overseas visits his views, expressed clearly and intelligently, were listened to with respect not only by Lee but also by George Shultz and other members of the Reagan Administration and, with occasional murmurs of dissent about his economics, by Mrs Thatcher. His position on the Springbok rugby tour, though, blackened his name in the Commonwealth and for much of the developing world. It led even to the Commonwealth Finance Ministers meeting, which he would have chaired, being shifted away from Auckland to the Caribbean.

Then this rift, which seemed lasting, was healed in an unexpected way. He became increasingly concerned about an unbalance in the world economy after the dramatic rise in the price of oil. The penalty fell heavily on developing countries, and he began a crusade for a New World Order to redress it. Despite the views of many, including his own advisers, that the international economy would rebalance itself without drastic change, he made energetic and persuasive speeches on his travels and wrote (or rather Tim Groser did) an article in Foreign Affairs which attracted some notice.

As a result at the next Commonwealth meeting in New Delhi in 1983 he found himself unexpectedly popular and Julius Nyerere of Tanzania told me enthusiastically that he now wished the Finance Ministers’ gathering had stayed in Auckland. I was commissioned by the meeting to draft a statement for the assembled heads of government of what was essentially Muldoon’s views. Commonwealth drafting committees are notoriously indifferent to time but by withholding lunch until we finished I managed to produce a text by mid – afternoon. As I sat behind the Prime Minister listening to Mrs Gandhi endorsing it, I felt a tap on my shoulder and turned round to see Lee Kuan Yew who whispered, “It’s very good but it won’t make any difference, you know”. He was right about the world’s economy but it did make some difference; whether or not Muldoon intended it the campaign repaired some of the damage which the tour had done to our reputation.

The New Delhi meeting was the first where I was able to add a doctor to the delegation, since we were travelling in an RNZAF aircraft. It was also the first where I thought the press group should pay for their travel. This turned out to be a double-edged sword when Muldoon suggested that Margaret Clark and Julie should also come with us and their fares had also to be paid for. Julie and I had no sooner reached our hotel room than the phone rang and a voice informed me that Mr Roly Ford was coming. I thanked him politely for this mysterious news and began to unpack. The phone rang again with the same message repeated more urgently It seemed to belong to the many unfathomable mysteries of India and I ignored it again until a third call revealed the caller to be in a state of almost hysterical excitement: “Mr Hensley, MR ROLY FORD IS HERE.”

I went down to the guard-room at the front of the hotel and found my daughter Caroline and Richard Riddiford in the custody of three soldiers.[4] The guard was perhaps larger than necessary because the blonde Caroline was fetchingly dressed in a shalwar kameez of apricot-coloured silk. They had been in Varanasi making a documentary for TVNZ called Benares, City of Light. This made the Commonwealth meeting something of a family occasion for us, though Julie probably had the best of it. With the Taj Mahal closed for their pleasure, she, Hazel Hawke and Thea Muldoon spent a morning walking through the deserted monument, all three, Julie claimed, meditating on what real husbandly devotion could do.

The doctor, mercifully, was not much needed. His only patients were two or three members of the press corps and himself, all caught by drinking the bottled water obligingly provided by the hotel but refilled from the nearest tap by the eager man who waited outside the door. The hot weather was only starting to build but it became uncomfortably hot in the aircraft as we waited for clearance to leave. We sat patiently with door still open, informed that there was a queue ahead of us and it would take some time. I was a little slow the grasp the meaning of this but said to the PM’s Private Secretary, “Ask them how much?” The answer came back swiftly, $US300, but when I told Harold to pay it he asked ‘under what item’. From Muldoon, lying sweating in his chair with a magazine over his face came a rumble, “Put it down to disbursements”. When that was done the doors closed and we were away and months later I noticed a sum of $371.70 in the Treasury accounts labelled ‘unsupported gratuity’.

The following year, a few months before the election, he went to an OECD meeting in Paris, where his unorthodox economics were more fashionable and then on to London for a follow-up Commonwealth meeting on his proposals and a call on Margaret Thatcher. The talk was as comfortable as ever as we sat in her chintz-bright sitting-room at No. 10, even though she told him that market forces and the IMF would correct the imbalances in the world economy that were troubling him.

After that we travelled by Concorde to New York where the President’s aircraft (but only Air Force Two) took us to Washington. There for a morning he held court in his hotel suite as senior members of the Reagan Administration called on him. The first was Donald Regan, the Treasury Secretary, who was urged to overlook New Zealand’s disregard of the GATT Subsidy Code. When Regan protested that he could hardly make an exception for New Zealand, Muldoon said, “Go on, Don, you can do it” and he did.

Then George Shultz, the Secretary of State, arrived. They were old friends and after an amiable talk he left to brief the President. After a decent interval we left for the White House Cabinet Room where the President sat flanked by Shultz and Caspar Weinberg the Defence Secretary. We began inevitably with the Subsidy Code. The President shuffled the index cards in front of him disconsolately, lapsed into silences and began to remind me of his own joke about being woken up in a crisis “even if I am in a Cabinet meeting”. Then the six of us adjourned for lunch in the Family Dining Room upstairs where a different Reagan appeared. Relieved of the Subsidy Code he sparkled with conversation, told jokes and was the life of the gathering. Then he and Muldoon went down to give an afternoon press conference in the Rose Garden and we left, having taken up much of the Reagan Administration’s day. No-one was to know but it was the last outing of the old ANZUS relationship before the nuclear ships quarrel later in the year.

After that we wandered around the United States rather aimlessly. After nine years he was tired, domestic politics was a burden and travel a relief. We went to New Orleans for the Carnival, visited the white tiger (my contribution), then drove around a ranch in Texas owned by a brisk woman with a long tweed skirt and a husband who was frightened of her, called on Lady Bird Johnson and her daughters, attended a seminar at Berkeley University in San Francisco and came home to a political scene more untidy than ever.

In May the Labour Opposition introduced a bill banning nuclear ship visits. In a rancorous debate two National members defected to the other side and the bill would have been carried but for two Labour members going the other way. The writing was on the wall and Muldoon, always a fatalist, asked me to check how soon he could call an election.

The outcome was never in doubt even for Muldoon whose campaign, tired and dispirited, was a shadow of his past battles. Then his predictable loss was turned into a constitutional crisis by his stubborn and irrational refusal to recognise that without a significant devaluation of the over-valued currency our reserves would vanish the moment the foreign exchange markets were opened. He had an emotional view of devaluation as a wrestling-match between him and greedy speculators rather than as help for an overweight jockey riding a tiring horse. His defiance could not be sustained and his Deputy, Jim McLay, persuaded him to let it go.[5]

So an intelligent and strong-willed politician left office under a cloud. He stayed on in Parliament and in a select committee on my estimates used his inside knowledge of the PM’s Department to such an awkward extent that I got flustered and inadvertently called him ‘Prime Minister’. He continued to make frequent statements, among them the surprising one that he had always assumed I had voted Labour. I rang him at home to complain and the phone was snatched up at the second ring, a sad glimpse of an aging leader sitting by a phone which no longer rang much. I made an angry protest at this breach of my political anonymity. He said plaintively, “I was only trying to help”. It was the sternest complaint I had ever made to him and perhaps I should have evened the score by saying ‘Bet you won’t do it again’ but I was too cross.

We did not speak again for a year or so. He was still Leader of the Opposition and I was preoccupied working for a new Prime Minister and trying to hold my own position. One evening at Government House he was circling round our group and Julie said to me, “He’s dying to speak. Go and make it up with him.” I did and after I returned home from a year at Harvard, Julie again urged me to make a visit, saying he did not have long to live. I went to his office at the back of Parliament Buildings and he talked at length about his forthcoming biography, opening and shutting drawers to show the files he had made available. Nearly two hours went by in a relaxed and reminiscent way until I had to leave him for another appointment. As I went I reflected that this was perhaps the first time in our association that he had wanted to prolong a discussion.

He died not long after and his funeral was a rather bizarre occasion in the Auckland Town Hall. I found myself walking in with David Lange who whispered, “Is he really dead? I have got some rosemary in my pocket just in case”. The theatre was full and the atmosphere lively rather than grieving. Halfway through a hymn the organ wabbled uncertainly to a halt and the theatre went dark. There was complete silence, broken by David Lange’s voice out of the darkness, “That settles it. Rod Deane will have to go”.[6] After a nervous wait the power and the organ recovered and the speeches went on until there was tremendous crash. It turned out to be a full-throated haka by the Mongrel Mob delivered from the dress circle. The ceremony had little of the ‘tidiness’ Muldoon liked for a formal event but perhaps it was a true reflection of his unquiet spirit.

[1] See my paper The Management Maxims of Sir R. Muldoon.

[2] This was a Galvin requirement that I carefully observed.

[3] Lee’s own comment to me.

[4] Richard Riddiford was the son of a Wellington lawyer and not his Martinborough cousin.

[5] See my article, The Devaluation Crisis of 1984.

[6] Roderick Deane was chairman of the New Zealand Electricity Corporation.