A Year at Harvard

In August 1989 David Lange resigned and I found myself out of a job. He had created the position of Coordinator of External and Internal Security to cover the abolition of my former job as head of the Prime Minister’s Department but now even that was likely to disappear with a new Prime Minister. I became a political exile in my own country and a nuisance.

In the course of some urgent thinking I remembered the offer made to me by Harvard several years earlier of a fellowship at its Centre for International Affairs. I was then head of the Prime Minister’s Department and had to decline the offer since I could hardly tell Sir Robert Muldoon that I planned to be away for a year. I wrote to Harvard to ask if the offer might still be open. They replied warmly, saying that the academic year had already begun and the sooner I could arrive the better.

A few days later I was in Cambridge (Massachusetts) getting started. I was given a large and comfortably furnished flat across the road from the Law School and the entrance to the Yard and an office in the Centre for International Affairs, which from an obvious sensitivity always abbreviated its initials to CFIA. An apology was made for the university’s inability to provide me with a secretary. Instead I was given an IBM laptop, which I had never seen before, and rudimentary instructions on how to use it. The Dominion newspaper in Wellington had commissioned a series of articles from me about life at Harvard. Using the laptop turned out to be like learning to ride a bike. I wrestled with it for hours in the evenings, saw all my copy fall off the screen and then discovered how to retrieve it, until finally I wobbled away confidently and had no more trouble. It may be the most useful thing I learnt at Harvard.

The fellows at the Centre were geographically varied though most were American including a lady admiral. Besides me, there were two other political exiles. One was a former president of Lebanon who had spent many months underground being shelled and seemed to enjoy simply walking around. The other was a quiet Israeli major-general. I came into the common room for a coffee and saw him standing at the window looking down at one of the student demonstrations so common at Harvard. When I speculated about the subject he said modestly, “I’m afraid its me.” He went on to head the Israeli Labour Party but sank in those stormy politics.

Everyone but the Lebanese and I seemed to be researching or writing a book. I was numb from years in the Beehive and concentrated on the marvellous opportunities the university gave for recharging intellectual batteries run down by years of use. Fellows were honorary members of the faculty, could sit in on any lecture they wished, could eat at the Faculty Club and, best of all, had access to the stack at the Widener Library. The Library had been given to the university as a memorial to a young man drowned on the Titanic and was munificently funded. Behind the public area – the issuing desk and study tables – was an enormous stack of books, one of the largest in the world. You could pace along steel gratings, searching the shelves and looking down on three or four floors of shelves below, all filled with books. An hour or two could go by in this pleasant search until you emerged with an armful of volumes to take home.

I sampled a number of interesting lectures but the course I never missed was Harvard’s great series on the history and literature of China, known to generations of student as the ‘rice paddies’ lectures. It was before Xi Jinping and China’s drift into totalitarianism and was history at its best, sympathetic but detailed and accurate. I took pages of notes at each lecture and recovered a youthful excitement in learning.

I sat next to John K. Fairbank, the architect of this course, at one of the dinners to which hospitable faculty members would invite me. We talked about T’ang poetry, about which I knew little, and he arranged for a young lecturer to translate some of Tu Fu’s poems for me. The translation was only of the English meaning of each individual character, leaving me to put the often telegraphic brevity of the original into English verse. It was much better than crossword puzzles and whatever the quality of the result it gave me a closer knowledge of some of the best Chinese poetry.

My Japanese studies were marked by a dramatic debate. Great universities are supposed to foster free and knowledgeable discussions and this was a rare example of it actually happening. Word went round of an afternoon’s debate between Karel van Wolferen, a Dutch journalist and Japanese expert whom I had never heard of, and Harvard’s own formidable Japanese faculty. When I got there the lecture theatre was packed to the rafters and my seat was so high that I sat with a rafter beside my ear.

Wolferen spoke at length and his view was gloomy. He argued that the Japanese property boom would soon collapse, that exports could no longer carry the economy, that it would collapse into deflation and predictions that it would overtake the US economy should be forgotten. This detailed indictment was challenged with varying degrees of caution, especially by Ezra Vogel who had written a book called ‘Japan will be Number One’, but most of us walked away feeling distinctly uneasy. Wolferen proved to be right on almost every point and Japan fell into a deflationary trap which deprived it of decades of growth. The point is still important. China now faces the same challenge, to move from an over-reliance on property and exports to a better-balanced economy. If it fails it faces the same deflationary trap and its hopes of overtaking the US will be in doubt.

In general, though, my studies on Japan and other subjects like zoology were carried on simply by sitting in the offices of the relevant professors. I had learnt from my time with the CIA in Washington that knowledgeable people enjoy being asked to talk about their specialty. Professors who seemed to have more time on their hands than their staff appeared to be happy to share it with someone of their own age. I regularly called on the professor of Japanese -she gave me lists of books and help with my winter clothing – and on Stephen Jay Gould to learn the mysteries of ‘punctuated equilibrium’, the modification he had proposed to Darwin’s theory of evolution, after being fascinated to learn that traces of iridium found in New Zealand were the first evidence of the asteroid collision 66 million years ago.

My other, most consistent study turned out to be J S Bach. The professor was the great Christoph Wolff, a member of the Bach Society in Leipzig, and his vigorous pronunciation of ‘Bach’, bouncing off the walls at the back of the room, was itself worth a visit. I was introduced to him by watching his ‘party trick’ for first-year students. He was making the point that in his unaccompanied violin sonatas Bach was aiming to make us sense the missing accompaniment. On the stage he arranged for the violin part to be carried by a speaker while he improvised a quiet accompaniment on the piano. “You all heard that right to the end,” he said, and then paused, “except that I stopped playing halfway through. You went on hearing the missing accompaniment because Bach intended you to.”

A teacher as good as this was not to be lost and so I called regularly at the Music Department where he like others seemed happy to share his time. He worked with recorded examples to improve my regrettable ignorance of much of Bach’s organ music, went through most of the keyboard fugues that I had been playing for years, pointing out what I had missed, and kept me informed of Bach concerts at the university or in Boston.

On late Sunday afternoons in winter I walked through the snow to the Busch-Reisinger building to hear recitals on its soft, breathy chamber organ, so much better suited for the intricacies of Bach than the steam-driven, Victorian organs. I remember in particular a performance of his Gigue fugue but not for the music. The organist was rather small and playing the fugue at speed took all his effort. His legs shot in and out at angles to press the pedals, his arms raced back and forth on the manuals as he pulled stops out and in and his little bottom bounced up and down on the bench with the effort. As he said, he was the one doing the jig and the sight was so compelling that I failed to listen much to the fugue.

Attendance at lectures and all other occasions was simple since all were within comfortable walking distance from my flat. I had no car and unlike the sprawling campus of a university like Stanford, Harvard was compact, made for foot traffic. Even walking there was interesting. To cross the busy Massachusetts Avenue to get to the Yard required a pause on a traffic island to wait for the lights. It was called William Dawes island, the only traffic island I have known to have a name. Dawes had been a minuteman who, like Paul Revere, had galloped to Boston to warn of the approaching British. His descendants, perhaps peeved at his receiving only the meagre recognition of a traffic island, had installed a series of brass hooves to show where he had galloped along the edge of Cambridge Common but he remained obstinately obscure.

Even so Dawes Island had its rewards. When walking to the Yard it was sometimes necessary to wait on it for the lights to change. I would occasionally meet the great economist, Kenneth Galbraith, here and we talked as we waited. On one of these occasions he told me a favourite story about his first job working in Washington in 1942. To save rubber the President had decreed a speed limit of 35 mph. Governor Stevenson of Texas would not comply and the new Ph.D was deputed to persuade him. He explained the need in a long telephone call and then was silenced by the Governor who said, “Dr Galbraith, here in the great state of Texas if you drive at 35 mph you don’t get there.”

Apart from Dawes, all the memorials round my flat seemed to be of George Washington. He had taken command of the Continental Army under an elm tree in the Common and had installed his headquarters in a handsome brick building at the entrance to the Yard. In the Mess there every night he was said to finish dinner by proposing the loyal toast. At Christmas, 1775, he and Martha went to the service at Christ Church in the middle of the Common. Three months later, when the British withdrew from Boston, the entire congregation also withdrew, moving to Nova Scotia and Ontario, leaving the little church abandoned for fifty years. We attended on Sundays when Julie was with me. Reading the preface to the American edition of the Book of Common Prayer was always worthwhile, as it grappled at considerable length with the delicate issue of why a church founded with the King as its Supreme Governor now had to exist without it.

There was a very large movement of loyalists to Canada – the Canadian Consul-General in Boston told me the movement of people was even larger than the flight from Castro’s Cuba. It was these arrivals, the United Empire Loyalists, who together with the French in Quebec gave Canada its most abiding characteristic: not-being-American. Loyalty to the throne was still cherished. At dinner one night in Kingston, Ontario, I became so engrossed in my coffee that I failed to notice everyone getting to their feet when God Save the Queen was played on the radio. “We thought you were so loyal in New Zealand,” my hostess said reproachfully.

Walking on the Common occasionally gave an echo of another great event in American history. In late autumn I came upon a little ceremony commemorating the reburial of ten soldiers of the 58th Massachusetts Regiment brought back from South Carolina. I had missed the speeches but a black Shriners’ band played and then several grey-haired ladies stood together and sang ‘Amazing Grace’, their quavering voices carried away by the wind.

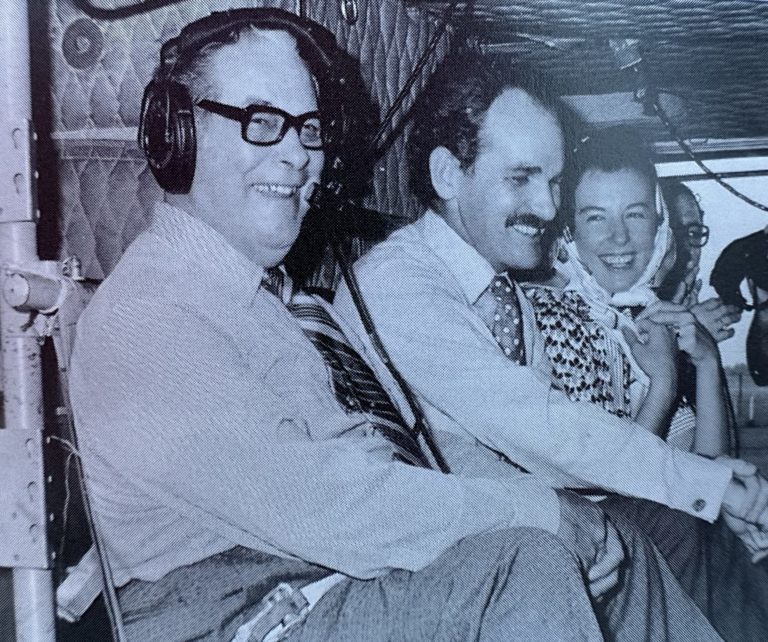

The excitements of Harvard never flagged but it was generous of Roderick Deane and the Electricity Corporation, where Julie was Director of Corporate Relations, to find excuses to enable her to join her husband on two or three occasions. The first was a visit to northern Italy to see where a hydroelectric dam had collapsed. It was just before Christmas and the opportunity was not to be missed. As soon as she had finished her report I flew to Milan and joined her at the Hotel Europa in Venice.

It was mid-winter but the city was bathed in lemony sunshine which made walking a pleasure. On Christmas Eve there were few tourists, the streets seemed to be full of little girls in capes running to the shops for cakes and pastries. We went to midnight Mass at St Mark’s, past the porphyry statue of a late Roman emperor and into the Byzantine gold of the interior. A stern-faced verger was expelling a group of Japanese tourists but accepted us. The music would have pleased Vivaldi and we did our best to follow the sermon preached by the Patriarch of Venice, the office itself a creation of the Byzantine empire. On Christmas Day we dined in the hotel restaurant at a little table by a window looking across the Grand Canal to San Giorgio, discovering a superb Italian red called Brunello di Montalcino of which we drank so much of it that we slept through the rest of the day and until breakfast.

It was another honeymoon. We had devolved the care of my aged parents on our children and, neatly free of our responsibilities to both old and young, walked through the fondamenta of Venice or took the vaporetto to the more remote churches and galleries. After a week, still off the leash, we took the train to Florence for another week, staying in a pleasant room I had booked from Boston.

The room, an arched medieval chamber large and well-lit, turned out to be where St Philip Neri had been born. He was unknown to my Anglican wife but not to Winston Churchill who adapted his most famous saying to remark, as Sir Stafford Cripps walked by, “There but for the grace of God goes God.”

We walked the streets and dined every night at a nearby trattoria. It featured a padrone who sported a blue blazer, suede desert boots, was the image of Julie’s Uncle Ted and looked after us zealously. On New Year’s Day we walked in bright sunshine up the road above Florence, looking down on the dome of the Duomo, past an ancient church dedicated to St Leonard (it would have horrified my Presbyterian grandmother to find she had called her son after an Italian saint) and up to the house where Tchaikovsky loved to stay.

We invited Julie’s cousin, George Bortolini-Young, to come and have a drink with us one evening. The Bortolinis were originally Russian but had wisely settled in Tuscany before the revolution. Their daughter Lily and Austen’s cousin Pat had fallen in love when the New Zealand Division was there and after much bureaucratic effort (though several Kiwis had joined Cousin Pat in wishing to marry an enemy alien) the marriage went through and the family became Bortolini-Young.

George was now head of the family and though the cousinage was getting a bit thin it seemed right to get in touch. It was not a very successful evening. George seemed wary of us and talked only of the vexing theft of paintings from his chapel and whether we could get him a New Zealand passport.

Still in honeymoon mode we then paid for St Philip and set off for the United States. Winter weather upset all the schedules. We had to take a bus across the peninsula to Genoa and ended up back in Milan but we finally got through the weather to introduce Julie to the flat in Cambridge. The first thing she did was trigger the smoke alarms. She was cooking with the window tightly closed against the cold and suddenly there was a clanging din. Worse, two fire engines arrived and six firemen in their baggy clothing burst into the kitchen. They prowled about checking the flat but Julie soothed them so tactfully that at the end one said, “Thank you, ma’am, for being so helpful”.

When Julie was with me the appeal to hostesses of an unattached male was less and the range of dinner invitations diminished. Having Julie to talk to was much better. On one occasion she arrived with a suitcase holding only a little Wellington soil. She had optimistically filled it with newly-dug potatoes which she knew I loved but they were confiscated in Los Angeles by a sympathetic Customs officer who at least promised to eat them himself. She was disappointed, despite years of familiarity with agricultural restrictions, but eating dinner with her more than compensated me for the loss of the potatoes.

Though no hand with a skillet I had managed fairly well on my own with the Faculty Club for lunch and as a backup for dinner. Before I left my daughters had hastily put together a manuscript cookbook which managed to cover both what I liked and what my modest skills could cook. It sat open on the bench as I worked but the most touching feature was that every recipe started with ‘Daddy’. “Daddy, take two eggs and add a slurp of milk …” or “Daddy, peel an onion in the way we’ve showed you and…” But it was much better when Julie was there and my skills were confined to opening a bottle of wine.

There were the usual sights of Boston to show her. Among the less familiar was the beautiful Kennedy library on its snow-covered point and above all, Filene’s basement. The department store had opened their huge basement to sell clothing at considerable discounts. Their stock was men and women’s wear obtained from good shops in Boston and elsewhere who no longer wanted to sell small quantities or remainders. The principle was that everything was offered at half price; if it did not sell in a week or two the price was reduced to a quarter and then if it still had not sold it simply disappeared.

This left a buyer with a dilemma. Buying a good coat at once left a nagging doubt that in another week the price would have halved again but the experienced Filene’s buyer quickly learnt that delay was not worth the likelihood of losing it altogether. I went on occasional Saturday mornings and, weighing the possibility of some good English shirts, was always fascinated by the deep concentration women brought to choosing clothes. They seemed to become totally rapt in contemplating a blouse or top and some stripped down to their bra in the aisle to try on a possible purchase, though a gentleman returned to scrutinising the shirts.

As the academic year rolled on the principal excitement was the fall of Russia’s Eastern European empire. I ate my breakfast of tea and toast absorbed by the lengthy reports in the New York Times until the bell rang for prayers at 8.40am. It was doubtful that anyone still responded to this call but its continuance testified to the moral earnestness which had replaced prayer in Harvard. In any case, for me as for many others it marked the time to push away the newspaper and get to work.

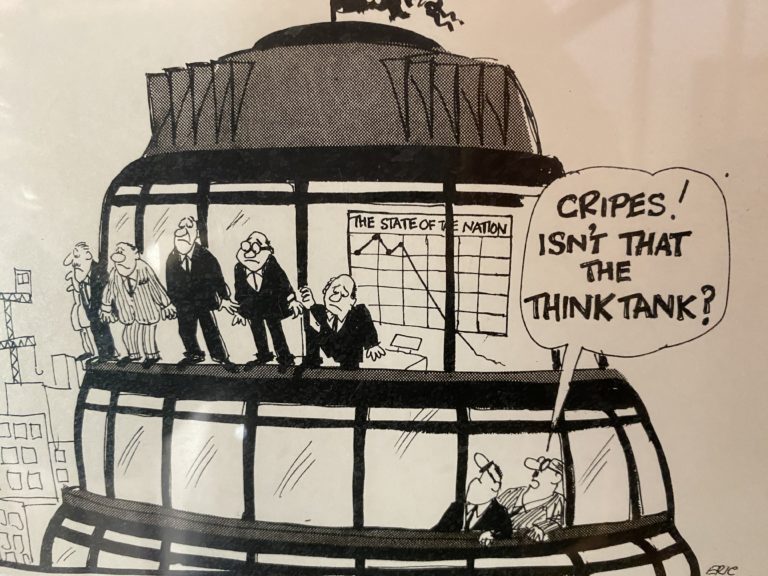

Harvard had a high view of its responsibilities. The story was often told of the president’s visit to Washington during the Woodrow Wilson administration. The butler informed a caller, “The President is not here. The President has gone to Washington to see Mr Wilson.” So events as stirring as the collapse of Soviet rule required a Harvard perspective. A debate was arranged with two representatives from Moscow, two from the CIA and Harvard’s own weighty Soviet expertise to discover why this had happened.

We sat in a room upstairs at the Faculty Club while a fire crackled in the grate and snow fell outside. The discussion quickly became a Russian – American argument but took a surreal turn as we listened to the Moscow people berating the CIA for their naivety in placing any trust in Russian statistics. No-one in Moscow, they said, believed a word of what the government said and the CIA in its innocence had missed the accumulating signs of trouble. The CIA people defended themselves rather lamely. The gathering came to no clear conclusion other than to bring home to me how the familiar world of the Cold War had been stood on its head.

There was a sadder side of East Europe’s liberation. The fellows had a formal breakfast from time to time to entertain anyone of interest passing through Harvard. This was interpreted broadly, with the discussion often continuing from nine to eleven. When we asked the new Czech foreign minister the talk was one of rejoicing; we were eating with the first member of a democratic Czech government since shortly after the War. He naturally agreed but then he made a different point. He said how exciting it was for the young who could now live the life they wanted but for someone like him the years of his youth had been stolen and now could never be recovered. He stared in silence at the tablecloth in front of him.

The approach of spring was making itself felt in the mud everywhere when my phone rang early one morning. It was the State Services Commissioner in Wellington to ask me, with the Prime Minister’s approval, whether I would let my name go forward to be Secretary of Defence. I looked at the round red ball of the sun rising through the mist and brooded. I had never thought much about defence but the principle of public service was that you went where you were asked and no-one had suggested anything else. So I agreed, flew home briefly for the interview process and back in Cambridge learnt that I had been selected. After two or more years of uncertainty, my future was at last assured.

At Harvard, after a last flurry of demonstrations, the end of lectures and the approaching exams brought the silence of revision. My son however was about to get married, to a classmate met when they were both doing an MBA at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. Her parents had a house on the island of Nantucket and they decided to have the wedding there. Julie and I flew there from Boston. The taxi-driver who picked us up expressed his amazement at having such an exotic fare as people from New Zealand which he thought was somewhere near Japan. When by chance he picked us up a week later when we returned to the airport he was even more amazed, having met thirty or more Kiwis in the preceding days.

It was a merry wedding, more like a country wedding in New Zealand than the staider traditions of New England. After the service everyone gathered on the wide lawn of the house beneath the American and New Zealand flags flying from the tall flagpole. My mother, in her eighties, enjoyed herself hugely, circulating among the guests in a pair of bright yellow Crocs given her for the occasion. The party had no difficulty continuing into the evening, after the bride and groom had left for Turkey, where a distinguished lawyer, attempting to leap over a piano, misjudged and fell into it instead, requiring my brother-in-law, Neville, to pacify the management of the Jared Coffin hotel with a liberal distribution of hundred-dollar bills.

Back at the CFIA there was packing and farewell parties. Sitting outside in spring sunshine we listened to the Commencement speeches and the award of degrees. Professor Joe Nye surprised me by producing a diploma in international relations. Given that my colleagues had earned this recognition by working on books, I asked what it was for. Joe grinned and said, “Attendance”.

On my way home the flight stopped in Hawaii and I discovered that my political troubles were not over. Julie rang me to say that members of the press gallery had told her that there were covert moves underway to quash my appointment. We agreed that it might be wise to pause for a few days until the situation became clearer. In the meantime, I suggested she talk with my lawyer, Ian McKay.

So I went to Molokai, riding a strong-willed mule down the steep cliff to the old leper station, trying not to look at the surf breaking on the rocks far below whenever it stumbled. Safely down I moved around shaking the gnarled and twisted hands of the remaining lepers who were cured but preferred to live out their lives in the familiar settlement. Memories of their hero, Father Damien, were everywhere, where he had died of leprosy, the church he had built and the ground outside where he liked to sleep.

On the big island of Hawaii this inspired me to look for other churches the saintly carpenter had built. He thought that Hawaiians would not be entirely comfortable shut off from Nature by wooden walls. So the inside of his churches were painted with palm trees and a riot of greenery. I set off to look at one and was surprised to see the church coming along the road to meet me. Kilauea had erupted again, opening a new vent in its side, and the little church was being moved to save it.

Further on a flow of lava was running across the road and down to the sea, making glowing red pillows of rock in the water as it rolled off a cliff and into the sea. Once again southern Hawaii was enlarging itself. A state policeman at the edge of the flow discouraged us from moving too close (later in the week he died from inhaling the fumes). Even so a few motorists and I, standing as close as we dared, felt we were watching an eruption almost from the inside. A stone tossed a few feet on to the cooling rock in front of us would reveal the sinister red just below. The valley in front of us was a braided river of lava, moving sluggishly. From time to time it would reach a clump of dark trees which burst into flame like a torch; at other times the grey skin on the flow would break apart to reveal hellish flares of orange-red light.

When I got back on the plane to continue my journey home my mood was far from that of the Australian novel which opens with the joyous exclamation “Unemployed at last!” I had gone to Boston on this flight unemployed and coming back was still unemployed. There did not seem many promising openings for someone in their fifties. I understood from friends in the Cabinet that the Prime Minister’s ambitious deputy had organised a covert veto of the appointment when the Prime Minister, Geoffrey Palmer, was at home in Nelson laid low by the flu. As an act of personal dislike it was surprising in a Government which had promised that political influence in public service appointments would be open and declared. It was even more surprising that the State Services Commissioner had not held to his own recommendation, privately agreeing to withdraw it and make another. Ian McKay wrote to the Cabinet to say the process was very likely illegal. When the Solicitor-General was consulted he agreed.

Palmer apologised to me for the upset but it must have been as clear to him as it was to me that this indiscipline by his deputy foreshadowed the larger one which overthrew him a few months later. The result was a deadlock. Press coverage meant the plot was now in the open and the change could no longer be made surreptitiously. Two suitable replacements from the public service both declined to allow their names to go forward in these circumstances and the Ministry of Defence drifted leaderless until an able Auckland businessman, Harold Titter, took the position for a year. He brought a brisk, businesslike experience to the position and kindly asked me to join him as adviser. We worked comfortably together until at the end of the year when the weather changed again and, a little bruised, I found myself in work again.