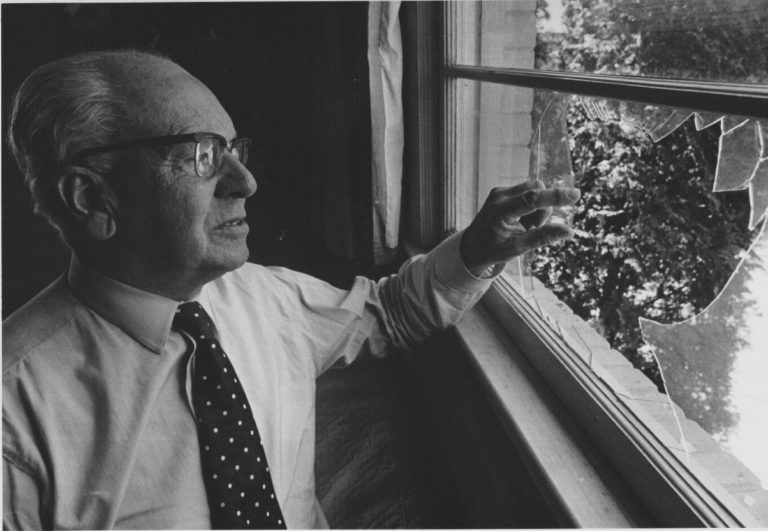

Eulogy – Simon Murdoch, CNZM

It’s an honour and a privilege to have been asked by the family to speak today about Gerald`s working life. I do so with the hope that my words may capture , not just Gerald`s professional career, but something of the impact he had on those who knew him through work, and remember him today with respect and affection.

His career falls into 3 parts- a diplomat for over 20 years , the majority spent in NZ`s overseas posts; a senior public servant, Wellington- based, with leadership of two significant agencies of state; and in retirement, a public intellectual and commentator on international affairs, security and defence.

My path did not cross Gerald`s until January 1980 when he was High Commissioner in Singapore, though of course, I knew of him by reputation. To tell his story before then I have had great help from his MFA peers and colleagues- Richard Nottage, Judy Trotter and Neil Walter in particular. But more so from Gerald himself, from his three fine books, especially his memoir Final Approaches.

For the period after 1980, others who worked for him and with him in PMD, DESS or MOD have provided insights. Two Ministers from that era- Sir Don McKinnon and Hon Max Bradford – have added unique perspectives. I thank all of you; what follows is a blend- a mosaic of Gerald’s times and ours with him. But it is what he was to us as a boss, a colleague, a valued adviser that I want to illuminate. In doing so I will also touch upon Juliet who completed the Gerald we knew in so many ways, and, as he said, without whom, none of his career would have been worth it.

The diplomat

Gerald might qualify for that familiar epithet, the “born diplomat ‘ but whatever his innate skills, he was made into the outstanding diplomat he became by wise mentoring reinforced with rich learning and growing experiences. His mentors were the founding fathers of MFA, particularly Frank Corner, determined to build a foreign service with a sharp edge- diplomats whose skills would hold up to the competition in any hall of power.

Gerald joined the fledgling department in 1958 ; they were very glad to have a recruit of his academic brilliance, and quickly gave him responsibility for key matters relating to the post-war South Pacific upon specifically decolonization, the bringing- about of independence in Western Samoa To. Apia he went within a year. That was where he and Juliet married.

When the ending of our Trusteeship moved to its UN phases, Gerald went with it- cross-posted to New York. There he was able to take in the edgier drama of the decolonization process beyond the Pacific, and to feel the tensions of the Cold War close up, as the Cuba Missile crisis burst on America.

As Gerald tells it, this was a time of growth. He is both excited by the experiences, and by the sense that he has found a profession that absorbs him. As he practices it in Apia and at the UN, he is getting better at it- the contact-making; the listening; the reading-the-room; above all, the sense-making. He reports coherently on all of this- the “whats really going on”, and what it means for NZ.

His becoming phase next took a significant turn. Gerald had been selected by McIntosh to join the staff of the new Commonwealth Secretary-General – the Canadian diplomat , Arnold Smith.

This was a plunge into high-level global political and security affairs ; the post -colonial order in Asia and Africa was fraught; and it was no ring-side seat for Gerald. At Smith`s side for almost 4 years, through the Rhodesian UDI, and Biafra/Nigeria, and amidst both the summitry and the behind_the-scenes negotiations, he was exposed to crisis diplomacy. And to its limits when faced with raw power and force of arms. I feel it shaped his world-view profoundly and is the root of the decidedly realpolitik views he held about international relations and national security.

In 1969 , the Ministry cross-posted Gerald yet again- from London to Washington, where he was responsible for the political team at the Embassy, as well as having accreditation to the intelligence analysis ( not operations) arm of the CIA and its State Dept equivalent (INR). Gerald and his team had their daily beat , to cover the vastness of State Dept and the National Security Council, then the fortress of Henry Kissinger. The core of it was cultivating contacts and gaining access to the points where policies that could affect NZ were being shaped. The Holyoake government had equities in the Nixon Doctrine- what happened next in Vietnam and how China-US relations could change. Gerald called this chapter “A Washington Spectator”, but from what he told me when the same job came my way, it was very much a growth experience- exposure to the way big powers form strategic policy and how critical analysis is to informed decision-making. In the field of politico-military affairs- a Washington specialization- Gerald found a framework for his own thinking and made contacts of enduring value.

Not long after the 1975 election Gerald was nominated to be High Commissioner in Singapore. It was approved by the new Government under Robert Muldoon. Over the next three years, Muldoon visited Singapore several times; there he found Gerald had formed a bond with its charismatic nation builder, Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew.

Gerald, by this point, was the finished product: a seasoned and versatile diplomat. He had seen close up how big powers and big power international politics worked; he had grasped the tradecraft of multilateral negotiation; he understood the South Pacific and rising Asia; he was known in the capitals of NZ`s closest partners. He had been a close adviser to Ministers and Prime Ministers. He had well-practised diplomatic competencies, and a formidable intellectual grasp of the ebb and flow of world affairs- his framework was the core of a sound professional judgement. He lacked nothing in interpersonal skills. He met people easily. With Juliet`s immeasurable support, he made -and kept- as personal relationships- important international contacts with influential people.

He was esteemed by his bosses at MFA, and liked and respected both by his peers and the junior staff who he, in his turn, mentored with tolerance and kindliness.

The senior public servant

The Prime Ministers’ Office had undergone a transformation after the Kirk years. On both sides of politics it had been recognized that as Chair of Cabinet a modern PM needed more than secretarial and administrative services; policy-analysis capability, and professional advisory support were essential. The task of bringing this change into being had fallen to Bernie Galvin of the Treasury. At the centre of the new machinery was a7- 10 person “Advisory Group” whose charter was to keep the PM fully abreast of emerging policy issues across the bureaucracy covering all sectors of the economy; and social matters. Members came from public and private sector positions on two year terms. It was located in the Beehive one floor below the PM`s office and political/media support team. I went into the MFAT “slot” in the Group in October 1979.

By 1979 , after five years, Galvin had given his all and wanted to return to Treasury. He had visited Singapore that year and, with Muldoon`s blessing, put to Gerald that he was his preferred successor. Early in 1980 the Hensleys left Singapore, and Gerald arrived at the Beehive to understudy Galvin for several months until taking over from him in September.

Gerald, on arrival, immediately got to know the Group, and when not otherwise engaged with Bernard and the PM, joined in its processes, activities and practices which included preparing “the boss” for Cabinet Committee meetings and for Cabinet itself, besides “trouble-shooting” on problematic matters where the PM had indicated he wanted to be hands-on. The major domestic issues- the effects of the oil shock; the “Think Big” energy projects, and the support of the primary sector all generated policy disputes,

For me , it was a relief to have in easy reach, someone with Gerald`s knowledge and authority as a guide; Muldoon was suspicious of MFA, and often questioned its advice. He was, both as Treasurer and PM, very engaged in international matters, travelling frequently. Our trade access future in Europe deeply concerned him; he was facing a rising tide of pressure about sports contact with South Africa, and there was trouble over ANZUS and port access for allied warships. Gerald let me get on with the job, but was always available to step in when the going got rugged and the PM testy.

Gerald and I went through the 1981 Springbok Tour together- the failed final efforts to persuade the PM not to go ahead; the protest/ Police clashes, the fraying of communities, and the international opprobrium. That is when I saw Gerald`s steadiness of temperament and cool judgement at its best- with a tired, distracted, less than well but still combative- Prime Minister.

Gerald has written memorably about this period, which culminated the post-election devaluation crisis of June 1984. Our paths did cross once when, that February he accompanied Sir Robert on what was to be his final visit to the US, and he told me there how depleted Muldoon had become and how difficult the ANZUS issue was becoming.

The new Prime Minister told Gerald he should continue as Head of PMD ‘for the time being’. That time stretched into 1986, and covered a far-reaching and wrenching domestic economic reform programme , and two foreign policy matters of similar impact- the unfolding of the ANZUS dispute and the Rainbow Warrior sabotage. Much has already been said and written about David Lange, but Gerald was in an unique position with the PM through all three issues, and his views- sympathetic but also critical- must carry weight accordingly. Gerald found him elusive, and hard to read on matters of decision, especially where a PM would normally be expected to weigh in politically with his Ministers and Caucus. He chafed against being enclosed by advice.

It was perhaps inevitable – always just a matter of time- before this PM wanted a change. By the time I returned to Wellington in 1987 Gerald`s role had been disestablished, and his new title-Coordinator for Domestic and External Security- gave him a distant office- in an ancient prefab behind Parliament Buildings.

It must have been an awful time personally for Gerald and the family but Gerald barely spoke of it to me at that time.

Whatever he may have felt privately, Gerald very professionally set about the task at hand, and events very quickly showed why such a coordination function belonged close to the PM and the Cabinet, rather than in an operational setting such as Civil Defence, or NZDF. The first Fiji coup and the Nadi hijacking; an outsize natural disaster in Cyclone Bola and other big ones. His relationship with David Lange was restored by the creative forces DESS brought to the response to these disasters. When the PM resigned from office in August 1989, Gerald, about to take a break himself- a year as a visiting fellow at Harvard- called on him to say goodbye. It was the correct and courteous thing for a senior public servant to do.

Gerald returned home in 1991 to take up the position of Secretary of Defence, the civilian-led, policy and budgetary side of the NZ defence establishment. In that role he would utilize his strategic mindset, and his grasp of politico-military affairs to advise the Bolger government ; two White Papers were done on his watch. This was that unipolar moment -the end of the Cold war; the reunification of Germany and the demise of the Soviet Union, on one hand and a time of common purpose in East Asia and the Pacific. But also a time to try to restore some elements of military cooperation with allies, especially the US. Gerald put a lot of thought and effort into that.

It was also a decade of some activism for NZDF- firstly in the deployment to former Yugoslavia and, closer to home, the Bougainville peacemaking process. Gerald contributed to the high -level advice on all such matters; I saw at first hand his relationship management skills with the Chiefs of Staff. With Bougainville , much of the critical diplomacy was led on the ground by John Hayes, the High Commissioner. John had first come under Gerald`s wing as a junior officer in Singapore; he says simply “Anything I learnt about diplomacy, I learnt from him”.

This rising tempo of NZDF operational activity , especially pressures began to arise in East Timor, revealed a need to think hard about the equipping of the forces, and how to fund acquisitions of big ships and aircraft fit for modern warfare and peacekeeping purposes. Tough arguments with Treasury were the order of the day. Andrew Wierzbicki told me that he never saw Gerald loose his cool or raise his voice. “I only wish I had joined MOD earlier to benefit from his leadership “.

Gerald had three Ministers of Defence in that time. The last, Max Bradford told me that Gerald had the most extensive personal links with key overseas defence partners, and this contributed to NZ`s ability to punch above its weight internationally ; he valued the Kiwi ability to rise to a crisis with that no.8 fencing wire pragmatism. Gerald`s focus on key NZDF capability , for the world as it was, not how it should be, was laser-like.. “

When Gerald retired in 1999 after 8 years as SecDef, he was awarded CNZM for his 40 plus years of exemplary public service. Neil Walter said Gerald epitomized all the qualities, professional and personal, looked for in a NZ diplomat, and was instrumental in determining NZ`s response to many of the most difficult and most important foreign and defence challenges we faced as a small nation.

We remained in touch when he came to town, and I was able to visit him in Martinborough where, as ever, he was a help and a comfort. It was always pure pleasure to be with so thoughtful, astute and companionable a man. I was never other than strengthened and supported by Gerald. For that I will always be grateful.

And now, as I and many others try to make sense of the murky world of today, my inner voices will be prompting yet again that question- what would Gerald make of it?

I will miss him greatly. Hail and farewell.