A Wonderful Town

There was a heat wave when we arrived in New York in July 1961, with the temperature nudging 100 degrees. Weary after the long flight from New Zealand, we were dazed by the heat, the noise and the crowds as we stepped on to the pavement outside the Hotel Croydon on East 84th Street. About the only thing that seemed familiar was that there was a power failure, and though this was almost a daily occurrence in Apia, it seemed to be causing a sensation in Manhattan. Strangers kept coming up to us to declare how extraordinary it was and ask us if we ever known anything like it and it did not seem helpful to share our Apia experiences.

After two years in Samoa we found ourselves suffering not just from travel but also from culture shock, where it was a challenge simply to cross the road and when going back into the hotel I went twice round the revolving door before I could free myself. Worse was to happen when I was taken for a first visit to the United Nations buildings on the East River. On the way back Quentin Quentin-Baxter, a most agreeable man who was as eccentric as his name, suddenly remembered another appointment and got out of his car at a traffic light, asking me to take it back to his garage. I found myself navigating a large Mercedes in the rush hour through a city I had never visited to find an unknown garage. There was some irritable hooting of horns but I got there, after which nothing else in New York seemed intimidating again.

The immediate need was to find a place to live. House-hunting is seldom a pleasure in a new city but we were lucky. Most of our contemporaries at the NZ Mission and at the UN preferred to live in the suburbs of Westchester County, especially those with children, but Julie and I wanted to be at the centre of things, in Manhattan. That capital of capitalism had some odd quirks, one of which was rent control. Brought in during the war, it still covered a dwindling number of apartments. These gems rarely came on the market but a departing Australian couple led us to one at 14 East 67th Street, between Madison and Park Avenues, which we could just afford.

The apartment consisted of a living-room, kitchen, bathroom and bedroom with an alcove which served as Caroline’s room. It was like living in a ship. The whole flat would have fitted into the ballroom at Papauta with room left over but it was practical, comfortable and was our home for the next two years. There was a superintendent to look after taps that leaked or radiators that sulked, a doorman who helped call taxis for Julie or extricate Caroline’s stroller from the lift and, that great American invention, a coin-operated laundry in the basement.

In New York, even more than in most big cities, living in one place for any length of time fits you into your own local community where being greeted by name as you enter nearby shops brings a small-town flavour to the big city’s impersonality. The centre of our little community was Gristede’s, a grocery and fruit shop on the corner of Madison Avenue. It catered to a much more upmarket clientele than us which meant that gossip from behind the counter was more interesting than usual. The Rockefellers lived in an enormous apartment on Fifth Avenue nearby and though never to be seen with a trolley in Gristede’s their doings were the subject of occasional witty speculation.

When large and very expensive peaches were flown in from Bulawayo Julie wondered who would ever buy them. The assistant leant over the counter confidentially to say, “The Rockefellers are making jam”. Over time Julie herself became something of an adviser on the exotic, called in to explain the use of a mysterious fruit which had arrived, called kiwifruit.

One Saturday morning, when I was there with Caroline in a stroller, we met Ernest Hemingway’s widow. After asking me what I did, she bent down to Caroline to say, “And what do you do, little lady?” Caroline pondered this for a moment and then removed the thumb from her mouth to render her verdict: “I do wees”. Mary Hemingway, perhaps not used to the thoughts of toddlers, retreated.

Within ambling distance of the flat was William Greenberg, perhaps the inventor of the chocolate brownie and certainly its most brilliant exponent. Julie claimed to have lived on his brownies for the whole of her second pregnancy. Even the chemist, which we learnt to call the pharmacist, was interesting, but perhaps more to the FBI than to us. We lived near the Soviet Mission to the UN and the chemists were infallible informants about staff changes because every wife before departing came in to buy the largest possible carton of lipsticks.

In the other direction was the wine shop which would sell to me duty-free. It was before the dramatic rise in Bordeaux prices and the result was that we could afford to drink some marvellous clarets long before we were able to appreciate them. It was like taking three-year-olds to a Bach concert but in both cases there is no harm in starting at the top. Doing so, though, has meant that my drinking life has gone steadily downhill: as a humble Third Secretary I drank better wines than I have ever been able to afford since.

Floating along the street most days were one or two Sisters of Charity who ran a home nearby and were always an angelic sight in their wide, starched headdresses, like wings. Another regular was the man with a billboard with an unexpectedly restful message: the end was nigh but not until several preconditions had been met. Relieved by the delay most people had a greeting for him.

The most energetic and certainly the noisiest neighbour was the fire station on the other side of Park Avenue. It boasted the traditional Dalmatian fire dog which dozed on the pavement outside. When the alarm went and the long ladder truck – so long that there was a man posted at the back with his own steering wheel – left the station and headed towards Park Avenue the dog, from long experience, did not move. But as the ladder slowed to turn on to the avenue it would race up the street and leap on. Then the truck would accelerate down the avenue with the siren rising and falling, the klaxon blaring and the dog barking from the top of the cab. The noise, especially if you were asleep, was unbelievable but to any new arrival New York seemed to rest on a steady background of noise, highlighted by fire, police and ambulance sirens.

It was worth it for the excitement of living in Manhattan. Even the food on sale was different, starting with the surprise that fresh orange juice was delivered every morning with the milk. We learnt that cheese was not just ‘tasty’ or ‘mild’ as at home and the stock of a nearby shop, “Cheeses of Nazareth”, offered a surprisingly wide range of types. Tea turned out to be, not a packet of Ceylon, but a variety of flavours poured out from interesting jars. Coffee, pasta, olive oil and even bread turned out to be new possibilities rather than names. Cuban cigars were available to diplomats. I had never smoked them before and had to fight a little battle with the US Customs to get my box released – even then I had to be careful not to offer them after dinner to American citizens.

Walking to work down Fifth Avenue, looking in more expensive shop windows at things we could never buy, was also a constant pleasure. It revealed a truth about New York. The key to enjoying it was not the skyline or your income but the promise it held out, the fizzing current that gave you the feeling that anything, good or bad, was possible in that city. The limousines and ancient ladies swathed in furs declared New York to be a good place to live if you were old and rich but surprisingly it also turned out to be a good place if you were young and poor, or at least able to live on 67thStreet and shop at Gristede’s.

Sampling the town’s delights was a random thing, dependent often on the kindness of others. We had no money for plays or restaurants and hours at the New Zealand mission were long, often after midnight when there was a task like seeing Samoa through its trusteeship. We did, though, manage to go to Beyond the Fringe when it came to New York. It was a novel experience in every way, from watching the show while eating dinner in the darkened theatre to seeing ‘Sir Alec Douglas-Home’ arranging flowers in high heels. The American audience were unsure what to make of it; when I heard a loud laugh ring out I was surprised to discover that it was my own.

At home we discovered the pleasures of colour TV, unknown in New Zealand let alone Papauta, and sat curled up together on the sofa for hours. The new medium was still not quite word-perfect, so that a boom and microphone would occasionally swing across the top of the screen and one hour-long discussion ended in a fight when the teapot everyone was sipping from turned out to contain whisky and not tea. The screen abruptly went blank and we were entertained with music for the rest of the hour.

In the well-established American tradition there was a Hospitality Committee of well-born New York ladies to welcome newcomers and through it we made friends and excursions to unlikely places like El Morocco night-club with its seats covered in zebra skin, the press room at the New York Times to meet Margaret Truman, the former President’s daughter and press the button that started the presses on their evening run, and an Italian restaurant where the bartender suddenly burst into the Anvil Chorus, walking round his bar and ringing out the melody on his up-ended bottles of spirits. They sent Julie to Best’s on Fifth Avenue for a cot and carry-cot for Caroline and me to the Strand bookshop near the Bowery, a collection of second-hand books so vast that like a dog near dinnertime you began to drool even as the bus drew near.

We found New York’s riches of art and music for ourselves. For three summers we made the trip to the music festival at Tanglewood in the Berkshire Hills of western Massachusetts. With some sandwiches and a bottle of cold white wine we sat on the lawn outside the ‘Shed’ to hear the Boston Symphony and other orchestras and chamber music. If it was late in the season the drive home was itself a pleasure as the trees of New England began to flare with colour.

At home we made regular trips to the Cloisters at the top of the island to visit the beautiful unicorn tapestries and other medieval wonders, especially the dark and uncomfortable effigy of the Count of Urgell. The Metropolitan Museum was close but tended to give the viewer indigestion. We used to go with the admirable intention of looking at only a specific room or school of painting but there were always paintings glimpsed through the next door to tempt you on until the familiar indigestion was back. No wonder Frank Lloyd Wright called it a “Protestant barn”.

Because it was on a more human scale and had the coherence of pieces chosen largely by one man we preferred the Frick, on Fifth Avenue a comfortable stroll from either of our flats. Henry Clay Frick, who built it as his home, was doubtless an unpleasant robber baron but he had a good eye and the money to prove it. His daughter Helen Frick still lived upstairs and I would occasionally see the lonely old woman being escorted to concerts in her own house.

The New Yorker magazine revealed that Sunday afternoon classical concerts were held in the oval music room at the Frick, painted a pale green and hung with Sargent portraits. Baby-minding meant that I usually went on my own but we discovered opera together at the New York City Opera which, unlike the Met, was affordable for people like us. I had never seen opera live before. We started with ‘The Marriage of Figaro’ and when the first act reached its climax and the curtain swept down I was transported and could not speak.

Manhattan, though, was made for walking and in the words of the old song we liked to “walk up the avenue till we’re there”. We walked wherever possible and with the help of the stroller Caroline did too, even in the Easter Parade down Fifth Avenue where she and her mother became a mystery presence in scores of home movies. On Saturdays, sometimes after a warm-up on the swings in Central Park, we liked to spend the morning in Greenwich Village, watching the elderly men playing chess in Washington Square and eating Italian sausages cooked on charcoal stoves. There we saw a man shot and his body lifted into an ambulance. When we came back a policeman was methodically hosing the pavement, sweeping the blood-soaked sawdust of a man’s life down the gutter.

The NZ Mission was busy that year, with a special as well as the regular meeting of the General Assembly and, shortly after my arrival, our last appearance in the Trusteeship Council, to see Samoa off the international books and into independence. Anti-colonialism was coming to dominate the agenda. The membership had dramatically increased with an influx of newly-independent countries. They were impatient, feeling that the UN’s traditional approach did not reflect the right sense of urgency about the abolition of colonialism. They were fearful, fearful of the economic and military power of colonialism and determined to use the international institutions to bring it down.

This was something the UN could do. Often derided as a talking shop, the General Assembly building which its architects had thoughtfully shaped as a loudspeaker could focus and broadcast the emerging consensus on colonialism. As I sat for weeks in the Assembly’s Fourth (colonial) Committee, listening to heated and endlessly repetitive denunciations of the colonial powers, I could console myself with the thought that this had been started and partly shaped by Peter Fraser, the New Zealand Prime Minister who was responsible for the chapters on colonies in the UN Charter.

Apart from this the main excitement in 1961 was the visit of President Kennedy. A kind of royal box was arranged for Mrs Kennedy to hear the President’s speech to the General Assembly. Mrs Holyoake, our Prime Minister’s wife, was invited to join her and she generously passed the invitation to Julie. We had earlier discovered another surprising feature of New York, the retail outlet, where Guccis and Chanels could be bought new at reduced prices. By a lucky chance Julie had acquired, at a price low only by Rockefeller standards, a cream-coloured suit perfect for this occasion. If Jackie Kennedy was surprised to find that her guest was a beautiful twenty-five-year old in a Chanel suit instead of an elderly politician’s wife she was far too good-mannered to show it. Sitting beside Mrs Kennedy and her sister Lee Radziwill Julie had a splendid time. When the speech was over everyone moved through to meet the President and have a congratulatory drink. Julie, however, found herself deftly diverted and back in the delegates’ lounge. Mrs Kennedy was taking no chances.

As the weather got colder we bought a car, a tiny Fiat 600, always called the Bambino. We hardly needed anything larger and its size meant that we could often squeeze it into a parking slot outside the apartment. It had other advantages too. Dashing into the New York Public Library to get a book I left it parked for a moment on a fire hydrant. When I returned there had inevitably been a fire but the fire crew had cheerfully picked up the car with Julie and Caroline inside and carried it down the street. When filling it at a gas station people would ask, “Did you make it yourself?” but there was a more memorable put-down late one night when filling the car at a big gas station beside the Delaware Bridge. The petrol, tax free, came to four dollars but when I handed the attendant a ten dollar bill he looked at the long walk to and from his office required to bring the change and told us to drive off.

With the car we could for the first time move off Manhattan Island, visiting colleagues who had half-acre gardens in Scarsdale, marvelling at the fall colours and in my case struck by an unusual smell which turned out to be the smell of fresh air. As spring approached in the following year the end of an over-indulgent UN General Assembly gave us the chance for a longer drive. With Caroline tucked into a car seat at the back we drove down the east coast to Georgia.

As we drove south spring came up to meet us. Dogwoods and forsythia recovered their leaves and had burst into blossom by the time we reached Virginia. We learnt that infallible sign of being in the South, not signs identifying the Mason-Dixon line or battlefield markers but the sudden appearance of signs on shops and houses saying NIGHTCRAWLERS. We learnt too how reluctantly the scenery changes in such a large continent. Any long drive in New Zealand went through coast, forest and mountains but for several hundred miles from New York the trees and outlook barely changed.

On the other hand the liquor laws seemed to change from county to county. All English-speaking countries seemed unable to settle the problem of drinking in public. New Zealand was still in the shaky grip of six o’clock closing; crossing Canada your drink was served or removed depending on which province the plane happened to be flying over. Travel down the East Coast, though, set some sort of record. There were places where you could only drink sitting down and others where you could only drink standing up. Sometimes a bottle had to be consumed on the premises, elsewhere it had to be wrapped in a brown paper bag and taken away. All seemed to open and close at eccentric hours.

Like most people we went to see the dream of the South, the antebellum legend rather than the practical reality. States like South Carolina and Georgia gave full measure. We walked up avenues of trees hung with Spanish moss to Greek Revival houses sleeping in the sun. One plantation house had an avenue of camellias and we walked along a floor of pink petals. At Cape Fear we stumbled on a neglected Civil War battlefield with trenches only partly fallen-in and a roofless church in which the wounded had been placed.

In these lovely sites slavery drifted away into the 19th century, along with cotton-fields and crinolines. The South itself still seemed immobile, frozen in shock by the end of the war. The African-Americans we talked to, manning motels and gas stations, were wary and evasive; the other Americans defiant and unable to see any change. It was a jolt for us to make a relief stop at a gas station and see three lavatories labelled Men, Women and Coloured. A hundred years after the triumph of abolition the shadow of race differences still lay over the country. In 1962 the ground was at last beginning to shift but I kept thinking of de Tocqueville’s view that slavery based on visible differences would be peculiarly hard to erase.

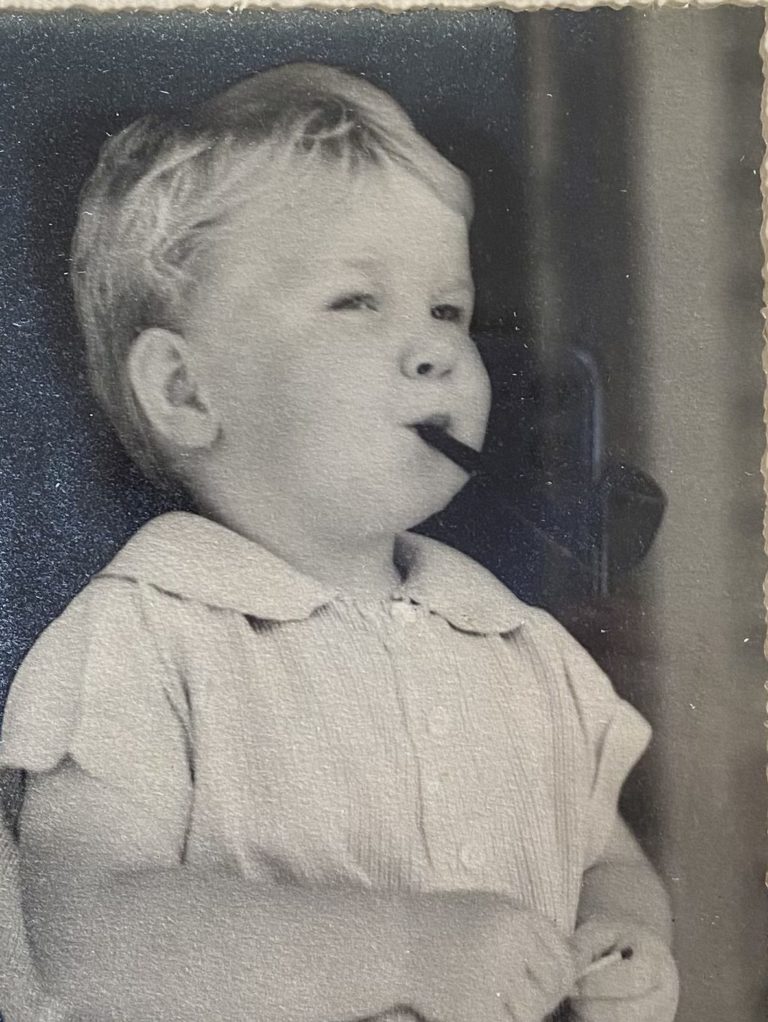

Our second child, Gerald, arrived at the end of May on a day New Yorkers have ever since chosen to call Blue Monday. The birth could not have been more different. On the afternoon of the predicted day he was on his way. We had a leisurely dinner and then I drove Julie to Doctors’ Hospital on East End Avenue. Knowing how these things went I hastened back to the flat to get a book for the long wait. When I returned twenty minutes later there he was, a dark-haired bundle to be viewed through a glass window. A boy was to be called Philip Charles Austen, to meet a selection of family obligations, but when I returned next morning Julie triumphantly waved his birth certificate naming him as Gerald Austen Joseph. It appeared that in New York a birth had to be registered within twenty-four hours and she had seized the chance. I was secretly flattered though the choice condemned me to a lifetime of finding ways to explain that it was not me who had named him.

Julie and the baby flourished and lengthy visits were a pleasure. It was the only maternity hospital I ever attended that did not regard fathers as the cause of the trouble or at least a nuisance, with the possible exception of the Queen Alexandra Home for Unmarried Mothers where Sarah was born and where they seemed startled to see a father at all. Marilyn Monroe was being dried out somewhere else in the hospital and new fathers were not encouraged to call. Otherwise there was nothing to be wished for. I could stay with Julie as long as Caroline’s sitter allowed and lunch would be wheeled in for me on a table with a half bottle of wine while we sat talking and the baby slept in his cot beside us.

He was christened at St Vincent Ferrer, a church on Lexington Avenue, by Father Wu, a Chinese Dominican. His Latin at the font was so Chinese it was difficult to know whether he was following the baptismal service or reading from the Analects, and even more difficult to know when to make the responses. Woze took his revenge some months later. At midnight mass on Christmas Eve, as Father Wu rolled by in procession Woze stretched out his hands with an ecstatic cry of ‘Daddy!’.

The difficulty of having two Geralds in the house was solved by Caroline. Deeply attached to her brother she initially called him Wo-Wo, possibly mistaking him for a dog, and in family usage over the years this became Woze and so fixed that even his son has been known to call him Uncle Woze. Woze was an active child and bit his paediatrician at first meeting. Dr Ginandes marvelled, saying it was the first time a child had bitten him. When Woze went back a year later he seized the opportunity and bit the doctor again. Ginandes said in puzzlement that he had only ever been bitten once before and then looked more closely at Woze: “It’s him again”.

At six months he caught a deadly form of gastroenteritis that was afflicting children in New York. We did not know this, but his listless appearance and inability to keep fluids down required a precautionary visit to the doctor. I was at my desk drafting my instructions for Wellington to approve when the doctor rang to say, “Your boy is severely dehydrated and if he is not is hospital in four hours he will be dead”. I took a quick cab down Third Avenue, picked up Julie and Gerald and in record time ended up at Mount Sinai Hospital.

It was not a charitable institution, at least for me, and the receptionist asked for an assurance that there was $1500 dollars in my bank account. It was doubtful there was even $150 and my assurances to the contrary must have lacked conviction. She telephoned my bank and the Chase Manhattan to its eternal glory lied in its shark-like teeth and said the money was there. Gerald was immediately admitted and made a quick recovery.

I returned to my diplomatic learning curve. Diplomacy like the bar is one of those arts requiring not just study but an apprenticeship, absorbing the skills of your elders by carrying their bag and trotting along beside them. The UN was a good place for this. Milling about between sessions in the delegates’ lounge meant seeing a number of well-known ambassadors in action, not always a suitable sight for the young. But lessons on how to behave were insensibly absorbed. The Australian Ambassador, Sir James Plimsoll, was talking to me when another grandee came up and Jim said, “I don’t think you have met my colleague Mr Hensley”. I glowed at the thought of being regarded by Jim Plim as a colleague but also hoped to remember to practise a little of his courtesy in future. And there was Adlai Stevenson, the American Ambassador, who as a former politician liked to give occasional breakfasts for the young, from which we drew some memorable stories as well as glimpses of how policy worked at the top.

At one, he was asked by one of us why he was always called Governor Stevenson when it was two decades since he had been Governor of Illinois. In answer, he said that Eva Peron had once paid a state visit to Spain. She attended at a grand opera performance in her honour but as she walked up the long flight of steps with Franco the watching crowd began chanting ‘Whore, whore’. Franco patted her arm and said, “Pay no attention, my dear. Why, it is twenty years since I was in the army and they still call me General.”

My ambassador, Frank Corner, was especially good at showing rather than telling. On one occasion he took me to a dinner given for half a dozen senior ambassadors by Narasimhan, the rather lordly Deputy Secretary-General whose lordliness doubtless came from his membership of the elite Indian Civil Service. As the baby I sat at the end of the table and listened. The talk turned to wine and Narasimhan produced a wrapped bottle of something, by its shape clearly claret, for Frank to identify. The table fell silent as he took a few sips and suggested it was Chateau Haut Brion. Narasimhan invited him to try for the date. Frank took another sip and said 1955. The bottle was unveiled to reveal just that. There was general applause and the Spanish representative, an eighty-year-old marquis, said that only the aged like himself and his white-haired New Zealand friend ‘too old for other pleasures’ (though Frank was the father of two young girls) who could accumulate such knowledge. Going home in the car I asked Frank how he had managed such a feat. It was simple: he had just bought a case of the Haut Brion, had recently opened it and so recognised the wine as soon as he sniffed the glass.

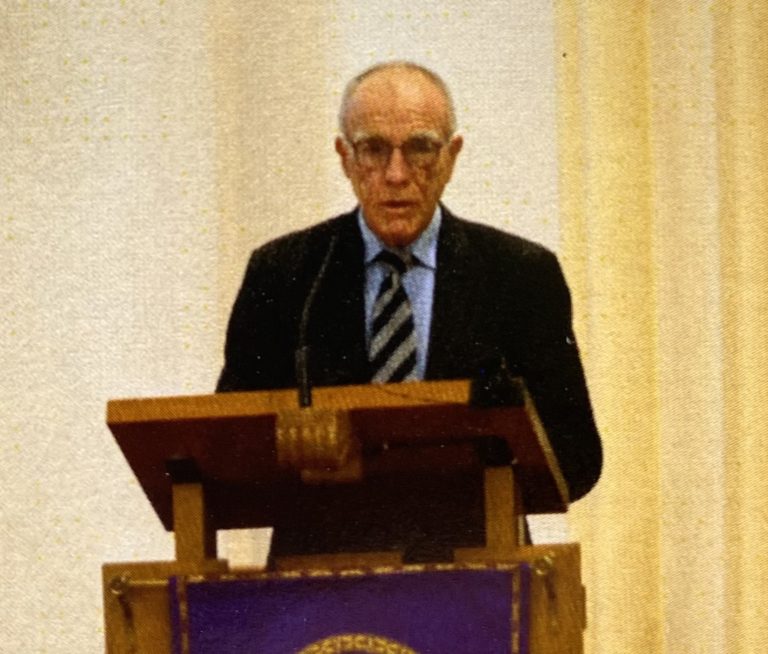

The UN General Assembly convened for my second annual session in the third week of September 1962. Aside from the Prime Minister’s visit the delegation was led by my boss, Alister McIntosh. Proceedings opened with a lengthy and tedious general debate in which a succession of representatives of often repellent regimes proclaimed their undying attachment to democracy, human rights and the end of imperialism. Mac felt that the New Zealand seat should always be occupied and as the most junior I was detailed to sit with him in the somnolent evening sessions.

Quiet conversations were possible and so for several evenings I listened to this unassuming but very wise man. He reassured me by saying firmly that no-one could ever save on a foreign posting. When I told him we had just bankrupted ourselves buying a lovely Tabriz rug he said that when he looked back on his life what he regretted was not what he had bought but what he had failed to buy – a recipe for spending that I took to heart. Beyond that he said something of even deeper significance: in life you will probably get your first choice, what you most want, but not necessarily your second.

Then he mused out loud about the succession as his retirement approached. I sat rigid at being favoured with such confidences as he said Foss Shanahan, his deputy and my ambassador, would probably not do. This was surprising but sensible. Foss was an empire-builder and I knew, but of course did not tell Mac, that the only advice Sidney Holland as incoming Prime Minister received from Peter Fraser his predecessor was “Watch out for Shanahan.” Mac chuckled indulgently about Frank Corner’s firecracker intelligence and concluded that George Laking would have to succeed him. It was an example of the extraordinary frankness Mac could sometimes display, a frankness apparently matched by the reticence of whoever he talked to. It was thirty years before I even told Julie of this conversation.

Mac’s homosexuality was then entirely unsuspected but when it became known Julie told me of her puzzlement when first meeting him in New York. She said without vanity that in her twenties she was accustomed to a little jump of recognition when first introduced to a man but got nothing whatever from Mac. Given how greatly he was admired by everyone who worked for him she was left wondering what was wrong with her.

There was now little opportunity on the East River to talk about anything other than colonialism. Wars came and went like the struggle between India and China in the Himalayas and the unending tragedy of the Congo. None were considered by the General Assembly. Instead the more radical members of the majority were sharpening their weapons, breaking away from the former arrangements for scrutinising colonies as too legalistic and too slow. Conventions and parliamentary procedures were overturned, which was upsetting for the more orderly members, but after careful thought New Zealand opted to work with the future rather than defend the past. As a small colonial power anxious to go out of business we had to step carefully in this maelstrom: we still had the future of the Cook Islands to think of and needed to safeguard the fragile goodwill we had earned. So my instructions were to lie low, not difficult when so many others were crowding on to the floor.

The Cuban missile crisis upended this self-absorbed community. There had been some earlier signs that the two super-powers, the Soviet Union and United States, were beginning to circle one another over Cuba but everyone, even in Washington, was startled by the discovery that the Russians were covertly installing nuclear-capable missiles to threaten the entire East Coast. The usual busybodies called meetings at the UN to “mediate” or “seek a formula acceptable to both sides” but it quickly became apparent that the two powers were manoeuvring in a deadly game and the safest course for the bystanders was not to distract them by some sudden noise.

It had always been assumed that Manhattan was a target in some of the missiles nestling in Soviet silos, but what was theoretical now assumed a new immediacy. We felt not just that we were a target but that the crosshairs were being adjusted. For some years nuclear shelters had been scattered round the city. There was one near us though the opinion in Gristede’s was that it would be of little use in a crisis, filled with Russians from the Mission who would have got advance notice. It had been customary for some years to test the sirens warning of nuclear attack every month. The usual testing day fell in the middle of the crisis and so we were told that the test was cancelled; sirens would now mean the real thing. Inevitably the ban was not complete. I stood in my office looking down Third Avenue listening to the rising and falling of the siren near us and thinking this is, it must be, a false alarm.

It was, but did nothing to diminish the panic buying in supermarkets and the dense lines of cars on the bridges out of Manhattan. Everything turned on whether the Russians would challenge the naval cordon which President Kennedy had placed around the island. This would not be known until the Security Council met that evening. So after lunch I skipped the UN Day concert and walked home. Julie was sitting in the fall sunshine with the children in Central Park. My appearance there in the middle of the working day was so unexpected that Julie said to me, “Is it all over?”, thinking that I might have come home to meet the end with my family.

The two powers showed considerable finesse in ending the crisis – any university course in diplomacy could profitably spend a month looking at how dangerous differences were intelligently managed. The Assembly went back to its preoccupations of which a minor one was to hear a report on Hungary. After the Soviet Union had put down the uprising in 1956 the UN, in default of anything more useful, had appointed Sir Leslie Munro, the former New Zealand ambassador, to supply an annual report.

It was a rather sad sinecure, sad for the helpless Hungarians and sad as a conclusion to Munro’s distinguished career at the UN. By then I had risen to the lustrous height of Second Secretary but still the most junior in the Mission I was detailed to look after Les when he came to present his report. This mainly involved sitting in the Delegates’ Lounge drinking martinis. Les’s capacity for alcohol was as big as his ego and Walter, the longstanding barman, would bring us two enormous martinis, four to the bottle of gin according to rumour. Conversation was not difficult since Les talked only about himself on which he was an expert, but he was hardly into a reminiscence of his time as President of the General Assembly when he would discover that his glass was empty. A purely formal “You’ll have another?” was the signal for Walter to refill his glass while I continued to take genteel sips from mine. After three of these Les would totter into lunch with some other notability while I tiptoed away, leaving a half-full glass on the bar.

This was base-camp stuff, though, in the annals of those who had ascended the higher slopes with Les. Lance Adams-Schneider, a Minister in the Muldoon government, was a fellow MP from Hamilton after Les entered Parliament. On Sunday nights they both sat in the small VIP waiting room at the airport, waiting to return to Wellington. Les, well fortified by dinner, fell asleep and snored so loudly that his false teeth shot out and across the room. It fell to Lance to recover and reinsert them in Les’s open mouth.

In the following summer we took our holiday in a converted barn on Cape Cod. It got off to a rather nervous start. When the Fiat drove into the yard the farmer said there had been a little emergency, a grandson had come down with mumps. My asthmatic childhood meant I had escaped several infant diseases including mumps. Through the hastily rolled-up car window I enquired where I could get a shot and then, without anyone even getting out of the car, drove across the Cape to Brewster and the nearest surgery that could supply an inoculation against mumps. After this everyone, or at least me, could calm down and begin our holiday.

The Cape, not yet built over, had great New England charm. The beach near us was overhung with beach plum trees, the sea was docile for paddling but up the coast the tall Highland Light flashed restlessly at night as a reminder of the cape’s exposure to the Atlantic. We went to the then slightly raffish Provincetown, raffish by New England standards because it sported even more beards than jars of beach plum jam. We took the ferry to Nantucket and passed the President dabbling his feet in the water from the side of a small yacht and he gave us a good-natured wave. In an ancient bookshop in Yarmouth we found the two volumes of Robert Louis Stevenson’s last publication, Vailima Letters, with a handwritten dedication from the author. Most momentous of all, Gerald learnt to walk, wobbling along beside Eva, our Danish help, with a grin of self-congratulation.

Even so he had found this travel rather demanding and as soon as we were home he retired into the closet in our bedroom and sat there in the dark for a restorative period. We were in fact again on the move. The apartment building had been bought by a Mafia-type group who were anxious to get rid of the less profitable rent-controlled tenants. The doorman disappeared, followed by the hot water. No doubt stronger measures would have followed but we took the hint and looked for somewhere else.

What we found was two floors at the back of a townhouse on East 78th Street, between Park and Lexington Avenues. Needless to say it was a financial squeeze but by good fortune the previous tenant had been an eccentric woman who had two monkeys and other pets and this helped with the rent. Nothing was left in the flat whose walls were scuffed and stained but once they had been repainted and we had rented beds, chairs and a dining table, it became rather elegant accommodation.

There were three bedrooms and a bathroom downstairs and a living room and kitchen upstairs. On the first floor outside was a terrace which looked into our garden and, even more pleasantly, into the skilful planting of our neighbour’s, the Secretary to the Navy. Standing on this terrace early one morning Caroline was greeted by Mrs Rogers who asked where her mother was. Since she had acquired the muddled idea that soft drink was gin, Caroline said that she had gone to buy gin. “Mummy buys a lot of gin” she said helpfully. Mrs Rogers concern was ended by Julie’s return completely sober and all was explained.

As relics of its past splendour as a townhouse, the living room had a parquet floor and large fireplace – the last a rarity in Manhattan. A Westchester friend provided some firewood, some firedogs were found (which I still have), but no-one seemed to have heard of a poker. I found a hardware store on Houston Street which was hung with ironmongery and looked promising but after I had repeated my enquiry about a poker three times the assistant beamed at me and leant on her elbow across the counter to say, “I can’t unnerstand a thing you say but I love to hear ya talk”.

That left the garden, turned into a complete mess by the monkeys. It was an oblong walled garden with dreadful city soil and a few trees and shrubs that had survived the simian occupation. The Christchurch boy in me rose up and I laid down a lawn. With heavy watering and a little discreet cheating in the form of turf squares it worked. In summer a sandpit and swing were enjoyed by the children and I tried my hand at barbecuing. In winter we built an enormous snowman with charcoal eyes and a parsnip nose which over the weeks slowly subsided into a muddled heap of snow. It was like living in Scarsdale without the commute.

Caroline had reached the age where she needed a nursery school. I felt a pang at the Cape to find her kneeling at her bedroom window listening to the noise of children in the distance and saying wistfully, “chulna”, her closest approximation to the word. I can’t remember how it happened but we were approached by Miss Everett’s Academy to ask if she would like to attend. It was close by and we would, but cost was a problem. The school waved this away. As a nursery school for baby Rockefellers and other well-established New Yorkers they were looking for a little diversity and it appeared that Caroline met the need. It did, because when the New York Herald-Tribune ran a piece on the academy entitled ‘Where the Junior Jet Set Play’ it featured a photograph of Caroline pointing vaguely to New Zealand on a globe.

Walking her there across Park Avenue became a morning routine. On one occasion, just outside our front door on 78thStreet a large dog on the other side of the road snapped his leash and dashed at Caroline, pursued by his shouting owners who could see bites and lawsuits taking shape. The dog, however, screeched to a stop just in front of her and sat down. Caroline reached out a hand to pat him and said, “Don’t be frightened, dog”.

As Thanksgiving loomed and fall faded, I and the rest of the Mission were eating lunch in our accustomed place around the corner from the office when a man appeared in the door, shouted “They just shot the President” and vanished. We looked at one another. It seemed improbable but we pushed aside our plates to find a shop window with a television. After an initial confusion – shots had been fired at the President’s car from behind a grassy knoll, he had been injured, he was in intensive care – it became clear: the President was dead. The reality came fully home as I stood in my office again looking up Third Avenue, watching the row of flags jerkily coming down to half-mast.

It was an experience never repeated in my life. The whole country was in shock; the death of the President seemed more like the loss of a family member than the head of state. People in the street walked along with reddened eyes. That night, unable to sleep, I listened to the radio station WQXR and the announcer began to cry when naming the next record. People felt bewildered and helpless, feelings increased when the assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, was murdered as he was moved along a corridor – a murder seen live on television by millions including Julie.

The nation was drifting but the anchors held. The main anchor in those first few days was Jackie Kennedy herself. Her gallantry and restraint steadied everyone; you could hardly break down or behave badly when the widow’s conduct was so exemplary. The rituals of a state funeral were themselves steadying, along with memorable human moments: Cardinal Cushing at the graveside, his cracked voice interrupting the Latin to say “Dear Jack”; General de Gaulle towering above everyone else and reverently removing and replacing his kepi when everyone else was doing the opposite.

My last memory of the President was only ten days earlier. I was having my hair cut in a barber’s shop on Second Avenue when there was the noise of an approaching cavalcade. The barber said it was the President but declined to interrupt proceedings. I got out of the chair and stood in the doorway, still with the barber’s cloth draped round me, to see the President go by. He was sitting in an open convertible with his arm along the seat, talking and laughing in the sunshine. I remarked to Julie that night on the danger of sniper fire in driving past lines of four-storey houses on a street like Second Avenue. What I saw was the last time when the head of the American democracy could move freely. The days of waving to passing boats or joking in the back of a convertible had gone forever and elected leaders became increasingly secluded like Chinese emperors. It is a melancholy sight when a line of black cars goes by at speed in one of which the President is sitting out of sight.

Even Christmas, normally a cheering time in New York, was overshadowed by the feeling of loss, though the snow still fell softly, the red-robed Santas rang their bells on street corners and people bustled in and out of the brightly-lit shops. We now had a three-year-old and a toddler; it was time to do a proper Christmas. We walked in the snow to get a sweet-smelling spruce and a gold star to go on top of it and set it up in a corner of the living-room. When it was decorated we lit a blazing wood fire and drank hot buttered rum. Two days later it was Caroline’s birthday and we had a small party and a birthday cake with three rather lonely candles.

As part of our modest Christmas festivities we invited the family of a colleague to lunch. It was an unhappy occasion dominated by a pushy mother who spent much of the time shouting at her pretty sixteen-year-old eldest daughter who seemed on the brink of a breakdown. Julie saw a gesture that would help and took the girl downstairs to try on the pink “going-away” dress from our wedding day. It fitted perfectly and Julie gave it to her. In the late afternoon the family straggled out of our door in silence, like a defeated army, but the daughter still in the dress had a new gleam in her eye.

The following spring my time at the Mission was suddenly foreshortened by the need to fill the position of head of the South Pacific and Antarctic Division in Wellington. The inconveniences of an earlier departure date were minor except that I had not taken delivery of the right-hand-drive car I had ordered for New Zealand. Bringing home a car duty-free was one of the few perks of the foreign service. There was a seller’s market for American cars and some were said to have paid the deposit on a house with the profit from selling their car. I had no such plans but Customs rules were that the car had to accompany the returning officer home within a limited time. The only available ship that fitted my need would sail from Elizabeth, New Jersey in two days’ time.

I flew to the American Motors factory in Kenosha, Wisconsin, where the car, a dark red Rambler specially built to accommodate right-hand steering, had just come off the assembly line. Getting it to New Jersey to meet the ship would require twenty-four hours of continuous driving. The technicians that gathered round the car were doubtful that this would be possible, but in a sporting gesture they filled the car with their own petrol and gave it an encouraging smack on the boot as I drove off.

It was the longest continuous drive I have ever made, and rather monotonous given the excellent engineering of the American highway system. As the hours went by and I rolled through six successive states my main aim was to stay awake and the main interest for passers-by, toll-gatherers and petrol stations was that I seemed to be driving the car from the passenger seat. When cars passed heads would suddenly swing round as someone said, “There’s no-one driving that car”. At tollbooths it was no longer possible to toss the necessary quarters easily into the baskets as you drove through, and stopping for coffee or petrol always brought a small crowd of people who found it difficult to believe what they were seeing.

I drove through the night and some states like Indiana and Ohio appeared only as clusters of lights marking towns. In the middle of the next morning, more or less on schedule, I rolled on to the wharf at Elizabeth to see my ship out in the stream, hooting mournfully. It looked as if I had lost my gamble by only a couple of hours. Then a less sleepy examination revealed that the ship was coming in, not leaving. The relief was great and once the car was loaded I took the bus back to Manhattan, asleep for most of the journey.

After the hurly-burly of farewell parties and dinners we planned on our way home to recuperate for a few days in Papeete. The extended airport had not yet been built and there was little tourism. When we engaged our chambermaid to babysit while Julie and I had dinner she refused any payment. When I insisted, placing the roll of Pacific francs in her uniform pocket, the following day it quietly turned up again on the table as we left, an attitude that was unlikely to survive more tourists. Because of French nuclear testing the streets were full of French Legionnaires. Caroline had the distinction of being thrown out of Quinn’s Bar for being under age (she was three). Gerald, running with a bottle of cola in his hands, fell and split his upper lip. It was repaired by a Foreign Legion surgeon with a Gauloise cigarette hanging permanently from the side of his mouth. Then we were home, to start married life for the first time not in foreign surroundings but in Wadestown.

[4] Lance told me this himself.