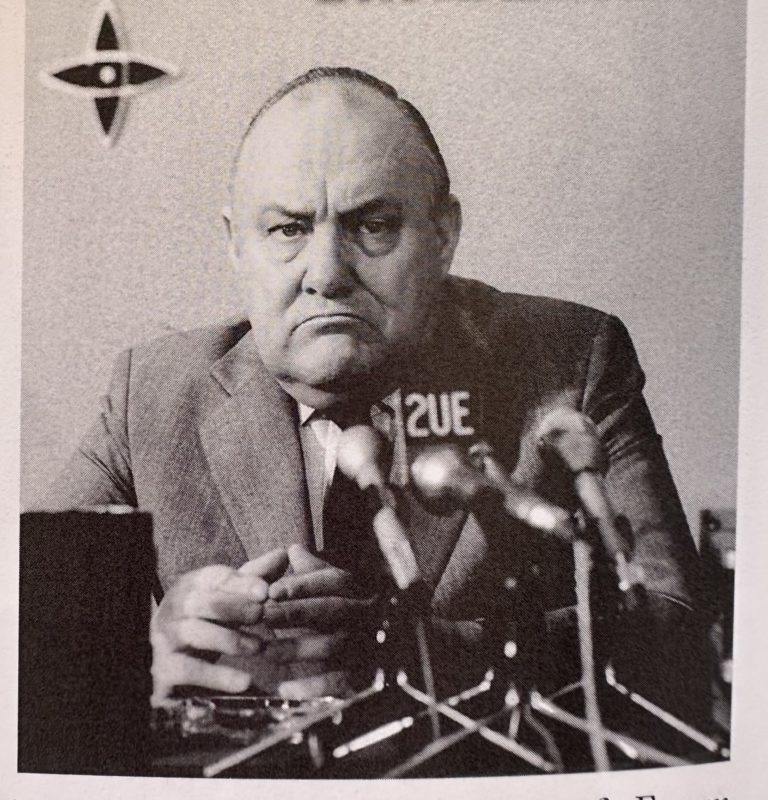

Prime Ministers from Below – Keith Holyoake

Keith Holyoake was under-estimated by every one of my age. It was partly his strangely pompous accent which a private secretary, Bruce Brown, said was the unfortunate outcome of elocution lessons he took to improve his speaking. Though he was intelligent and shrewd, he had a cold manner and a lack of human sympathy, at least to those who worked on the top floor of Parliament Buildings. This housed his office, the Cabinet room and the Prime Minister’s Department which had now morphed almost completely into the Department of External Affairs. We also disapproved of him because he seemed to be a figure from the old Right, a considerable error because he was in fact a politician supremely skilled in the key requirement for successful leaders, governing from the Centre. He had an unerring eye for the middle of the road beloved of New Zealanders and so led for a record twelve years, without attracting either enthusiasm or anger.

My status was too junior to do more than greet him respectfully when we met in the corridors. When I rose to be head of the Pacific and Antarctic Division, I became close enough to become familiar with an odd quirk of his. Submissions sent to him for approval would come back to me neither approved nor rejected but simply initialled KJH. This left the submitter baffled, but McIntosh explained that it simply meant that he had seen it and was not ready to take a decision.

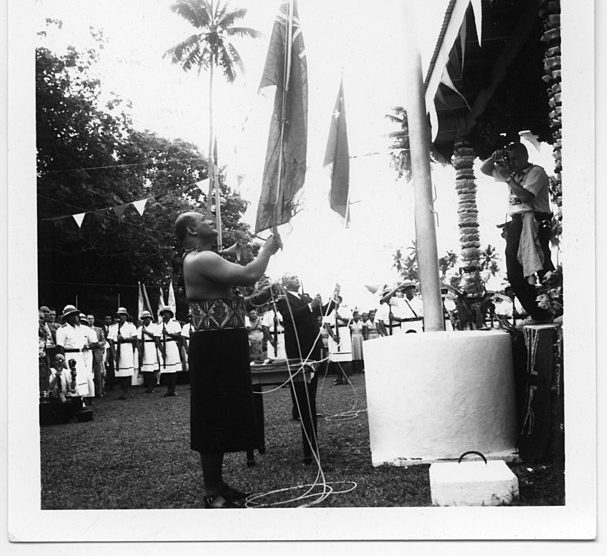

When he made up his mind, though, he was robust in sticking to and defending it. This caught my attention at the end of 1960 when he had just been elected but had not yet taken office. We had by then made considerable progress towards Samoa’s independence. It was not especially popular with the New Zealand public, there were some misgivings especially among our overseas friends that Samoa was too small for independence, and it was not too late for a new government to halt or slow the process. But in the three-week interregnum between governments Holyoake made a point of writing to the High Commissioner in Samoa to say that his government would make no changes in the timetable for independence. I was in Samoa then and it was my first hint that Holyoake was not what his manner suggested.

In the progress of decolonisation the next step, and much bigger difficulty for New Zealand, was what to do about the Cook Islands, a widely scattered group of small islands, some of volcanic origin and some coral atolls, with a total population of not much over 25,000. We worked out an answer called ‘free association’ which, as it said, meant that the Cooks would have self-government with continuing assistance from New Zealand – but they were free to vary the arrangement or move to full independence whenever they wished. Holyoake approved it and we set to work on the details.

No-one else had ever tried it, there were obvious risks and no lack of critics, both international and at home. Some of Holyoake’s Cabinet colleagues, even Ralph Hanan his most liberal minister, thought it was premature and should at least be approached more slowly. The chairman of the Foreign Affairs Committee, Daniel Riddiford, thought we were Communists, even though I often saw him at Mass on Sunday mornings. A number of Cook Islanders in New Zealand, all of them in marginal seats as Holyoake said philosophically, became convinced that a new government would take their land and began a noisy agitation in the Auckland papers.

Standing in his office one morning I made an awkward expression of regret for the trouble we were causing him. “Don’t worry about that, boy”, he said, putting his hand on my shoulder, “It’s my job to handle that”. And he did. When the British, American and Australians all called to urge a halt to our plans he simply told them that New Zealand was too small to stand against the tide of world opinion – a wise view overlooked by his pupil and admirer, Robert Muldoon. Even so public disquiet was reflected in the parliamentary battle over the Cook Islands Constitution Bill where there was an unprecedented debate even over its third reading.

His comfortable political skills attracted admirers, principally the young Robert Muldoon. When he planned his first coup to overthrow John Marshall, the leader of his party, he went to Holyoake as the revered elder. “Have you got the numbers, boy? I don’t think you have”, was the response. And he hadn’t. He did his arithmetic more carefully next time and approached Holyoake again. This time the answer was positive and that was that.

Memories of Holyoake continued to have an influence on Muldoon throughout his own time as Prime Minister, though his combative and impatient temperament prevented him from achieving his predecessor’s calm mastery. From time to time, when he thought I needed it, he would pass on ‘Keith’s’ helpful advice on things like how to get a good night’s sleep (“don’t worry, it may never happen’).

He was saddened when Holyoake died and I offered to write his speech for him, as he usually preferred for large public occasions, but he felt that this was a duty only he could perform. He took some time over it and it led to a bout of nostalgia as he grappled with it, talking to me of the good old days when he was Holyoake’s Finance Minister and the economy was so tightly strapped (though he did not put it this way) that any economic difficulty could, he claimed, be quickly fixed by a talk with Jack Acland of the Wool Board, John Ormond of the Meat Board or Tom Skinner who headed the Federation of Labour. His speech when delivered in the cathedral was not moving but heartfelt. The same was true of those who stood in the streets as the cortege went by, displaying, not grief as was the case with his successor’s funeral, but respect.

As a gesture to his mentor, Muldoon nominated him to be Governor-General. Many, including allegedly the Queen, felt it unwise to choose as her representative someone with a public political commitment. The network of informal conventions, like political neutrality for some offices, which sustained the Westminster parliamentary system were of no interest to Muldoon and his carelessness about conventions, not easily replaced, did some damage. All the same, I suspect he had a lingering discomfort over Holyoake’s appointment.

When we were once travelling by car in Singapore, I pointed out an impressive building (it had become the National Museum) that had been put up by a New Zealand Prime Minister, Frederick Weld, who had become Governor of the Straits Settlements. Suddenly I had Muldoon’s interest. “Was he Governor before or after becoming Prime Minister?” When I pointed out that it had been in two separate countries Muldoon lost interest. His train of thought was clear. We drove along in silence for a few minutes before he suddenly said, “You know, they made an awful fuss about Keith’s appointment”.

When Holyoake was on his way to London to kiss hands, I had to make arrangements for him to break the journey in Singapore. Lee Kuan Yew was away, and I spoke to Goh Keng Swee, the Acting Prime Minister, to fix a time for us to call. Goh, however, insisted that he should call on Holyoake and arranged for him to stay at a house in the grounds of the Istana. This alteration of the niceties was unusual in the protocol-conscious Singaporeans and Goh noticed my slight surprise. He took me aside to explain how helpless and abandoned they had felt in the days after the split with Malaysia. Holyoake was the first after the British to come to their aid “and we will never forget him”.

Unlike Lange, Kirk and even Muldoon, Holyoake was not given to reminiscences. I can’t recall the occasion, though it must have been unusual, when he told me a lengthy story about his first days in politics. In the early thirties he was contesting an election in Motueka. He bought a little second-hand Morris car and for a long day drove all over the electorate, ending up at a meeting in his home town. The hall was full and though he was tired he thought he had made a good speech. When he finished, a man stood up and said, “I move a vote of no-confidence in the speaker”. Holyoake said he stood there while people he had known all his life looked at one another and then hesitantly began to raise their hands. When there were some even from the rugby team he coached he lost his temper. Looking at the sea of upraised arms, at a time when the newspapers were full of pictures of Nazi rallies, he raised his own arm, shouted ‘Heil Hitler to you too’ and walked off. Despite this he was still narrowly elected and perhaps this increased the relish with which he told the story.