Daydream Diplomacy

When you think about it, our obsession with independence as the main feature of our foreign policy is odd. In speeches by politicians and academics the term foreign policy rarely appears without the word ‘independent’ in front of it. All nation states have an independent foreign policy but only we seem to feel the need to buttonhole everyone we meet to point this out. We have been independent for over a century. Geography means that few if any countries face less of a threat to their independence than New Zealand. That we continue to assert it with some vehemence suggests that something is wrong, that we have lost confidence in ourselves.

Take, as an example, the NATO gathering to which Jacinda Ardern was invited when still Prime Minister. Her message to them, at least as reported, was that we are not just independent, but “fiercely independent”. Perhaps the gathering suppressed a smile at the thought of one of the freest countries in the world being so anxious about this, but our independent thinking has developed an important corollary, that we are not just independent but unattached as well.

The message that Ms Ardern’s NATO audience might have taken home is that it may suit us for a time to work with NATO but if circumstances change we are independent and will go our own way. To tell a group of friends that we cannot be counted to stick with them is a peculiar way to win their support, but that is what our leaders have been saying for a generation when they emphasise our independence.

As a recent newspaper article puts it, “taking an independent stance doesn’t mean we won’t work with other countries, just that we will decide when it is and isn’t in our interests to do so.” This appeals to our nationalism but we do not seem to have thought about how it would work in practice. Diplomacy is not a pick ‘n’ mix opportunity, it works by a network of mutual obligations. Any country in which we are interested will want to know what they might get in return, what we are doing to advance their interests. International friendships are not chess pieces on a board, they are organic, growing gradually as common interests build trust.

The growth of trust takes time. For this reason alone, the idea of New Zealand as the playboy of the western world, open to offers and able to choose its partners free from the demands of our traditional friends is a delusion. At the risk of stating the obvious, partnership is not our decision alone. Another partner must decide whether we are worth it to them and for what purposes.

A few years ago we dipped a cautious toe in this new freedom when China tore up the international treaty it had signed to guarantee Hong Kong’s liberties. Our four closest friends denounced this lawless act but we decided not to join them. Indeed, our Foreign Minister complained, not of China’s action but of being pressured by our friends.

The moment passed and I think we were shamed by the ease with which fear of China made us discard deeply-held principles. No-one said so but it was clear that experimenting with an innovative and independent foreign policy was not possible. Whether we like it or not, we are prisoners of our history and geography which will always limit our choice of diplomatic friends.

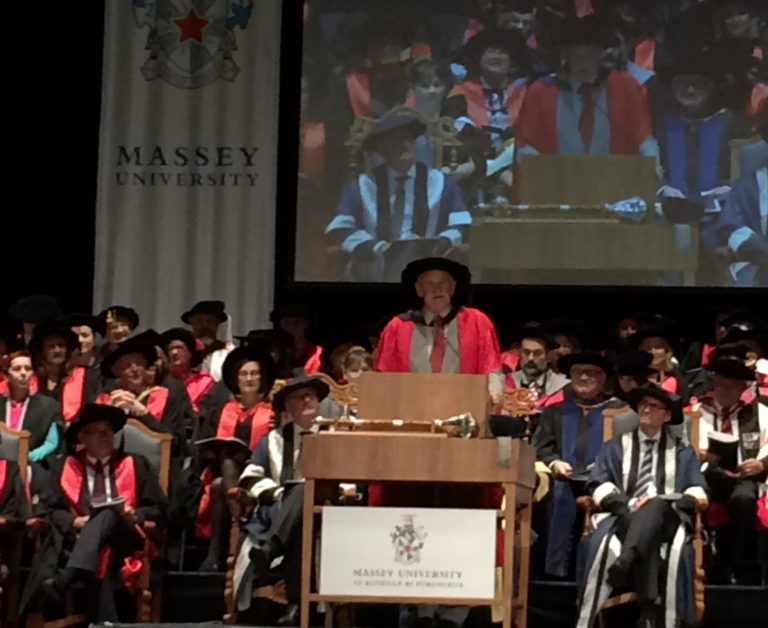

Daydream diplomacy, however still holds us. A meeting of defence ministers in Singapore was recently addressed by our representative, Andrew Little. Although he is an intelligent and widely-respected minister, he found himself asserting that New Zealand’s anti-nuclear stance is “not wishful thinking”. It must have struck others in the room as almost the definition of wishful thinking. For forty years New Zealand, with no threat, no nuclear arms and therefore nothing to give up, has marched along bravely behind the banner of nuclear disarmament and throughout those years not a single country has joined us. To press on with a policy that has failed to achieve anything in nearly fifty years might be seen as deeply eccentric.

Nuclear disarmament, however, is felt like independence to be an important part of our self-image, a banner too sacred to be doubted by results. It is another sign of the way in which our foreign policy has become, not a way of communicating with the outside world, but of talking comfortably among ourselves. Whatever Mr Little or other politicians may think privately, they know that the voters they represent have come to think of the policy as part of themselves and there is little to be gained by suggesting a review.

As we sit congratulating ourselves on being independent and nuclear-free in the world of make-believe, the real world is passing us by. This mattered less in the long peace where there were no threats to us and nothing to puncture diplomatic daydreams. The long peace has begun to wobble, with a major war in Ukraine and an equally major one threatened in Taiwan. Now the Asia-Pacific region has begun what looks like the first serious effort to organize a collective defence. In Singapore every representative except New Zealand was working energetically to create a network of defence understandings and agreements, not led by the United States but designed to wrap the US in a lattice of regional commitments. What is emerging is a platform of collective security in the face of the region’s widespread fear of China. As this takes shape New Zealand will have to do more than say that its anti-nuclear stance is not wishful thinking.

We need to recognize that we have got on to the wrong track. The obsession with independence and nuclear disarmament is the sound of people in the dark, whistling to keep up their spirits. Our withdrawal into isolation, our discomfort with our old friends, our retreat from solid thought to fantasies of how, freed from our traditional barriers, we will be able to make new friends, and even the strange claim, which contradicts all evidence, that New Zealand is not part of the West, all seem to be signs of how far we have drifted from our historical roots and our increasing discomfort with the journey.

The remedy is in our own hands but it will not be easy to reverse an ingrained complacency. Public opinion, apathetic at present, will have to wake up to how far we have drifted from our friends. We need to recover the old boundaries of a realistic foreign policy, repair the mildewed relationship with Australia, pay much more attention to the ASEAN countries and stop regarding the South China sea and Taiwan as faraway problems of which we need to know nothing. If we can do this we will recover our confidence and will be so obviously independent that it will no longer be necessary to mention it.