Prime Ministers from Below – David Lange

David Lange was good at politics but was not a politician. That is to say, he had a quick appreciation of people and a quick intelligence to go with it, but he was not deeply interested in power, had never undergone the unflagging effort required to gain and wield it and was often uncertain what to do with it when he had it. We once fell to talking about what career we might have chosen in other circumstances. Coming from a legal family, I supposed I would have been a lawyer. David Lange thought he would have ended up as General Manager of something like the Metropolitan Insurance Company, a notably unenterprising ambition for someone of his intelligence. It seemed to be a sign of his diffidence that, though he had great fluency and a very good law degree, he stayed away from the higher courts, remaining a police court lawyer able, as he said, to work out his defence while walking into court. By nature, he was a defendant not a prosecutor.

He was perhaps unique among Prime Ministers in that he had great intelligence but little willpower. As his colleagues, Mike Moore and Dick Prebble said, “We carried him to the Prime Minister’s chair. We saw that he could win and put the rest of us in power.” It was a good call. He was a superb campaigner, with a natural speed of response, a quick wit and abundance of human warmth and charm. Although he probably did not yet realise it, he was a born entertainer.

He was not so well suited to being Prime Minister. He was wearied by the daily grind of government and the relentless concentration needed to keep it working. The Labour Party, a party of ideals and therefore differences, required a strong hand but Lange was temperamentally incapable of providing such a hand. He complained to me every time he had to attend meetings of the Labour Party Executive Council and left them as soon as he could, often part-way through on the pretext of having a press conference, something no previous leader would have done.

Nor did he especially like his colleagues. He liked to tell irritable but funny stories about almost all of them. Roger Douglas was a notable exception to this in his first term but in the second the comments about him were not funny but bitter. His methods of dealing with his less formidable colleagues could be peculiar. One afternoon when I went to see him, I was intercepted by his Private Secretary who silently pointed to Frank O’Flynn, Minister for Defence, patiently sitting outside the PM’s door, and then led me round the Beehive’s circular corridor to the dining room where the PM had temporarily shifted his office, poor Frank having been told that he was out.

Politicians are good judges of character – they have to be – so I assume his Cabinet were all aware of his weaknesses but these mattered less as long as he held the electorate in his hand. The Left group, campaigning for a revolution in foreign policy, certainly had no illusions and kept a sharp eye on him. Others, like Mike Moore, enjoyed being left alone to get on with their portfolios. Prebble said that he carried Cabinet meetings along in a wave of jokes. Half the business on the agenda was over before everyone had stopped laughing. He showed few signs of having any policies of his own but was happy to roll along with the proposals of Douglas and Prebble until the strain of his second term led him to rebel.

He was not one to push an idea through the system unless someone else, often Palmer, was willing to help him. In a conversation once we talked about the need for another look at our social welfare system. He suggested a Royal Commission might be useful and I agreed, provided that the terms of reference were precise enough to prevent a commission wandering over all New Zealand’s ills and the right people were found to direct it. I suggested a possible director and Lange said he would think about a chairman. He rang me back to suggest Ted Thomas which I thought an excellent choice. Then the left-wing in his Caucus heard of it and began suggesting suitable women for the commission. Lange lost interest and the idea had to be resurrected by Palmer, but it ended with an enormous door-stop report rather than a few recommendations that were doable.

When he was uncomfortable he became murky and furtive. At a time when he was under pressure to get rid of me as head of his department he talked to me at some length one afternoon. The uneasy jokes rolled by and the clauses billowed but the meaning remained unclear to me. It was only when I was eating dinner at home that night that I realised he was offering me the post of ambassador to the UN. I immediately rang him and said no; he did not seem bothered.

We worked comfortably enough together, or so I thought, but he was under constant pressure to make a change from one who had also advised (or more accurately tried to advise) the hated Muldoon. The only answer in the end was to abolish the Prime Minister’s Department, of which my title was rather pointedly Permanent Head. So New Zealand became the first and so far only Commonwealth government to shelve this support for a Prime Minister, if only briefly. The farewell morning-tea in his office, an essential rite of departure especially for Labour Governments, was a grisly affair with Lange’s embarrassment revealed in an unconvincing heartiness and weak jokes about my new role as the Domestic and External Security (DESC) director.

His nature was ambiguous and therefore secretive. This was, with hindsight, a major element in the Buchanan affair. After the election and change of government, Ewan Jamieson, Merv Norrish and I sat down with him to work out how to meet his manifesto pledge. The problem was not the exclusion of nuclear vessels – that was settled by the election – but how to reconcile this with our continuing membership of ANZUS which was also a manifesto pledge. We looked at various possibilities, settling on an early visit by a clearly ‘clean’ warship, and Lange told Jamieson to go to Honolulu and get the commander there to agree to an acceptable visit. He did and Lange’s three advisers felt we had made a big step towards solving the problem.

What we did not know (it seemed inconceivable that a Prime Minister would work closely with his advisers while being silently uncommitted) was that Lange was not keeping faith with us but was riding two horses, or “surfing” in Lee Kuan Yew’s comment to Mrs Thatcher, to see which would turn out to be safer or more attractive. While he told us to reassure the Americans and Australians that he was anxious for a compromise, he was making public speeches that he would never compromise. While we, on his instruction, were busy with a Buchanan visit his anti-warship rhetoric was as fiery as ever. He was saying nothing to keep his Cabinet informed, leaving even his deputy in the dark. Even when Cabinet took the decision to exclude the ship, no-one with the possible exception of Geoffrey Palmer knew what they had decided. Michael Bassett kept notes of Cabinet decisions but when he checked for this occasion there was nothing; he was still writing down the previous decision when the matter was settled. Even then Lange was still furtive, saying untruthfully to me that evening, “You have no idea how difficult it was in Cabinet. I was in a minority of one.”

This same secretiveness and preference for acting as a loner, despite presiding over a Cabinet government, was revealed when an Air New Zealand plane, returning from Tokyo, was hijacked when refuelling in Nadi. That this was the first challenge for the newly-established Director of DESC was fortunate since I had earlier made arrangements (copied from the British) for a Terrorism Committee chaired by the Prime Minister with a varying membership of ministers and officials to deal with unpredictable threats. In a crisis it would work from the basement of the Beehive where all the necessary communications equipment had been installed. We had carried out a full-scale exercise of all this, as it happened for a simulated aircraft hijacking.

So I went confidently to the Beehive to tell the Prime Minister that the lights and kettle were on in the basement for him to move down immediately to take charge. It was a considerable surprise when the anarchic Lange, who could upset any system devised by man, said he would not move. When I said, how will we manage? he simply said, “You’ll manage”. At no time was there any suggestion of calling a Cabinet or even of briefing any of the key ministers.

I retreated to the anteroom where two of the three phones were already ringing. I spent the next two hours sprinting from one phone to the next as my own colleagues, like the Defence Chief and Police Commissioner, tried to discover what was going on. At one point the Minister of Police, Anne Hercus, arrived and asked if she could help. She answered a ringing phone to find herself talking to her Commissioner, and neither of them knew what was going on.

I had to concentrate on talking to Nadi, to find out myself what was going on. There is a dark period at the beginning of any terrorist emergency when you know nothing of who or how many are behind it, how well organised they are and what they want. Fortunately I could talk to the pilot through a loudspeaker heard by everyone in the cockpit, including the hijacker, and a radio beside his seat through which we could talk more privately. There was a competent Fiji police inspector in the control tower who could talk also speak to us and the cockpit. Out of the hour-long confusion encouraging facts emerged. There was only one hijacker who was protesting against the recent coup in Fiji, he was talked out of flying to Libya (which the fully refuelled plane could have done) and the pilot managed to get him to demand to be taken to Auckland where the plane was going anyway.

Then I made a misjudgement which could have been fatal. Inspector Govind Raja came on the line to say that he had the hijacker’s parents with him in the control tower. Should he put them on? It seemed a good idea and I agreed. A distraught mother then came on, saying things like “Son, you have brought shame on us which can never be erased” and starting to elaborate at some length. The hijacker became nervous and began to fiddle with the explosives around his waist. “Get her off”, the pilot hissed on his radio and Mum and Dad were abruptly ejected.

After that the hijack began to come under control. The hijacker had no backup, he had begun to shift his demands and it looked as if the key to a resolution was to keep talking until he either gave in or fell asleep. I ducked back into the PM’s room to report that we were making progress. He then produced his second surprise of the morning saying, “I want you to go to Nadi”. I protested saying the situation was in good hands with Air New Zealand staff and Inspector Raja and there was nothing I could do there. We argued this for some minutes but when he repeated his order for the third time I had to agree. As I turned to leave the room Lange resumed his discussion with John Henderson, the head of his office, and Tim Francis, deputy secretary of Foreign Affairs, and I caught a reference to NZ troops being sent to Nadi. The effect of troops landing in the course of negotiations with a nervous hijacker might literally blow everything up. I asked for the PM’s assurance on this and he gave it at once.

When I arrived in Nadi the hijacker had been knocked out by the resourceful flight engineer and Amjad Ali was being wheeled away unconscious. I did, however, note the presence around the airport and perimeter of a battalion of experienced Fijian soldiers and was relieved that I had sought that assurance. But at that stage I knew nothing of the extraordinary request made of the Defence Force while I was in the air.

Just after I had left, the Chief of Defence Force had come to the Beehive to find out what was happening. He had been told to send an aircraft with counter-terrorist to Nadi as soon as possible. He found a number of people milling around in Lange’s office and asked that the instruction be put in writing. Lange dictated a directive for an aircraft to be despatched with sufficient troops “to act as required to protect New Zealand’s interests in Fiji”. Neither the PM or anyone else was willing to elaborate on this vague instruction.

In Auckland Robin Klitscher, the air commander, was surprised when an agitated Brigadier, Michael Dudman, walked into his office wearing field kit and a side arm. He had been instructed to take fifty troops to Nadi. When he asked about arms, he was told by someone in Lange’s office to take them but not show them on arrival. There was no instruction on what these troops were to do or indeed why they were even going. As an experienced officer he was well aware of the implications of an uninvited military detachment entering a country when armed but pretending not to be. As it happened there was an untasked Hercules already waiting on the tarmac. They discussed whether Klitscher should report the aircraft as unserviceable but this drastic action was made unnecessary by another round of events in Wellington.[1]

A senior air force officer, Pat Neville, remembered an obscure provision in the Defence Act which specified that the Defence Council chaired by the Minister of Defence had to give its assent to any overseas deployment. Lunchtime was spent in an effort to round up the Council members but before this was done Amjad Ali was knocked out and, whatever the purpose of the deployment, its cover was gone. Lange did not forget though. When the Defence Act was reworked the Defence Council disappeared, the victim of the only useful act of its existence.

The mystery remains. Neither Lange nor the two officials conferring with him are now alive and none of them has said or written anything to cast any light on these strange events. Henderson has rebutted the view that the troops were intended to overthrow the coup but neither he nor anyone else has said what the troops were to do. Lange later spoke vaguely of protecting the High Commissioner and the New Zealand community, but they were mainly in Suva and it is hard to see how a landing in Nadi would have been of any use to them.

His intentions about Fiji still defy speculation but he could be more direct in other crises where he showed the straightforwardness and willingness to act quickly which made him much easier to work with. When the Greenpeace vessel, Rainbow Warrior, was sunk in Auckland harbour he still preferred to work on his own but his direction could not be faulted until, characteristically, an over-enthusiastic commitment at a press conference became an embarrassment.

Our arrangements for handling any terrorist incidents had been restructured to provide for a Terrorism Committee chaired by the Prime Minister and supported by an Officials Committee chaired by me. When the sinking occurred we lost twenty-four hours before standing up these arrangements, only realising from the professional placing of the bombs – one to alarm and the other to skew the boats frame so that it could never sail again – that we were dealing with state-sponsored experts.

Even then Lange did not convene the Ministerial committee or brief his own colleagues, preferring to drop in on my committee which met more informally in my office. This unusual procedure meant that he could come and go as he pleased and was not tied down by a more formal structure. It worked well. He was fully up-to-date as the surprising truth unfolded and at a difficult point made the decision that opened the way for a serious discussion.

Though we were gradually piecing the story together the French Government was still unforthcoming, assuming we were bluffing about how much we knew. They clearly did not understand how conspicuous a carload of foreigners travelling through Northland was. The locals seemed to have assumed they were drug smugglers but we had a list of pretty much everything they did on their journey to Auckland. They bought a puncture outfit for their inflatable, they stopped for lunch in Whangarei and flirted with the waitress, they stopped for a pee in the Kaiwaka forest and they even stayed at a motel part-owned by David Lange.

Our very competent ambassador in Paris, John Macarthur, suggested we break the deadlock by sending them the whole folder of sightings. We talked this over on a Friday night. The lawyers were opposed to such a bold step, concerned (in a way that I never quite understood) that this might weaken any future claims against the French, but Lange briskly overrode this and decided that the fat folder should be bundled up and sent. There was a pause and then the Quai d’Orsay suggested that we talk.

After that diplomacy could take over and talks about reparations could begin. The discussions in New York guided by an able international lawyer, Chris Beeby, centred on the amount of compensation New Zealand should receive and whether the two imprisoned French agents could serve their sentence on a French territory. These two, the only members of the team in our hands, were not the bombers but the sweepers, tidying up after the operation was over. Nevertheless they received a severe prison sentence of ten years from the Chief Justice and Lange declared in press conferences that “there would be no sordid haggling or selling of prisoners”. Then the French struck at our trade. New Zealand lambs’ tongues and other imports could not get through Customs. Wellington backed down, the prisoners were transferred to Hao atoll in French Polynesia and were soon back home. Lange was humiliated, a humiliation he took out, not on his nationalistic rhetoric but on the skilful support Beeby had given him.

He showed to better advantage in a domestic crisis. My employment in the Prime Minister’s Department had been replaced by a position as Coordinator of Domestic and External Security. This new office was based on the dubious theory that these different issues were best handled together and that in any case we spent more time and money on external threats when earthquakes and eruptions were a more likely worry for New Zealand.

The theory may have been dubious but the first crisis for the new system was indeed domestic. The ink was hardly dry of the plan of operations we had prepared when Cyclone Bola destroyed a large part of Gisborne’s rural economy. Grapes and tomatoes ready for picking were buried in silt, roads and farmland were washed away and one river rose sixteen feet. Quick action was needed for morale as much as economic recovery and this saw Lange at his best. Although the new DESC system had its plans ready his human sympathy and speed in grasping the problems got us moving faster than governments usually do.

Lange would happily give me authority to make spending commitments in the course of a weekend phone call and make them good with Cabinet the following Monday. When I warned him that it had to be accepted that moving fast raised the risk of mistakes and fraudulent recipients which the press would seize on he simply nodded and said ‘Go ahead’. On a Sunday morning I caught him leaving for church and explained that we needed an emergency work force to dig out the silt from houses and crops. Before his first hymn was over we had announced the creation of the Disaster Recovery Emergency Service. I found a tough former Works employee as foreman who hired an even tougher crew as diggers, the crops began to be recovered and, an unexpected consequence, the crime rate in Gisborne went down.

This overriding of fiscal procedures displeased Treasury and could only be justified by the need for speed. By good fortune it was a young Treasury officer on my committee who devised the novel scheme for land compensation which worked so well that everyone who qualified (and possibly a few that didn’t) had their money within six weeks. This speed meant that my private indicator, the risk of suicides among growers and farmers who had seen their livelihood swept away, showed nil at the end.

However doubtful I thought the theory, the DESC system dealt with only one external event, the coup in Fiji, and a string of domestic problems in its first two years. It worked well because I enjoyed the same immediate access to the PM I had when head of his department and because Lange was always ready to take decisions. We went on to build a wall along the Grey river to protect Greymouth from flooding and then rebuilt the country’s rural fire system to provide a better response for the same money. A review of the border system which recommended a single Border Force in place of Customs and Agriculture was buried by departmental lobbying and then Lange’s resignation left us both without a job.

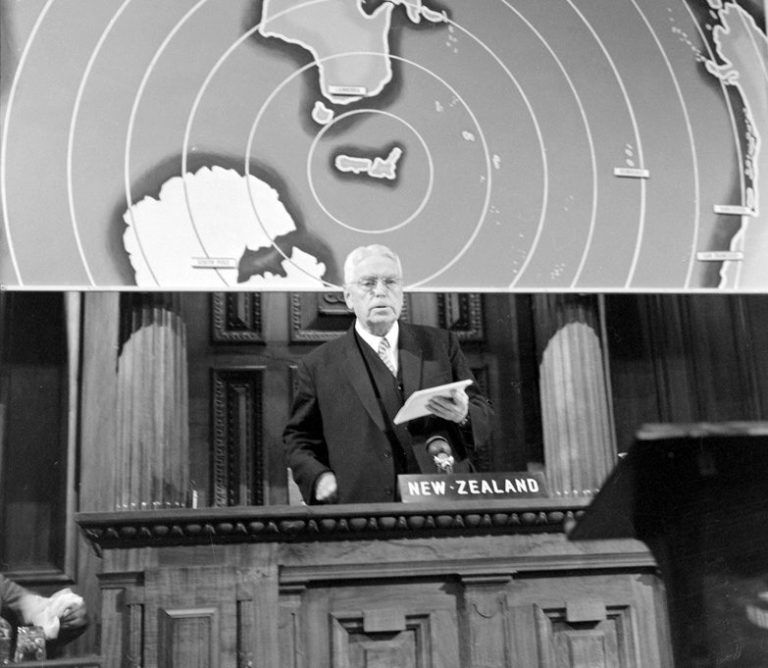

For most of his time in office he was Foreign Minister. In any case the main decisions in that portfolio are always taken by the Prime Minister, as his newly-appointed Foreign Minister found out when he assured the American ambassador that there was no intention to withdraw from ANZUS, only to find the next morning that Lange had proclaimed exactly that at Yale.[2] But given his lack of self-confidence and desire to appease whoever he was talking to, being Foreign Minister in the biggest diplomatic quarrel of our history was not a role he was ever particularly comfortable with.

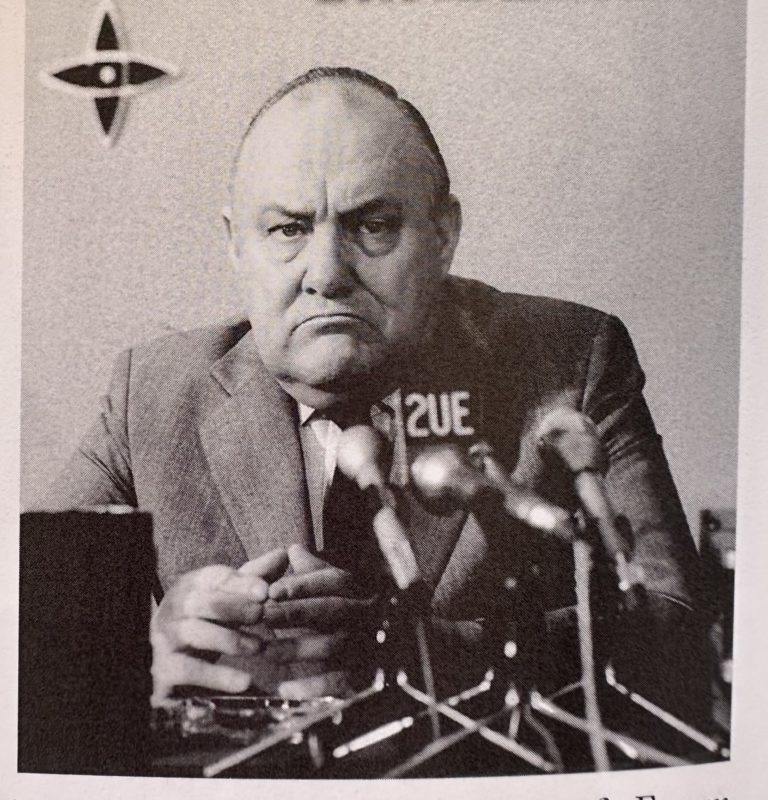

For him the most enjoyable part was the press conferences he gave after meetings, and the nature of the dispute and his frank and funny answers ensured that the room was always crowded. Whether or not he already knew it his press conferences were the work of a superb stand-up man. He loved giving them and his quick wit and warm personality meant that he held the press in the hollow of his hand. He gave more of them than any Prime Minister before or since, and more perhaps than he should have. His audience in the room stimulated him to rising flights of wit and irony. Bill Rowling, his ambassador in Washington, told me he came to dread Sunday evenings when reports of Lange’s post-Cabinet press conference came in. Lange was unconcerned; he seemed annoyed that at the height of the anti-nuclear dispute allied governments, and Beijing and Moscow as well, spent time scrutinising every sentence. When he walked from the lectern and said “That went well” he meant the response of the room and not the likely reaction in friendly capitals. When he discussed his foreign visits in later taped reminiscences he liked to rank them by how successful the press conferences had been rather what had been achieved in the talks.[3]

His wit was almost always original and of the moment. It flashed out even in the most ordinary of conversations. A few strokes were perhaps prepared in advance. Once at Heathrow airport he spotted and walked over to a machine that said ‘I speak your weight and fortune’. When he returned he told me it had said ‘One at a time please’. Other good stories he would borrow. I once joined a group to hear him telling as his own my account of the watery burial of Shorty Burnett in Samoa.[4] He was unembarrassed, giving me a cheery wave and then finishing the story.

His diffidence with those in more formidable positions meant that he carried little weight with other heads of government. At the Bahamas Commonwealth meeting he had little to say and, as always when he was nervous, spent time making disparaging remarks to me about the Canadian and other leaders. Bob Hawke, the Australian Prime Minister, positively disliked him and that was not solely because of their differences over ANZUS. Mrs Thatcher put up with him because, as she told Lee, New Zealand was too warmly regarded by the British public to understand a tough response. Lange, though, was even more nervous than usual at meeting her and to win her approval told her that his government would not even seek to enquire into the armament of British naval visitors. It was the exact opposite of our oft-reaffirmed position on American visits and though the British continued to seek more detail the thought was clearly one to get him through the Thatcher meeting and disappeared as soon as it was over.

Prime Minister Nakasone of Japan asked to see him when we were in Delhi for Mrs Gandhi’s funeral, to form a view of this man who might rattle Japan’s rather delicate anti-nuclear stance. The view was clearly unfavourable. Nakasone was haughty, listening with his eyes half closed. At their next meeting in New Zealand he went even further, going to sleep throughout a long car journey with Lange. The American Secretary of State, George Shultz, who saw most of him was even rougher. “Your Prime Minister lied to me” he said to our ambassador and when I talked to him years later he leant across his desk to say, “I formed a very poor impression of your Prime Minister” – a verdict which seemed the most damaging of all.

It is tempting to speculate whether Lange’s lack of self-confidence and desire to appease whoever he was talking to were the result of his upbringing. I always had the vague impression that his childhood was not a happy one. He liked his father, a medical doctor, who was perhaps the person who gave him the right children’s books to read and from whom he learnt his pleasant social manners. The turmoil over the devaluation and change of government turned out to be surprisingly demanding and both Bernard Galvin and I were diagnosed with exhaustion and sent to bed. While lying there looking at the ceiling I received a handwritten letter from the new Prime Minister, apologising for his thoughtlessness in overworking me and wishing a speedy recovery – the only time any Prime Minister ever enquired about my well-being. At the other end of our association he flew down unannounced to my retirement drinks at Parliament Buildings, making a warm speech in which he again apologised, this time for the awkwardness of my cancelled appointment as Secretary of Defence.

His fierce mother, though, does not seem to have liked him much and to have systematically undermined his confidence. When Julie said she must have been pleased when her son became Leader of the Opposition she snapped, “No, why should I be?” Her public comments about him were never favourable, culminating at the time of his divorce with her observation that it was a pity he was ever born.

His mother may have been fonder of Naomi than he was; certainly his family were angry over his divorce and remarriage. Naomi had a sweet nature and a devout Methodism but she did not have David’s education or sharp mind. She was pretty and socially reachable for an overweight boy brought up to be uncertain of himself. Later, as he grew into his potential, the gap between them widened. He was not a ladies’ man but the love his speech-writer, Margaret Pope, had for him was bound to tell in time.

Their affair was thought to have started in London, and if so I was one of the first witnesses. David had arrived for the Oxford Union debate and was staying at the Howard Hotel. I arrived from Ottawa where I had been shoring up our intelligence relationship. I asked the policeman on the floor if the Prime Minister was in and when he nodded knocked on the door. After several knocks returned no answer I left and returned some hours later. This time the PM opened the door and I mentioned that I had tried earlier. He hesitated for a moment and then said he had been walking in the Park. Something about his manner suddenly convinced me that the affair was under way.

He was understandably reserved on this but he was on most burdensome issues, perhaps to save himself the bother of dealing with criticism or disapproval. He hated confrontation and went to considerable lengths to avoid uncomfortable duties, like rebuking or firing people. Wherever possible he passed these duties to someone else and if this was not possible then he avoided the difficulty as long as he could. When he felt nervous the clauses and sub-clauses tended to multiply. Even the jokes and stories could be a way of pacifying people or fending off their demands.

He liked to be thought agreeable, and he was. Another witty and unserious Prime Minister, Disraeli, defined an agreeable person as “someone who agrees with me”. Lange reversed this, trying to agree as much as possible with everyone else. So in daily meetings he was comfortable to work with, a marked difference from his predecessor. He had an endless string of funny stories about his colleagues and many others and my early morning meetings stretched from a brisk brevity under Muldoon to nearly an hour under Lange. We started with a little tussle over names. He wanted me to call him David. I said this would be an honour in private but our working relationship was a professional not a personal one and in public or when working I would call him ‘Prime Minister’ or ‘Sir’. I think he was a little hurt by what he saw as my being standoffish but after a slow start everyone in the office who was not a personal friend followed suit.

The professional barriers took a dent when we kept house together on Funafuti in Tuvalu during a meeting of the Pacific Forum. We moved into an empty expatriate bungalow on the edge of the airstrip which took up most of the little island. As might be imagined Lange was not much of a housekeeper. We took turns at making breakfast but whenever the tea and toast was ready David would have wandered off through the banana palms to talk to someone he had seen, returning to tell me enthusiastically that the aunt of the woman he had been talking to had a shop in Grafton Street.

A bicycle appeared on our porch and at sunrise I wobbled through the village in the cool of the morning. I told David at breakfast and he immediately went to try the bike himself. I discovered later that the Samoan delegation waiting on the airstrip for an RNZAF plane had been startled by the sight of the New Zealand Prime Minister passing them on a bike and waving uncertainly, “Flight’s cancelled. We’re going by bike”.

Despite the uncertainties of breakfast then, food was always of interest to Lange, as his fluctuating size often showed. He did not enjoy dinner parties, not liking to be tied down between two partners and unable to work the room. Receptions gave him more scope and the laugh would boom out as he rolled around the guests, picking up snacks from the passing trays and enjoying the effect of his jokes. When we assembled in Los Angeles to be excommunicated from ANZUS (Lange characteristically called it “a heavy meal”) one of the American delegation, Jon Glassman, said he was struck by Lange’s intense gaze at something on their side of the room which turned out the cakes and cookies laid out in a bookcase for our break. This has passed into mythology, along with the story of Muldoon drunkenly calling an election, but I was sitting beside David and have no memory of the cakes opposite, though my mind was on other things. Some refreshments were certainly provided.

His inexplicable gamble over Fiji could have brought him down but it was a further example of his liking to act alone that actually did so. In April 1989 he made a speech on New Zealand’s foreign policy at Yale University. The speech was carefully written and widely circulated to Ministers and others in Wellington. John Henderson travelled to Washington to tell the Americans that it contained nothing controversial. Lange himself gave an assurance to Cabinet a few days before his departure that he would not raise the future of ANZUS in his speech. So there was considerable surprise when Lange did just that at Yale, declaring it was time for New Zealand to leave the alliance.

The news reached New Zealand on Anzac Day, a particularly unfortunate time when a number of Ministers in commemorative speeches had stressed our continuing commitment to the alliance. The Acting Prime Minister, Geoffrey Palmer, rang me in some heat to ask why I had not shown him this part of the text. I explained that the offending remarks did not appear in any of the copies we had, nor did it appear in the speech copy Lange had with him. David had ad-libbed and it was the end. Even Palmer, the most loyal of deputies, walked away.

There was, inevitably, a last touch of Lange confusion. After Yale he went on to Canada, giving excited press conferences about how he had been misunderstood. One morning he went back to the government guest-house where he was staying to find two or three people with a cameraman in his room. An embarrassed Canadian Government claimed that they were there to take pictures for future alterations but this seemed a bit thin since they would only to have had to wait a day for their guest to be gone. Whatever the truth, it seemed a fitting accompaniment to his untidy time as Prime Minister.

He went off to be an entertainer, which he was good at, but an underlying uneasiness showed in his increasing tendency to sue people who had not spoken well of him. It was expensive and pointless, surprising in a good lawyer who should have known that people in public life must in law as well as in reality accept a sharper level of criticism.

He began to drink. For most of his time in politics his Methodist upbringing meant that he did not drink, or at least I saw no sign of it. Towards the end of his term the gathering strain led to an occasional glass of wine, and someone who had difficulty controlling his liking for food was always going to have trouble with drink. Sitting behind him on an RNZAF aircraft, a steward came round with wine and for the first time I saw Lange’s hand extended for a refill. This was a surprise but not a worry in those last months. If he drank more it was done very discreetly. But there was a tragic period after he left office when he fought his depression with binge drinking and passers-by in Sydney were surprised to see the former Prime Minister of New Zealand sitting glassy-eyed on a park bench.

He enjoyed the excitement of being Prime Minister but the effort was too much. The curse of that office, though, meant that he could not comfortably settle to anything else. Perhaps over the long run he would have been happier managing an insurance company but I doubt it.

[1] Told to me by Air Vice Marshal Klitscher.

[2] Told to me by Russell Marshall, the embarrassed Foreign Minister.

[3] The transcribed tapes of the interviews with Vernon Wright are in the Archives,

[4] See page 19 of my memoir, Final Approaches.