Prime Ministers from Below – Walter Nash

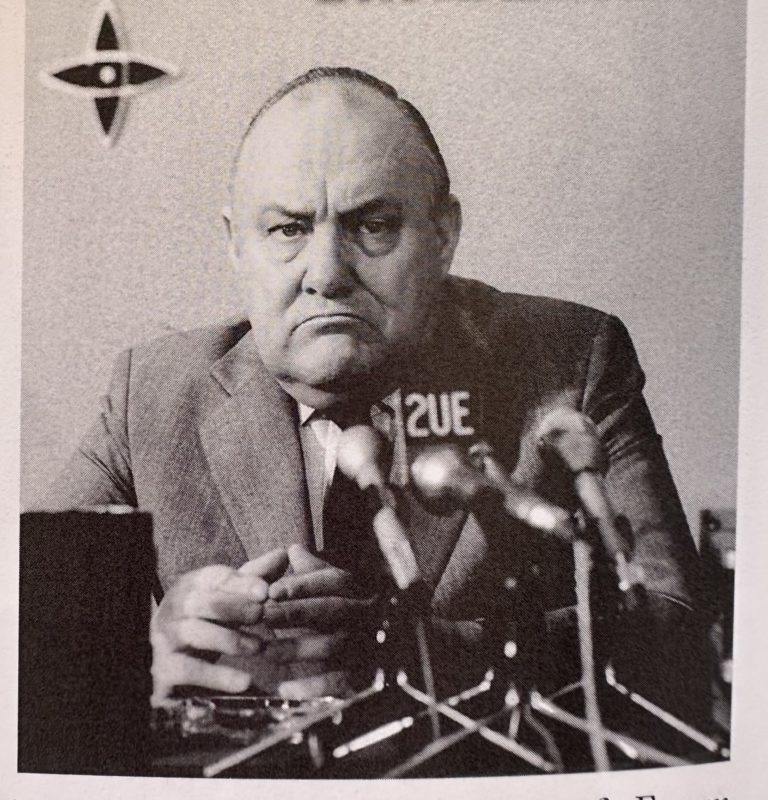

Walter, as he was universally known to those who worked with or around him, radiated a sunny self-esteem. Troubles never seemed to crack his confidence in himself. He was a committed Christian, wearing a gold cross on a chain across the front of his increasingly expansive waistcoat, leading his subordinates in Washington to hum from the hymn “With the cross of Jesus going on before”. Everyone who worked with him felt the urge to laugh at his idiosyncrasies but without any sting. President Roosevelt who was a little irritated by Walter’s urge to brief the American press after every meeting of the Pacific War Council, teased him gently about his self-appointed role as the Council’s spokesman. He enjoyed speaking on the Washington circuit about New Zealand’s pioneering socialism, drawing much on his book, New Zealand, a Working Democracy, a book mainly written by Bruce Turner who had been posted to his staff to do this.[1]

For all the irritations he caused he was widely respected. He was Peter Fraser’s ideal deputy, loyal, hard-working and effective. He and Fraser together ran New Zealand’s war effort and Nash with the help of an able Secretary to the Treasury, Bernard Ashwin, ended the war with New Zealand’s finances in much better shape than they started. Fraser was sometimes annoyed by Nash’s tendency to talk too much, especially to the international press, but otherwise there is little sign that the two ever quarrelled.

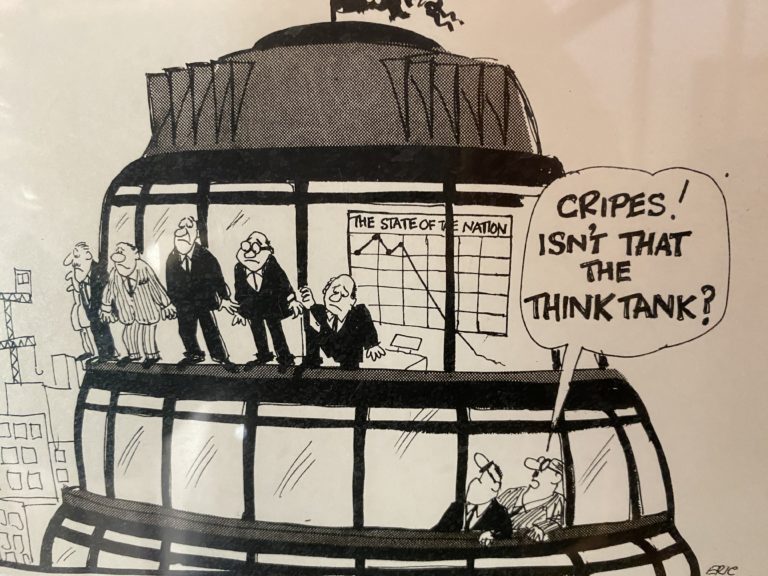

His subordinates were more easily irritated. The main cause as he got older was his famous indecisiveness. On a table under the window of his office when he had become Prime Minister was a large stack of files known to us all as the ‘compost heap’. Anything which required his decision seemed to end up there. Occasionally someone, usually a Private Secretary, would be invited to help him “turn them over”, a ritual which always resulted in stacking the files in a different order but no further action.

It was probably dread of the compost heap which led to one of my first tasks in the Foreign Service. It was a submission seeking approval for spending aid funds on the construction of buildings for an Agricultural College in Samoa where I was about to be posted. It was entirely routine, but I was asked to carry it direct to the Prime Minister for fear that otherwise it might disappear into the compost heap and never been seen again. Being Walter, he scrutinised the paper at some length, carefully adding up the columns of figures for himself. Then he asked me why bike sheds were needed. Because of the rain, I said, and he nodded and read on. The minutes ticked by and then he asked me if they were starving in Samoa. He seemed troubled by my answer that it was tropical and fertile. He went into a sort of reverie, saying that if it was left to him he would drop a 1000 pound bag of flour on every village in Java. I stood in a frozen silence, thinking partly at the fate awaiting the Javanese but more because my first assignment looked as if it might be drifting away on a dream. While I stood there Walter suddenly signed the paper and handed it to me with a sweet smile.

His indecisiveness was a source of stories among the young, like his address to the Petone Rugby Football Club. A speech was prepared in the usual way but his Private Secretary, Bruce Brown, drafted another. Walter put both into his jacket pocket, delivered one and then to the horror of his audience, fished out the second and delivered that too[2]. On another occasion, when Nash led the delegation to the UN General Assembly, they were assembled in his suite at the Waldorf Astoria to discuss the agenda. A waiter came in and offered tea or coffee. Walter hesitated, unable to make up his mind, and then said he would have both.[3]

McIntosh complained that Walter always demanded the best people for his staff and then proceeded to do all the work himself. This was also reflected in his costive reluctance to part with any of the files which came to him. When Nash went to Washington in 1943, he was said to have taken half a ton of files with him on the flying-boat. Many were from the Treasury but a considerable number from the Prime Minister’s Department, despite Carl Berendsen’s angry edict that no more files were to be sent to Nash’s office. In later life Carl attributed much of the blame for his stomach ulcer to having to deal with Walter. When he had just arrived in Canberra as our first High Commissioner, Nash insisted on coming to stay with them, despite their having just moved into their house which was only partly furnished. Carl was invited to Nash’s bedroom to help “turn some files over” and found that Walter had brought at least a suitcase-full of files with him. He declined in a rage, but Walter was not discomfited[4].

This unshakeable pleasure in being Walter Nash was accompanied by a monumental indifference to the needs of others. When I last talked to Sir Geoffrey Cox, a few months before he died, he was still angry over Nash’s treatment of him. Geoffrey was a young captain in the NZ Division in Egypt when he was plucked out to serve as Walter’s deputy when our office was opened in Washington. He was a brilliant choice and because of Nash’s absences in Wellington he spent much time as Charge d’Affaires, sitting on the Pacific War Council with Roosevelt and sometimes Churchill. (Nash’s alternations between ambassador in Washington and Minister of Finance were not so much the result of his famous indecisiveness as that Fraser was determined to be represented in the US by a Minister and Nash was the only colleague with the ability to do so.)

Over the months Cox became increasingly anxious to return to his division, now fighting in Italy. Nash was naturally reluctant, but this was finally agreed and on his last night Cox arranged to take his wife to a farewell dinner, the wartime separation carrying the threat that they might not see one another again. Then Nash took him aside to say that he had to attend a reception that evening. He did not want to bother his driver; it would not take long and would Cox pick him up afterwards. He waited and waited but Nash did not emerge until 9.30. His farewell dinner was ruined and so was any fondness for diplomatic life. When McIntosh enquired whether he would be deputy in the embassy we were opening in Moscow his reply was “rather curt”.[5]

The same irritation seems to have infected even those who worked on his papers after he had died. Keith Sinclair was chosen to write the official biography and he spent years on it. I took him to lunch in London as therapy but lunch was barely long enough to hear his complaints. Walter kept any and all papers that had been touched by the magic of his ego – including bus tickets, old invitations, thank-you letters, intelligence reports and nine drafts of the speech he made at the UN in 1960. All this was stuffed into what had been Walter’s garage without system or catalogue and Keith had come to feel he was drowning in it. He told me, in what were recognisably the tones of Berendsen and Cox, that he had come to loathe Walter and was not sure he could summon the energy to finish. He did, though, and his irritation perhaps turned out to be an advantage: the book was free of that curse of official biographies – earnest respect.

Of all the exasperation felt in varying degrees by everyone who worked around Nash, the foremost authority and bluntest witness was his wife, Charlotte. When they lived in Kidderminster before coming to New Zealand Walter was out most evening on his Church work while Charlotte, who never knew when he would return, kept his dinner warm in the oven. On one occasion he came home especially late, tucked happily into his dinner and, perhaps sensing some constraint in the air, said, “Tell me what you’re thinking, Lottie?” She said, “What I am thinking, Wal, is that I would like to see you in Hell”[6].

Despite this it seemed a happy marriage. While Walter travelled the world she stayed at home in Wellington, looking after the children and the house. Though Fraser liked to take his wife whenever possible, Nash never did. As she became older, not having travelled on Walter’s extensive journeys, a group of her friends in great secrecy arranged a tour of Europe for her, a tour of the ‘Continent’ which was fashionable in the fifties. Walter inevitably came to hear of it and was offended, claiming that he had always promised himself the pleasure of taking her to Europe and would not hear of her going with her friends. The tour was cancelled, he never did anything more about it, and she died without making the journey[7].

She did, however, accompany him when he went to Washington as ambassador. There seems to be no record of how she felt as a diplomatic hostess, but she may have enjoyed it. The Nashes did not drink but their butler made a delicious Old-Fashioned which Mrs Nash and perhaps her husband were persuaded was only fruit juice. She happily urged guests to drink up and it was said that parties at the embassy were very jolly[8].

Walter’s reluctance about drink seems to have faded with time. When he travelled out of Wellington as Prime Minister, it was understood that a bottle of gin should be left tactfully in his hotel room, and when he left the bottle went with him. In those years a group of backbenchers including Norman Kirk liked to meet in a colleague’s room for a drink on Friday nights at the end of the Parliamentary week. At one of these the Prime Minister looked in and was invited with cheerful shouts to join them for a drink. After a necessary demurral or two he was persuaded to hold out a glass. Kirk said they all watched fascinated as the tumbler of gin filled to the top without any sign from Nash for a pause[9]. But though his indecisiveness increased in his time as Prime Minister this was the only sign that he drank even on rare occasions.

[1] McIntosh in my time always referred to it as “Bruce Turner’s book”.

[2] Bruce Brown’s story.

[3] Told to me by Alister McIntosh.

[4] Berendsen’s account.

[5] McIntosh again.

[6] From Colonel Pharazyn who organised the Washington dinner where Mrs Nash was prevailed upon to tell this story.

[7] Bruce Brown.

[8] Frank Corner.

[9] Told to me by Norman Kirk.