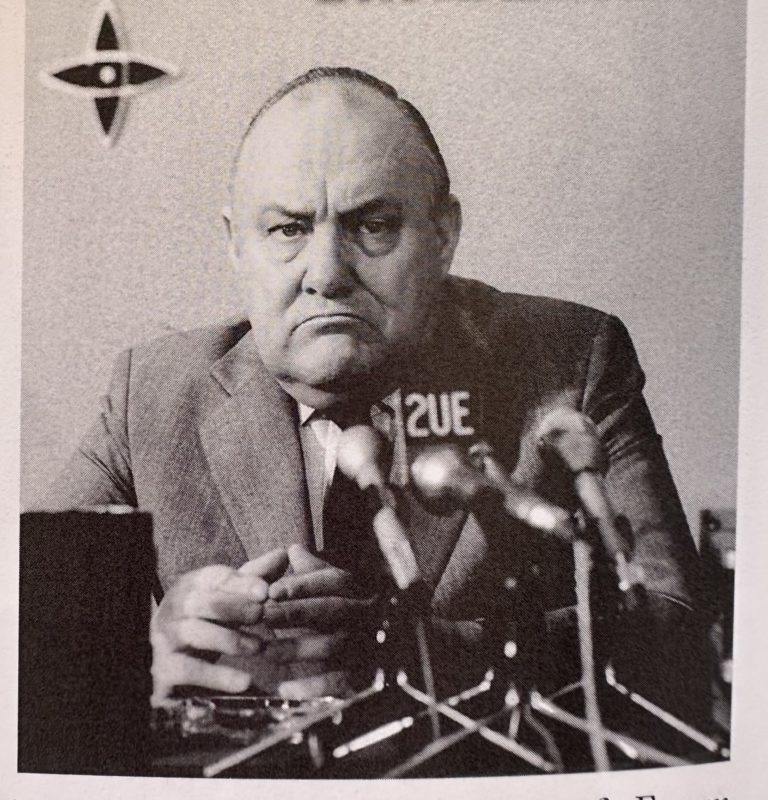

Prime Ministers from below – Norman Kirk

Norman Kirk was the outline of a great Prime Minister that was never quite completed. He was an impressively large man, affectionately known as Big Norm, with impressive abilities. He had great charm and intelligence, was an instinctive good judge of people and issues and had that wariness of his colleagues which seems required in those who run the Labour Party. But these strengths were only on display for his first year in office. From the beginning of 1974 his failing health and energy led to him to shed the burdens of government, by more frequent visits to places like the Chatham Islands, and to a suspicion verging on paranoia that he was in danger of being ousted by his colleagues.

As often seems also to be the case with Labour Governments, he had a strong and widely-respected Finance Minister in Arnold Nordmeyer who was himself unlucky not to become a Prime Minister. Most of the rest of his colleagues apart from a Minister like Joe Walding were, as is traditional in New Zealand, of little note. One afternoon I had to accompany him down to the chamber before the house began. He stood in the doorway looking at the Government benches and said, perhaps to himself, “I don’t see my successor here”. He did in fact see Bill Rowling but his point was a deeper one and was true.

He could be disconcertingly frank about other Cabinet colleagues. His office was still the one on top of Parliament Buildings from which Peter Fraser had run the war and still had the large wireless from which he had listened to the BBC. The legend grew up among journalists that from his desk Kirk liked to shoot pigeons in the light well outside, but I never heard any shots even though I worked on the same floor. I went there with a paper one day. Kirk was talking on the phone but beckoned me inside. He hung up and without preamble said to me, “That woman is such a liar she lies even when there is not the least need to”. I knew the minister he meant but this seemed a rather frank comment to someone not in the inner circle.

Like many heads of government, before and after, he was surprised when he first came to power by the difference between the ready agreement given to any of his instructions and the difficulty of getting them actually carried out. He said once that when he came into office he found a row of shining levers on his desk. He felt a sense of power as he sat pulling the levers but when he looked under the desk they were not connected to anything.

If that was ever true his powerful personality would have quickly overcome it. In his prime, the year 1973, he was energetic and beguiling. He chaired the meeting of the ANZUS Council that year and after lunch he said to those still lingering, ‘Will the council please come to order’ and said to me with a grin, ‘I haven’t said that since I was mayor of Kaiapoi’. He was squarely in the tradition of working-class representatives –as it turned out the last of them. He had left school after the sixth standard and always described his profession as ‘stationary engine-driver’ though it was clearly not his skills at a winch which propelled him into local body and then national politics. His understanding of economics was scanty even by the standards of other New Zealand politicians but his approach to any problem was practical and down to earth and when he said things like having had a ‘gutsful’ of waterfront strikes it was that bluntness which endeared him to the public.

Although he was a close friend of my father-in-law, Austen Young, I first met him as Leader of the Opposition when he came on a visit to Washington. On these visits he always stayed with an American naval officer, Doug Maddison, whom he had met at the American Deep Freeze base in Christchurch, and his impatience with security was a headache for his Washington hosts. He came to dinner with us in Bethesda. While still shedding his coat in the hall he was bailed-up by my son who as a New Zealander born in New York wanted to know whether he should seek to become Prime Minister or President. He laughed and said he doubted his advice would be helpful: “I’ve had two goes and can’t even become Prime Minister”. He was an easy dinner guest, talking about his weight reduction difficulties – “I’ve only to look at a slice of bread to gain weight” – while passing his plate to Julie for another large helping.

His marriage, at least when I knew them both, was a running battle and so more interesting than those of other Prime Ministers. He and Ruth married not from the dawn of love but for an equally traditional reason: as Ruth said cheerfully, “the bull jumped the fence”. They were both strong-minded and so the bouts of warfare were brisk. A camera crew arranged to visit them one Saturday afternoon to film the Kirks at home. My father-in-law arrived early to lend a hand and found a battle in progress, with Ruth shouting and throwing plates and wall decorations at her husband. While he was ducking missiles himself, Austen was alarmed to see the TV crew with cameras coming up the path. There was just time to restore peace and sweep the shards hastily out of sight for the front door to be opened on a scene of domestic tranquillity proper for those in public life.

I rather liked Ruth. She was no fool but her behaviour could be erratic. She found life in Wellington lonely and she felt she was being neglected by Norm. This was noticed by Joe Walding, a sharp observer who spoke to me years later of the perils of a Prime Minister and his wife living in different cities.[1] “Look at the bastard,” she said to Julie at a Government House reception, “he’s going to walk right past me.” She once asked if Julie would accompany her on an official visit to London. She was embarrassed at being the only woman in the party on these occasions, going to the airport lavatory with six men waiting outside and finding them still standing patiently beside the entrance when she came out. She found official life generally trying, I think, but she was tough-minded and adapted. Caught with an unexpected requirement to speak, she told Julie, “I gave my chat”, which has passed into my family’s language.

The last year of Kirk’s life saw almost a complete if unofficial breach of relations. Norm said that she would no longer cook his tea and his makeshift meals of fish and chips and greasy ham may have accentuated his heart trouble. This first manifested itself in the heart attack he had in India at the end of 1973. This was hushed up but his health began a steady decline, not helped by his resolute refusal to get good medical advice; old-fashioned in many things he had that old-fashioned dread of “going under the knife”. In May he had the arteries on both legs stripped, an extraordinarily bold move even for a healthy man. He never recovered. Some weeks later he went to Auckland to consult someone else. He went by train, partly because it was easier for him and partly because his weakness would not be shown up at the airport. Only Austen and I escorted him on to a sleeping carriage for the overnight journey. He walked awkwardly and he sat with relief on the bed, sweating heavily. I thought then that I was looking at a dying man.

The end came in August. He went at last to a coronary expert who told him he had a week to live. His dominant fear seemed to be, not so much his pending mortality, but that the Labour Party would find out and he would be displaced. He admitted himself to the Home of Compassion, gathering his failing energy to be photographed striding vigorously through the door. He died there a week later as predicted, alone but peacefully, watching the police drama ‘Softly, Softly’ on TV.

Poor Ruth wept hysterically. The Home of Compassion telephoned her to come quickly but the garage door was stuck and she tugged at it in floods of tears. By the time a passer-by had helped open it and she had got to the Home Norm was dead. We were telephoned after nine and went to the house in Seatoun, pausing only to seize a half-empty bottle of the tranquiliser Valium which had laid forgotten in the bathroom cupboard.

A small group including the Governor-General and his wife (who in the practical New Zealand way brought a fruit-cake with her) and two or three Ministers who had been friends of Norm. No others came, politics is a chilly business. Ruth was still crying helplessly and Julie and Nellie Rata, wife of the Minister of Maori Affairs, went upstairs to put her to bed. Despite the Valium Ruth could not be calmed until finally Nellie got into bed and held her in her arms until she went to sleep.

Early next morning we were about to leave to gather my father-in-law from the airport when Ruth rang to ask if we would look in at the Home “to make sure Norm is alright”. I did, expecting to see Norm perhaps lying before the altar in the chapel but he was lying on his bed, still in pyjamas, and looking the best he ever had, like a Roman senator carved in marble. For all the sadness, the dignity and stillness gave a hint of relief that for him the difficult struggle of life was over.

As his executor Austen went straight to the Prime Minister’s office and opened his safe. There was not much in it. Some pictures were burnt in our dining-room fireplace but the surprise was a leather bag which turned out to hold around $55,000 in cash. Declaring such an unorthodox bundle was a problem in winding up the estate. Austen, a lawyer of great common sense, handed the bag to the family when gathered and said, ‘You’ll have expenses for the funeral so take what you need.’ This was done (rumour said that Ruth bought an emerald ring) and the bag, much reduced, could be swept unobtrusively into the rest of the estate. No evidence was ever found of how the money had been collected or what its purpose was. The most plausible speculation was that it was Norm’s escape fund, the backing for a dream of escaping some day from the burdens of office.

His funeral saw a great outpouring of grief but there are few traces of his influence today, either in New Zealand or the Labour Party. His influence did not live on in his Party, he founded no political dynasty. Indeed, after him his Party and indeed the New Zealand economy changed to become unrecognisable. On the tenth anniversary of his death I was in Papua New Guinea with David Lange and I asked the Prime Minister whether he would like to send a message home to mark the occasion. He looked at me in astonishment at such an odd suggestion. Kirk no longer caught the imagination of the more middle-class and university-educated people who had moved into the Labour Party.

He was no economist and did not have to be since his brief term came at the last of the comfortable years when New Zealand’s agricultural surplus could pay for everything else. He was a social conservative, uninterested in women’s rights or other changes to the social structure he had been used to. His sturdy practicality began to reflect and focus on New Zealanders’ increasing impatience with union dominance but time did not allow him to do more.

Kirk’s interest in foreign policy has left deeper tracks. His knowledge of the world was not large and arose more from instinct than study but he found a natural partner in Frank Corner who had just become head of Foreign Affairs and Frank’s skill helped shape and point the Prime Minister’s thoughts.

He started uncertainly. By the end of 1972 when he took office the way was clear for the country to remove an increasingly tiresome anomaly and recognise the Peoples’ Republic of China. Immediately after taking office was the time to do it but then mysteriously he had second thoughts (I suspect the very competent Taiwanese representative worked on him). He decided it could wait until his second term until Frank persuaded him of the folly of delay,

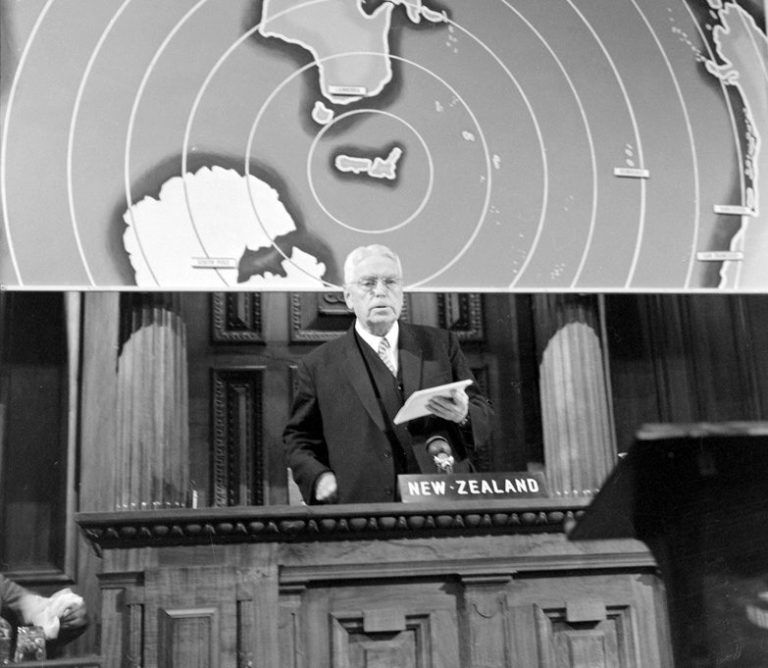

The Kirk-Corner alliance came into full bloom over public concern about French nuclear testing in the South Pacific. France was still testing weapons in the atmosphere and the fallout drifted over New Zealand and small quantities of strontium began to show up in our milk. Diplomatic and other protests were mounted, with the usual lack of results until Frank suggested to him that he send a New Zealand frigate to “observe” the tests in French Polynesia. The voyage attracted worldwide attention and after a pause the French announced that they would halt atmospheric testing.

He was one of the first to begin to think about the longer implications of the post-Vietnam world. He had a Churchillian breadth of vision and a Churchillian vagueness about the detail. His first impulse was to explore the possibility of a regional association linking the Western Pacific from Hokkaido to Invercargill and despatched people like me (head of the Asian Division) to test the views of countries like Japan. Everyone was polite but there was no enthusiasm. Norm had seen that there were now some interests linking such a huge geographical span but they were still too shadowy for practical diplomacy.

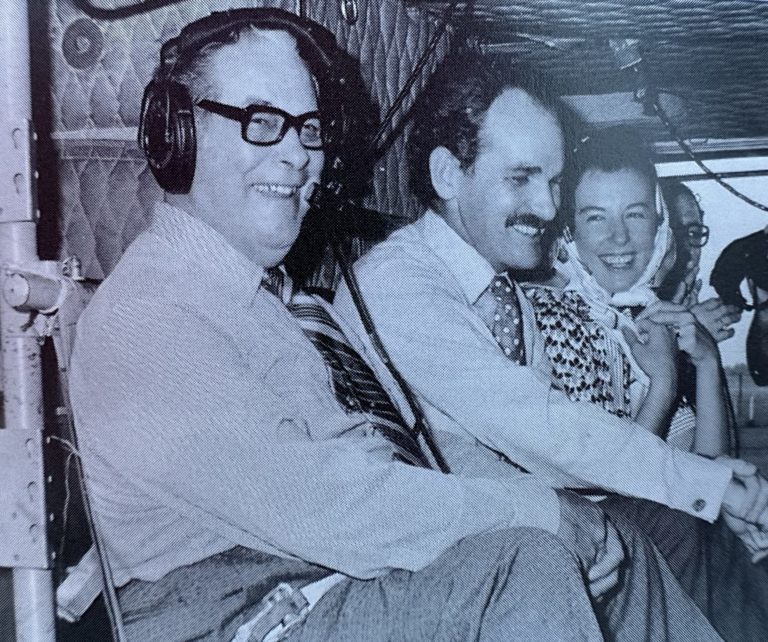

Instead, he lowered his vision to the newly-established group of five Asean states in South East Asia, our closest neighbours after Australia. He grasped at an early date that this association was here to stay and in doing so laid a major plank of our present foreign policy. Towards the end of 1973 he made a tour of South East Asia and India. In the last we had a brief glimpse of Norm’s economics. He visited a factory in Bangladesh that made porcelain dunnies and though we already had a firm in Temuka that made perfectly good dunnies I was instructed to see how we could facilitate more imports.

After that we saw more of the new Norm as he became convinced as he moved through the region that New Zealand should be quick to forge links with the Asean grouping of five countries, now with a growing prosperity and confidence after the end of the Vietnam war. He had a long conversation with Lee Kuan Yew in Singapore and Lee ordered the transcript to be circulated to his Cabinet. Years later Lee would recall to me how impressed his was with Kirk’s vision. Kirk had the force of character to translate more of it into practicalities but his energy failed and his time was too short.

[1] He was thinking then of David and Naomi Lange.