Fiji Coup – Escape from Suva

Our intelligence got off to a shaky start on Fiji, giving the Government an assessment that the newly-elected government of Dr Bavadra in April 1987 was unlikely to last its full term. This proved a considerable understatement because it was overthrown a few weeks later. Next time, our intelligence machine was quicker off the mark. I got a message just after ten in the morning on 14 May that something strange was happening at the Parliament Building in Suva, told Prime Minister David Lange and he announced it to the world, beating even CNN.

A few days after, there was another unpleasant message: an Air New Zealand jumbo coming from Tokyo had been hijacked while refuelling at Nadi. In this sort of incident you start in a fog of ignorance, not knowing who the hijackers are, how many of them, what support they have and what they want. The next two hours were spent by me in a continuous series of telephone calls from the Prime Minister’s office, helped by Police Minister Dame Ann Hercus who came by and nobly offered to answer the other phone. We gradually established that there was a single hijacker, an Indian Fijian, with no known support other than a brother who had hung mournfully round the airport, that he had several sticks of dynamite strapped to his waist, and that he wanted to be taken (as they all did those days) to Libya.

We had two pieces of luck. Air New Zealand could communicate with the pilot reasonably discreetly through a single sideband radio in the cockpit, and a very competent Fiji Inspector of Police took over the control tower and offered helpful advice as we opened discussions with the hijacker. Our initial aim was if possible to prevent the plane from taking off because once it was in the air with a full load of fuel it could end up anywhere, but we told the pilot that he would have to make the final judgment since it was his life that was at risk.

As it became gradually became clear that we were dealing with a single hijacker, we settled down to negotiation, getting him first to shift his ground and demand to fly to Auckland. At this point I made a mistake that could have been disastrous. The inspector said they had located the hijackers aged parents and had them in the control tower. Would it help to put them on the radio to speak to their son? This seemed an excellent idea and I said, Put them on.

Unfortunately his mother, instead of soothing words, wept and berated him saying, “Son, you have brought disgrace on the family which time can never erase. We can never hold up our heads again, and so on..” The pilot came on the line in a vehement whisper: “For God’s sake get her off”. The hijacker was becoming highly agitated and fumbling with his dynamite belt. So Mum was unceremoniously yanked off the air and the negotiations resumed.

The incident was finally resolved by the nuggety flight engineer who seized an opportunity to knock the hijacker out with a large bottle of Teachers whisky. By then I was already en route to Nadi on the Prime Minister’s instruction. I arrived to find the maker of defiant demands motionless on a stretcher and the bottle of Teachers borrowed by the police as Exhibit A. When it was returned months later it was still corked but had mysteriously become empty.

The Prime Minister then asked me to go to Suva to help out our hard-pressed embassy so I rented a little car and drove across the island. I was listening to (of all things) the Goon Show when we reached what seemed to be a traffic jam on the outskirts of Suva. Suddenly an agitated gentleman leant into the car and said “Sir, I must ask you to turn back at once, you must turn back at once.” I was reflecting on this strange message when the front and back windscreens of the car in front of me simultaneously dissolved into fragments. I realised that I had driven into a major riot. It was possible to turn the car and bump over some waste land to take a back way to the High Commissioner’s house on the ridge above Laucala Bay.

Looking forward to some lunch I arrived to find another crisis: fifteen minutes earlier the deposed Fijian Prime Minister, his wife and private secretary had taken refuge in the house. Some coffee was hastily made and I sat down with Dr Bavadra to talk things through. A kindly simple country doctor, he seemed dazed by the turn of events. His wife, Adi Kuini, was composed and resolute.

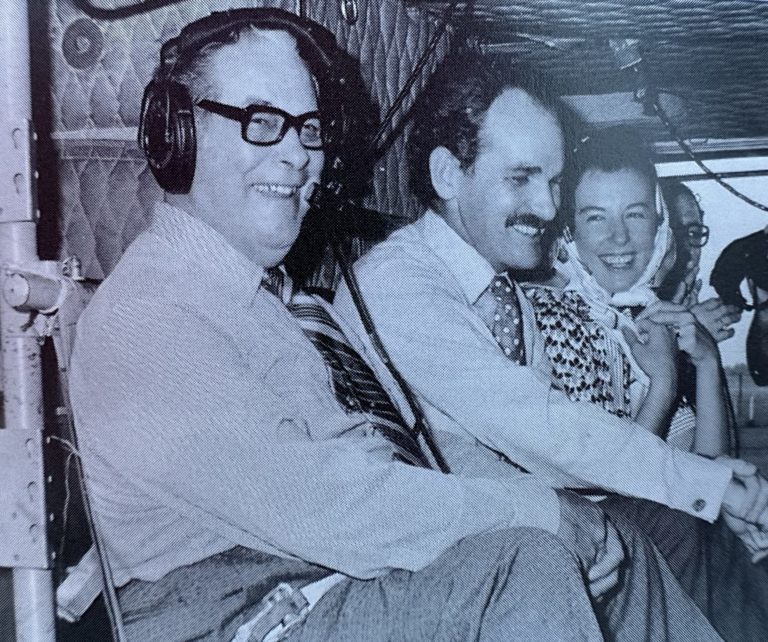

News came that a large mob was moving along Laucala Bay’s main avenue in the direction of the house. It was possible that they knew the Prime Minister was there. There were some sailors from HMNZS Wellington guarding the house but they would not be able to hold back a crowd. An evacuation plan was hastily worked out whereby the little Wasp helicopter from Wellington would pick up Dr Bavadra and his wife and the rest of us would scramble down the hill and find our way to the ship as best we could.

The private secretary was not too happy with this plan but the helicopter was simply too small for more than two passengers and was unlikely to have the time to make a second trip. After preventing the enthusiastic sailors from chopping down half the trees in the garden in order to make an unnecessarily large landing pad for the helicopter, we settled down to await events. Half a mile from the house the mob was checked and dispersed by the army and the tension eased. Dr Bavadra and his party later left the house and made their way safely to the Western Division where he had his political base.

Over the next two days there was still sporadic rioting but the army gradually imposed some semblance of order. It became possible to plan a final and delicate task. Dr William Sutherland, a senior adviser of Dr Bavadra’s, had been obliged to go into hiding in a taro patch when the coup occurred and had later taken refuge with his wife and children in our High Commission in downtown Suva. I was asked to help him get safely out of the country.

I still had my little car and the plan was simple enough. The High Commission building was just across the road from the central police station, now occupied by the army. But we decided that the sailors on guard at the front door would simulate a fight when they were being relieved and, while the Fijian army looked on fascinated at this breach of discipline by New Zealand servicemen, we could quietly drive away through the back. I walked over the ground in the evening and it seemed negotiable for my car – a large green lawn belonging to a convent at the back.

At six o’clock the next morning the sailors duly staged their fight and we sneaked away. Unfortunately, overnight the nuns had done their washing and what had been lawn the day before was now filled with enormous quantities of sheets, habits and what have you. I bumped along blindly, frantically brushing sheets aside while waving jauntily to two understandably startled nuns and calling out ‘Lovely morning’ through mouthfuls of clean linen.

I heaved a sigh of relief when we finally emerged on to a leafy and quiet side street, then checked the rear-vision mirror and froze. Behind us was an army truck with a six-man patrol in the back. I burbled away to my passengers who were perhaps already losing what little confidence they had in their Pimpernel, and took the next turning to the left. So did the truck. I turned right, so did the truck. In her anxiety that I might betray them, Helen Sutherland said to me sharply, “This is not the way to the main road”. I pleaded ignorance of Suva’s streets, took two more turnings and then found that the truck had disappeared.

Time for another sign of relief, quieter now because my passengers didn’t know the army truck had ever been there. But then another chilling of the blood. I looked at the petrol gauge for the first time and it showed empty. I had visions of an ignominious end: all of us being arrested as we waited by the roadside beside a car which had run out of gas. We drove on, with my burbling becoming more and more abstracted as I tried to calculate how many more miles we might have.

Then relief again – a large petrol sign showing over the palm trees. I drove into the forecourt and pulled up, looking out of the driver’s window at a large pair of brown legs. My eyes travelled slowly up past a navy sulu to the face of a large and benign police constable. The combination of a police and a petrol station is an eccentric one. It’s possible this one on the Nadi road was the only example in the world, but it was the one I had chosen.

“Ah there, Sergeant,” I said jumping out and leaning against the car hoping that my male passenger had the sense to crouch even lower under the luggage on the back seat. His wife and I were ostensibly New Zealanders returning from a holiday. “Tell me, Inspector, how are things” I said handing $20 to the rather nervous Indian petrol attendant who had appeared. He took what seemed an age, fumbling with the cap, overfilling the tank, going back for rags to clean it up, apologising profusely and then going back for change. “Tell me about your lovely family, Superintendent,” I said, suppressing with difficulty the urge to do a jig of impatience, until at last everything was done. “Nice to have met you, Commissioner” I said driving away with exaggerated calm.

After that, it was relatively plain sailing. I dealt with the military checkpoint on the Sigatoka bridge by playing the idiot tourist – a role you will agree came fairly naturally by now – and driving straight through with a cheery wave. There were shouts from the soldiers but no shots followed. I put my charges into a motel near Nadi Airport, bought them a large lunch and went off to arrange things at the airport.

I had luckily made an airline contact during my earlier stay whom I felt I could trust. Outlining the situation, I asked for his help in getting them on the Sydney flight. He delivered splendidly and we arranged that the passengers would arrive just as the flight was closing and after all the others had gone through. That way they could go straight on to the plane with the minimum risk of being spotted. (Although I learnt later that they had been recognised walking across the tarmac.) We followed all this to the letter, I saw them through the gate, and retired to the main concourse in case there was trouble. The book I had chosen to read while waiting was less than suitable – ‘Life among the Cannibals, or Two Years in Feejee, by a Lady’. While pretending to be absorbed, I became aware of a young man standing before me. He said, “Mr — (my contact) has asked me to tell you that the Sydney flight has left and that there were no empty seats.” From this oblique message I knew that my charges were safely away. I gave another sigh of relief, and this time it lasted.